A Chess Champion and His Demons: Still Searching for Bobby Fischer

- Share via

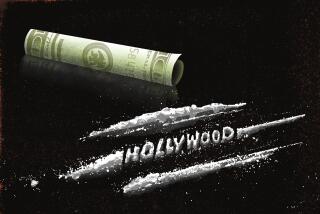

I recall a crisp, terribly exciting fall afternoon in 1992 in the southwest corner of Washington Square Park when the normal habitues of the chess tables -- Manhattan’s drug dealers, hustlers and impoverished masters -- had been replaced by Hollywood stars.

They were making a movie of my book, “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” and on this day they were shooting scenes at the same tables that I had so ecstatically and tremulously visited hundreds of times with my little boy, Josh, when he was first learning the game and taking on all comers. Some of his fans called Josh “Young Fischer,” after the great chess champion who had himself played some of his early games on the same grungy tables.

During that time in my life, the game of chess possessed me like an utterly captivating and dangerous love. I had been intrigued with chess ever since Fischer turned the world on edge with his match against Boris Spassky in 1972, and then years later I was set on fire by my son, who turned out to be a chess prodigy.

I wanted my son to be a chess champion like Fischer, and at 15, Josh was a six-time national chess champion. If ever there was a moment when immortality seemed to be breaking my way, it was on that sweet afternoon in Washington Square with the cameras rolling.

But I was concerned about one thing in the shooting script. Fischer was depicted, only half-truthfully, as a boyishly handsome, charismatic charmer who became a cultural icon after winning the world championship. In fact, when I was doing research for my book I had discovered, sadly, that the beauty of Fischer’s chess constructions was not mirrored in his personal life. Friends described him as tyrannical, deeply paranoid and a fervent hater of Jews. Shouldn’t some of that, I wondered, come into the movie?

Steven Zaillian, the director, brushed me off and portrayed Fischer as a demigod. And no doubt, he made the right call. After all, how could he have made a convincing movie about a brilliant, warmhearted boy whose role model loved Hitler and would later tell the world he was ecstatic about 9/11?

Movies, even great ones, often opt for mythology over verisimilitude, which is fine, but the question continues to intrigue me, particularly given the sad story of Fischer’s arrest in Japan earlier this month and his likely deportation to the United States: Who is Bobby Fischer?

Born in Chicago and raised in Brooklyn, he was arguably the greatest player in the history of chess. He was an immensely gifted prodigy who first won the U.S. national championship at 14. In the summer of 1972, at the height of the Cold War, Fischer’s struggle for the world title against Russian champion Spassky -- fought in five-hour battles of abstruse and dazzling complexity -- filled millions of Americans with a passion for the game.

Fischer won but, surprisingly, refused to defend his title in the years that followed, turning down innumerable financial offers and disappearing from public view. For nearly two decades he lived in cheap rooms and walked the streets of Los Angeles in disguises. His fans wondered if he still played and if he was still great; a mythology grew about the hermit chess genius who might be growing stronger and stronger by the day.

Then in 1992 Fischer surfaced for an exhibition match against Spassky for $3 million in Serbia, violating the U.S. embargo against the government of Slobodan Milosevic. Later, in exile from the U.S., his profane public rants against Jews caused distress to even his most ardent fans. But Fischer’s dream, my son reminds me today, was not social iconography, but rather chessic works of art that would stand the test of time. Genius players live in a kind of parallel universe. They don’t see chess the way we do. The language of the game, the complex openings, strategies and astonishingly deep calculations become like a heartbeat. The high math that most of us would find daunting leads them to an inner music, my son says, or perhaps something even more abstract, like the very flow of creation that they feel in their hands as they move the pieces.

Chess is often spoken about as a metaphor for life, and for great players it is the purest way to express themselves. For the greatest of the great, such as Fischer, the outside life becomes secondary to chess. Such players become immersed as if they were living under the sea. But then sometimes they surface, with wild strokes, an iconoclastic thrashing, as if the real world, as we know it, seems threatening and even a little insane.

Here is a little story that might shed some light. Ten years ago I was riding in a car with my son, a lovely girl and a brilliant grandmaster who had just completed a masterpiece game a few minutes earlier. The grandmaster was playing through the moves in his head. My son and the girl were beginning to flirt and their youthful pleasure was refreshing and hard to ignore. When the grandmaster noticed he turned away and began to sing. His singing was inappropriate and lurid. He sang louder and louder to drown out this intrusion.

My son no longer plays chess. It was a thrilling and memorable part of his life, but he is surely happier today, writing, teaching and competing as a martial artist. As for myself, I have written only six pages on chess in the last 10 years. Even writing this column makes me sweat and yearn for more. I know I have to stay away from the game or it will have me again.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.