Washington’s Christmas Eve Gift

- Share via

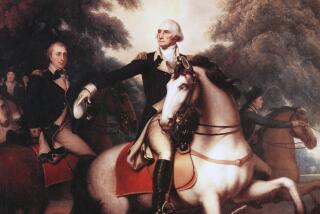

We don’t associate George Washington with Christmas Eve, or Christmas itself, yet the most significant Christmas Eve in American history occurred in 1783, when Gen. Washington, then 52, headed home to Mount Vernon after nine years at war -- and turned his back on ruling the states like a king.

The American Revolution effectively ended at Yorktown in October 1781, but in the fall of 1783 the defeated British still held a few positions as bargaining chips for negotiating the peace. Although a treaty acknowledging American independence had been signed, ships carrying the documents were still at sea when Washington gathered up his remaining troops in November at West Point and headed for New York City, to take over as the last Redcoats embarked for Britain.

Equally important to Washington was his desire to have Christmas dinner with Martha, to bring yuletide gifts to his wife and his step-grandchildren (he had no children of his own) and to return to being “a private citizen on the banks of the Potomac ... under the shadow of my own Vine and my own Fig-tree, free from the bustle of a camp and the busy scenes of public life.”

That his imagery recalled the biblical book of 1 Kings is an irony he may not have recognized. He was renouncing the idea raised by his admiring countrymen -- who had long lived under monarchs, the common form of rule everywhere -- that George III be replaced by their own George I.

“Had he lived in days of idolatry,” a colonist had written in 1777, “he would have been worshiped like a god.” Abigail Adams wrote of Washington’s “Majestik fabrick.” To one poet he was “Our Hero, Guardian, Father, Friend!” To another he was “First of Men.” And, by 1778, a Pennsylvania German almanac had referred to him as “Father of his Country.”

A brigadier general wrote to Washington, echoing sentiments in the press, that the colonies should merge as a monarchy, with him as king. Washington responded: “I must view this with abhorrence and reprehend [it] with severity.”

Philadelphia artist Benjamin West, painting in London on the commission of the king, told George III that despite Washington’s popularity, the general chose to return to his farm in Virginia. The king was astonished. If Washington does that, said His Majesty, he will be the greatest man in the world.

In December 1783, the general made good his word.

Crossing the Hudson from New York on Dec. 4, Washington began his journey home and away from public life. He rode through villages and towns in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland. Americans watched expectantly for his arrival, banquets and balls were planned in his honor along the way. When less formal crowds gathered, he stood atop the wagon carrying his belongings and thanked his countrymen, even those he knew had been less than loyal to the American cause, for supporting the new nation.

At Annapolis, Md., where the weak and disunited Confederation Congress was meeting, Washington planned to showcase his retreat from public duty and public life. He would return the official 1775 parchment appointing him commanding general. The occasion was to be a piece of theater to emphasize the nation’s civil foundations.

The adulation along the way delayed his arrival in Annapolis to Dec. 22. There he penned his parting address for delivery the next afternoon -- the only valedictory he would ever give in person. (The “Farewell Address” of 1796, written largely by Alexander Hamilton to mark the end of his second term as president, was never spoken. It was published in a newspaper.)

On the evening of the 22nd, Washington was honored once more at a banquet and ball, this one punctuated by 13 patriotic toasts and ceremonial salutes by cannon. Late that night, he returned to his lodgings and reviewed his speech. Apparently no longer sure that he would or could bar the door to further public service, he deleted two phrases suggesting finality: “an affectionate and final farewell” and “ultimate leave.”

The address the next day at the Maryland State House was a solemn occassion. “The glory of your virtues will not terminate with your military command,” Thomas Mifflin, president of the Confederation Congress, told Washington, “it will continue to animate [the] remotest ages. You have defended the standard of liberty in this new world.”

Up and down the former colonies, newspapers would report the remarkable events. “Here we must let fall the scene,” the New Hampshire Gazette closed its report. “Few tragidies ever drew more tears.”

It would not be Washington’s final act, as he had hoped -- although with less and less assurance as he neared home. From retirement, he watched the nation drift toward disunity, and then answered the call to lead first the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and then, by unanimous vote of the first electoral college, the republic.

After serving two terms and with the nation now set on course, he would retire, this time for good, from the public stage.

But none of that was known on Dec. 24, 1783, when Washington’s party crossed the Potomac to Virginia. Winter twilight came early. Up the slope from the river, Mount Vernon, with its three shuttered doors in the white west front and its many green-shuttered windows, now candlelit, beckoned.

The next day, as a heavy snowfall locked the plantation in snow and ice, Washington at long last celebrated a festive and unmilitary holiday. There he confronted, he later wrote, just one challenge: an “Attack of Christmas Pyes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.