Hang Time

- Share via

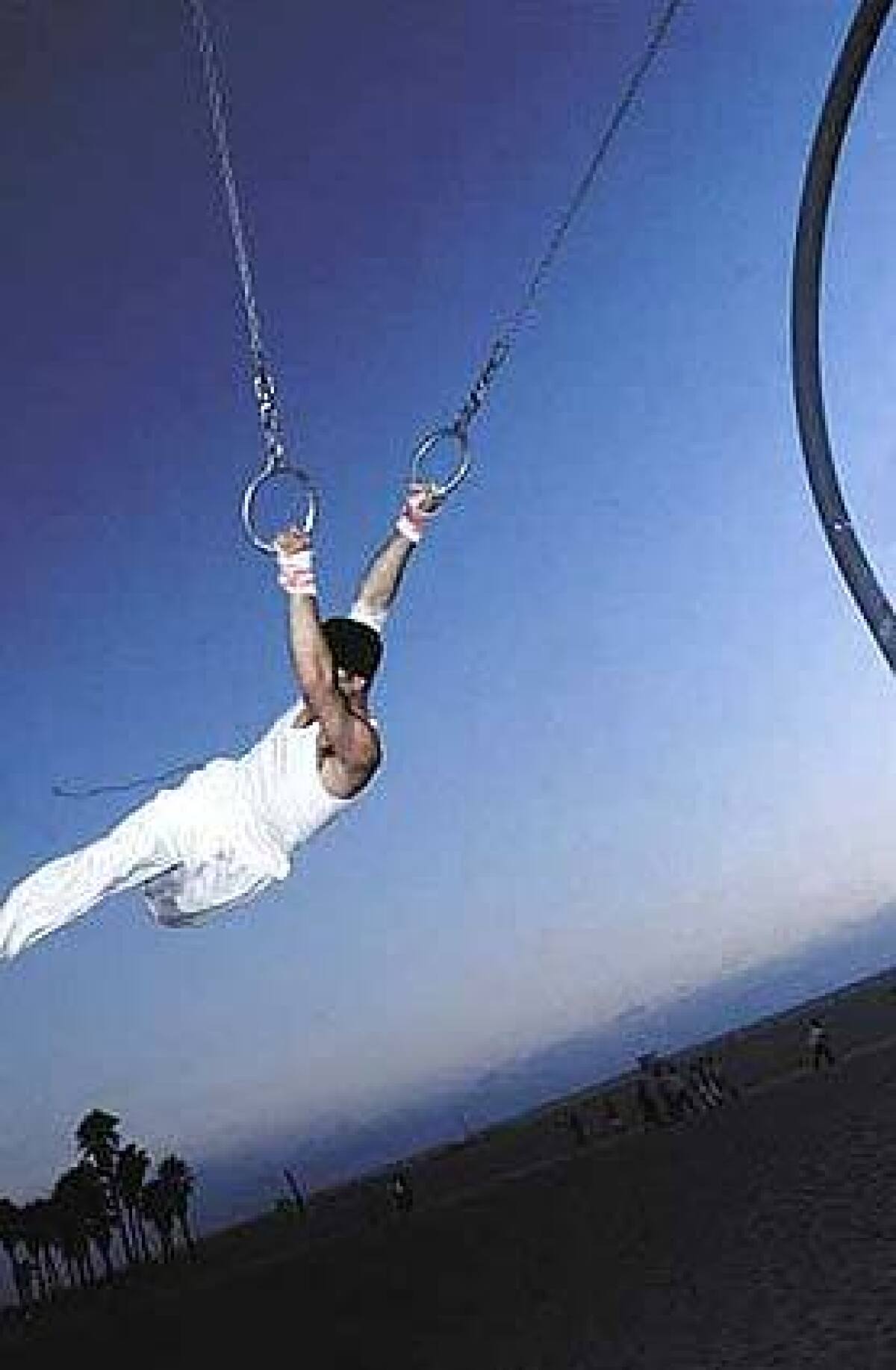

“Filchyboy” is in the zone. He reaches up, grabs the first ring and solemnly lowers his head, then begins running back and forth to build momentum. He takes off and kicks his feet, toes pointed, out to one side. His face tilts back to greet the sun. He grabs the second ring with his free hand and pushes himself higher by cranking downward with his ropy arms. For a split-moment he makes contact with a supporting pole and alights there, Spider-Man style. Then he swooshes down, chest forward, arm outstretched for the next ring, and the next, down to the 10th ring and back, along the way completing a series of twirls, flips, dislocates and then, finally, a daredevil dismount into the sand.

His return to earth is met with claps, compliments. “Great, man.” “Nice swivel.” Filchyboy pulls off his headphones, grins, and is absorbed into the cluster of swingers waiting their turns.

Most of them are regulars: about two dozen young men and a few women, many in their 20s and 30s, who come down every weekend to work out on the traveling rings on the beach just south of the Santa Monica Pier. More than just a pastime, the rings are a significant fixture in their lives. They’ve helped some pull themselves together after debilitating setbacks, both physical and emotional. They’ve provided a focus and a community. Many swingers liken the scene to an ad hoc family.

Yet at the same time there’s a loose, unmoored quality to the group. Most don’t know each other’s last names—many, like Filchyboy (Chris Filkins), go by nicknames—and as for where anyone’s from and what anyone does for a living, who cares? At the rings, what matters is what you can do 15 feet up in the air.

To be clear, the ring swingers don’t swing. Rather, they fly, soar, kick, coil, twirl. Tourists and other beach-goers regularly gather around, agape at the complicated routines and tricks—moves that resemble maneuvers from X Games sports such as skateboarding and snowboarding, or a D.I.Y. version of Cirque du Soleil.

“It’s not like traditional gymnastics. It’s more street,” says Robert Chapin, a professional stunt- and swordsman who trains at the rings. (Last summer, when the swingers recruited former U.S. Olympic gymnastics judge Frank Endo to judge their annual self-organized competition, some were disgruntled when he deducted points for toes that weren’t gracefully pointed.)

Beyond the swingers’ skill and daring, the sheer scale of the traveling rings, which until recently were the only set of their kind in the world, commands attention. The 75-foot-long, 15-foot-high steel frame supports 10 rings, each set about 8 feet apart and suspended 7 feet off the ground. The idea is to swing down and back as artfully, and inventively, as possible, ideally without hitting a pole or rogue ring. Or worse. Four years ago, Paul Scott, a rings elder at 52, fractured a vertebra while practicing a back flip.

There’s no real glory in the rings. No money. No sponsorships. Impressed hoots from tourists are about it. But for the regulars, the rings serve intense, almost religious roles in their lives.

“Everyone gets sucked down here for different reasons,” says Wil Bethel, a writer who waits tables and who bicycles to the beach from Koreatown twice a week.

For Filkins, a 39-year-old single father, the rings were a kind of salvation when his life was at a low point a few years ago. His wife had run away, taking their daughter with her. Filkins, who’d been a stay-at-home dad, was without a job and spent six weeks living on the beach, showering with the homeless, his world reeling. Eventually he picked up the pieces: got hired at a website, gained custody of his daughter, moved into an apartment in Santa Monica. He also bought a pair of roller blades, which led him to the rings, where he’d watch a dreadlocked swinger called “Action” fly through the sky.

“After about a year or so of that I finally started trying it myself,” Filkins says, propped up on a low wall near the rings. The wall separates the beach from the Rest of the World—the clots of tourists tooling along the bike path and the chi-chi hotels.

“It gave me all of my self-esteem back. I feel like I’m a completely different person than I used to be a few years ago,” he says. “I don’t know whether it would have happened without [the rings], but this definitely gave me focus.”

Now he and his 11-year-old daughter, Kassia, are both regulars.

It’s a warmer-than-usual Sunday in May, and Jessica Cail and Brad Meyers are starting to heat things up. They’re practicing double leg-overs, a trick that involves swinging a leg over a ring and, in the process, momentarily letting go of the ring to reach under and grab it again, then doing the same with the other leg. In execution, it looks something like airborne leapfrog.

Cail, with long red hair pulled back in a ponytail and a sturdy build, drops from the third ring. “I miss on the left, still,” she says.

Meyers falls to his knees in the sand and sits back on his heels, prayer-like, to stretch his quads.

Gena Sorochkin, bearded and unseasonably dressed in winter biking gear, sits on the wall and watches. Scattered around him are bags of white hand chalk, tossed sweatshirts and water bottles.

While growing up in the Soviet Union, Sorochkin was a cyclist on the junior national team. “When I was 7, I wanted to do gymnastics, but I was told I was too old,” he says. “You have to start when you’re 4, 5. Now I’m 44 and doing the rings . I’m older and I take long breaks, but at the end of the day I still have my hands.”

Sorochkin turns over his palms: They are only slightly roughed up with calluses.

A new arrival, Erick Cabrera, drops his gym bag onto the sand. “The sun’s not too strong,” he says approvingly.

Cabrera is greeted with an outstretched fist by Michael Villegas, a soft-spoken machinist who wears wire-rimmed glasses and his dark hair pulled back in a braid.

“Hey, man,” Cabrera says as their fists touch. His crooked grin reveals a chipped tooth, courtesy of a wayward ring.

Fists are the secret handshake of the rings fraternity. Besides connoting insiderdom, they’re also practical. Swingers have heavily callused and sometimes bloody hands. Fists keep it clean and painless.

Cabrera rides his motorcycle to the rings from his apartment in Hollywood every weekend, sometimes after nights working as an exotic dancer. By day he’s a personal trainer and bodybuilder, and his swollen pectoral muscles twitch slightly as he talks. (Like most of the male swingers, Cabrera generally forgoes a shirt.)

For him, the rings are “like flying.”

“There’s no equipment. Only your grips and your talent,” he says. “When you’ve got a problem and you come here, you forget about everything. It’s like doing yoga. I don’t do yoga, because I know I can find a better source when I’m feeling bad. I come by here, and it’s only my soul and my security.”

Seven years ago Cabrera was working as an electrician in Mexico City and was nearly killed while fixing an elevator. Unable to get out of the shaft, he was forced to fall seven flights to avoid being crushed when the cab above him began to descend. He shattered his knee and was unable to walk for eight months.

When he recovered he felt “born again.” He started taking his life, and his body, more seriously—lifting weights and, three years ago, training on the rings. (Not that he lives entirely risk-free; since the elevator trauma, he’s survived major motorcycle and skydiving accidents and has the scars to prove it.)

Today, Cabrera says, “I feel great, man. I feel great with my life, with God, you know. He gave me a lot of opportunities.”

There are a few unwritten rules at the rings. Such as: chalk is to be shared. A swinger gets only one warning when he’s about to be hit by a ring (the rings can swing violently when a swinger pushes off from one to the next). But most important: Nothing matters more than style.

“Everybody tries to raise the level and tries to come up with new tricks, which is cool,” says Bruno Angelico, a French Italian ringsman. As he talks he applies a mixture of Chinese herbs to his sore upper arms—preparation for his first swing of the afternoon.

“I’m kind of farouche. An enemy of routine,” Angelico continues in his thickly accented English. “So every time I come up with something I like to raise the stakes higher. For me this is not about working out. It’s also about being able to create.”

Three years ago Angelico’s back was broken in a car accident, and only recently has he been able to return to the rings.

“When I was at the hospital the only question I had to the surgeons was, ‘OK, but when you think I’m going to be able to go back on the rings?’ ” he says. “They would look at me and they go, ‘Bruno, we’re just trying to get you walking.’ The first time that I grabbed the rings again, I was like, was I doing this stuff before? It was like moving walls. It was so hard.”

Now Angelico is trying to get back to the point where he can swing upside down, a move enabled by a metal hook he Velcros around one ankle.

Angelico isn’t the only one with a signature trick. Filkins is known for his pole play (the Spider-Man move). Chris Tin, a.k.a. “Flyaway Chris,” a film composer with a mop of straight black hair, is so nicknamed for his dismount, which incorporates a soaring back flip. Cabrera likes to roll upside down and swing with both hands and feet on the rings, inspiring monkey-calls from his friends.

“Just walking down the beach at night, you can tell who it is by their silhouette,” says Jessica Cail.

The first public gymnast rings in Santa Monica were built in the 1930s for the original Muscle Beach. Back then there were several sets, some with only a pair of rings. Ross Simms, now 70, a Muscle Beach alumnus who performed on them in the late 1940s and early 1950s, is crankily dismissive of the current generation of beach swingers. “They’re not doing the same tricks I was doing,” he says. “Those guys are just swinging on rings. I can do what they do all day long.”

In the late 1950s, the Muscle Beach equipment was dismantled. Soon after, a set of 10 traveling rings was designed by a local architect and built by L.A. Steelcraft, a Pasadena-based recreation equipment company. They eventually fell into disrepair and were often missing rings until the late 1980s, when a group of Muscle Beach old-timers pushed to have the area restored. Although there was initial resistance from the city of Santa Monica, which feared liabilities, the current set—also built by L.A. Steelcraft—was installed in 2000, along with a smaller set for kids.

Two years ago, Dorlene Kaplan, a publisher of guides to educational travel and self-described “rings enthusiast” who lives in New York City, worked with the city’s parks department to have a set of traveling rings erected in Riverside Park on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. In May, Kaplan got approval to build a kids’ set. She’s also trying to bring the rings to Miami Beach, where she grew up.

The New York rings inspire more of a “family-type thing” than the Santa Monica rings, Kaplan says in a telephone conversation. “It’s really quite different in terms of the people who use them. There are some hotshots who come out, but on the weekends I usually see families.”

“Eyes open, iPods down!” Filkins barks. It’s nearing dusk and the shadows of the rings are starting to get long, the hazy yellow sun more forgiving.

Filkins and four other guys are working on the Switch, a difficult routine in which people swing one after the other and form a human chain, then bypass one another (that’s the tough part) when they turn to head back. Filkins, Cabrera, Tin, Meyers and Eddie Saleh have been attempting the move for a few weeks but have yet to nail it, even after practicing on the kids’ rings and discussing it on https://www.Swingaring.com , a rings-dedicated website where swingers chat and post messages (“Grips for sale!”; “Anyone heading down today?”).

“Last night I was thinking about the move and some possibilities,” began a post by “Venice.” “If we do something quickly after we clump up it will work, but the pull in the middle is intense if we hold it.”

Filchyboy responded: “I think Chris was right yesterday. On the smaller rings the pull in the middle shouldn’t be so bad and we should have more time to work out a move before our shoulders fail from the stress. I think some cool stuff may come of this.”

On the beach, these theories get broken down into simple edicts. “Swing real big!” Filkins calls as he sets out. The others follow until a chain is formed and everyone is sharing a ring. Five pairs of feet dangle above the sand as an audience of beach-goers, en route to their cars, begins forming, sensing something’s up. So far so good.

Things fall apart when it’s time to switch directions. Saleh, unable to maneuver past Meyers, is forced to drop to the ground. The rest of the chain quickly collapses.

“Hey, you weren’t supposed to let go,” Cabrera kids Saleh as the men regroup in huddle mode.

“We had the timing down, we just need to apply that when we get bigger,” says Tin, who has the strategic mind-set of an Eagle Scout. Last year he had “Original Muscle Beach Traveling Rings” T-shirts made and helped organize fundraisers for Sept. 11 and tsunami victims.

“I wasn’t pulling high,” someone confesses.

“Let’s see if we can do four. We did five last time,” suggests Filkins.

No one argues. But after a few better-but-still-not-there attempts, the Switch is abandoned for free form.

Filkins puts his headphones back on and walks a few yards away from the others. He rests his hands on his hips and looks out at the ocean. The water is placid under the crazily lit sky—pink- and orange-streaked, with purply-blue clouds.

It’s time to fly.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.