With World War II Memoir, a Literary Legacy Continues

- Share via

BOSTON — The young man scribbled in secret, knowing that Navy policy barred sailors from keeping diaries. Writing had always been important in his family, and so for three years, Michael James surreptitiously recorded his impressions of life aboard a World War II aircraft carrier.

“Had one hell of a time finding my sack, below three others, which is in forward end of the ship,” he wrote Sept. 15, 1943, his first day aboard the Monterey. “They call it the bow. Turns out it was aft.”

James, 19 at the time and a scion of one of America’s most famous intellectual families, was so disoriented after boarding the ship at Cape May, N.J., that he never did locate his assigned bunk that night. Instead he found “lots of empties and lots of noises, too.... Chatter, snoring and air pumps.”

Along with photographs and news clippings, the handwritten chronicle remained tucked away until this year, when a nephew persuaded James to let him publish the wartime memoir. “The Adventures of M. James” takes its place beside the philosophical ruminations of James’ grandfather, William James, and the novels of his great-uncle, Henry James.

At 82, the latest author in the James clan said he was not moved by literary ambitions when he started his wartime journal. But since childhood, he had meticulously saved letters, pictures and documents.

“I think everything is history,” he said. “So I started writing the moment I boarded that ship. I wrote no matter how miserable the conditions were. I was lonely, innocent and scared. I had never been on a ship before. I knew nothing. And I was 19 years old.”

After the war, Michael James found his future as an artist, supporting himself along the way as a roughneck in the Oklahoma oil fields and as a sewer worker around Boston, where he has lived for many years.

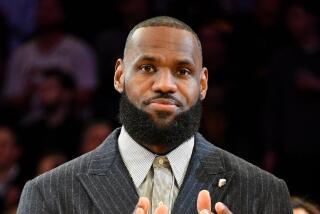

The book’s cover depicts James as a skinny young sailor with baby-smooth cheeks. He grew a rakish mustache in the Navy, but today wears a Lincolnesque beard that, like his full head of hair, is snowy white.

He makes a habit most days of taking a vigorous stroll along the Charles River. But on a recent rainy day, he stayed in to enjoy a hearty fire in his flat in the Back Bay district. Joined by his nephew, Henry James, he reflected on the nature of war and the burdens and privileges of intellectual lineage.

Michael James was studying art in Colorado when the war broke out. To support himself, he flipped burgers at a joint called Wimpy’s. About a year into the conflict, a soldier from Ft. Carson stuck his head in the window counter, ordered a Wimpy burger and with a heavy dose of vitriol asked James: “How’s the war going?”

James remembers how the words stung. “It was like a knife going right into my conscience,” he said. “I went home and enlisted because of that.”

He chose the Navy because he thought the Army would mean sleeping in ditches. “In the Navy, I knew I would have a clean bunk,” he said. His two older brothers also had joined the war effort, one enlisting in the Marine Corps and the other in the merchant marine.

James entered the Navy as an apprentice seaman, a low rank. He left a petty officer first class.

As a Pacific fleet commander, Adm. John McCain, whose grandson would become the U.S. senator from Arizona, made it clear that no one was allowed to keep journals.

But James found a secret hiding spot, in a locked security box behind the ship’s weather codes. Many shipmates knew what he was up to, but said nothing to superiors.

Immediately after a battle, James often would write his reflections on the events.

“Yesterday, Okinawa was hit, that island off southern Japan, and we did a great job,” he wrote Oct. 11, 1944. “Sank one big cruiser, a smaller one, a can and damaged some other ships. In the p.m. there was nothing left to sink.”

Some days, his entries focused on how many men had fallen overboard in the last 24 hours. “So solitary a death,” James observed. He described a man who lost his head at the shoulders. “Well,” James commented, “where else?” And day after day, he expressed concerns for his beloved brothers -- who both survived the war.

Although he was raised in a pacifist family, the patriotic pull of what he now calls “a clean war, a good war and the right war” overwhelmed any reservations James might have had about fighting and killing. His diary depicts an unexpected eagerness.

“I was feeling the moment in the extreme,” he said as he added another log to the fire, then took his seat next to a large easel where he paints portraits and landscapes. His artwork, as well as his father’s, covers almost every surface of the Victorian-era apartment.

“I would run in from kamikazes falling around and write because the moment was there,” he said. “It was adrenaline, intellectual adrenaline -- but also, physical adrenaline.”

But James was perplexed by his reaction. “I had been a pacifist,” he said. “And this is what I don’t understand: I enjoyed the action.”

University of New Mexico philosophy professor Russell B. Goodman, an expert on William James, said this emotional paradox had a familiar ring.

“I am struck by the resemblances to his grandfather,” Goodman said.

William James painted until he was 17, Goodman said. The philosopher-physician who is credited with inventing the study of pragmatism harbored a mischievous streak, much like the defiance Michael James exhibited by skirting Navy policy to keep his journal, the professor noted.

Michael James put together a typewritten manuscript of his diary in the 1980s, the younger Henry James said. A New York publisher turned it down, saying it lacked character development, so the manuscript languished until Henry convinced his uncle that his story should be told. The nephew launched a desktop publishing venture, Turn of the Screw Press, for the project. Just 2,500 copies were printed.

“In a sense, this is a real continuation of the James literary legacy,” said Roberta Sheehan, a William James scholar who recently completed a compendium of the philosopher’s letters for the University of Virginia.

“You had 2,500 guys out there on a big boat, and one of them committed the experience to writing,” Sheehan said. “He did it, and he did it well. This is a wonderful document, very precious in many ways.”

Sheehan called the book “very reflective, existential at times. Other times, it is an insight into the day-to-day life of a sailor. Some of it is boring, some of it is trite, some of it is sobering.”

Michael James said it never crossed his mind that he would carry on the family’s literary tradition. James, who has battled dyslexia, flunked out of a series of schools, and never thought of himself as an intellectual. A flirtation with fame came in 1951 when he was featured in Life magazine for creating religious-themed sculptures made from junk found around his family’s New Hampshire farm.

“Uncle Micky was oblivious to the aristocracy of the intellect,” his nephew said.

“Not really,” the uncle interjected. “But the richness of it all is behind us. We haven’t done anything since [the novelist] Henry’s death, other than do the best we can as human beings.”

Michael James said he was all too aware that the number of World War II veterans was dwindling.

But he said his wartime journal was less a monument to a disappearing generation than to “the disappearance of me. Because of this diary, I can now die with my head up. I sense the end of my life ahead. But I sense the end of an interesting life.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.