Confessions of a Saudi Militant in Iraq

- Share via

BAGHDAD — “Please, please,” the young Saudi appeals in a whisper, “don’t turn me over to the Americans.”

His face is charred and blistered. His head and arms are enveloped in gauze.

Each word seems to beget pain. His haunted eyes dart about, his only noticeable movements.

He is here to repent, under the stern guidance of an Iraqi intelligence agent. The setting is an anonymous office in the heavily barricaded Iraqi Interior Ministry.

So what does he think now of “Sheik” Osama bin Laden, the interrogator asks?

“He kills Muslims,” the Saudi murmurs, his lips barely moving.

And Abu Musab Zarqawi?

“If they are all like this,” he says of the Jordanian militant, “I want to take revenge on all of them.”

So proceeds the extraordinary televised confession of Ahmed Abdullah Abdul-Rahman Alshai, a 20-year-old high school dropout from Saudi Arabia and one of many young volunteers from across the Arab world who have come to Iraq to wage jihad, or holy war.

Some fight alongside Iraqi insurgents in Ramadi, Fallouja and Mosul, ambushing U.S. patrols, setting off roadside bombs and targeting Iraqi forces working with the Americans.

But the most committed are reserved for suicide missions, a crucial weapon in the insurgents’ arsenal.

The bombers are recruited in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia and in some cases, the back streets of Muslim immigrant enclaves in Paris and other European cities. They are typically blown to bits.

Sometimes, their voices and grainy images emerge posthumously, boasting of their coming attacks on videotaped proclamations that are hawked on black-market CDs. Each proclaims a desire to become a shaheed, or martyr.

But Alshai, though gravely injured, survived the thunderous Christmas Eve explosion he set off in Baghdad’s upscale Mansour district. His rigged gas tanker erupted into a massive fireball at the concrete barriers of a fortified compound housing three embassies, lighting up the night sky. It was a substantial blast even by the standards of this violence-plagued capital.

A dozen people lost their lives that night, including a family of seven Iraqis in one house and a Sudanese guard posted outside the Libyan Embassy down the street. The target may have been the nearby Jordanian Embassy, but it escaped serious damage.

Nor were any U.S. troops in the vicinity, though the oft-stated goal of jihadis like Alshai is to kill Americans.

He is not the first would-be suicide bomber to be captured and debriefed, but seldom has so much detail been made public. The Saudi is among several insurgents whose interrogations are being aired on Iraqi television.

They make similar assertions: They were misled and manipulated and regret their homicidal actions.

Alshai contends that he didn’t know the tanker was going to blow up -- an unlikely story considering that he came to Iraq to fight a jihad against the U.S. and, authorities say, was trained here to drive the difficult-to-handle tanker truck.

Indeed, it is easy to question the sincerity of the confessions and remorse expressed in the government propaganda videos, which began airing on state and private TV outlets in the weeks before the national election on Jan. 30.

It’s clear that many captured insurgents have told investigators what they want to hear, and they may have been coached or coerced.

At the same time, authorities say the information gleaned from interrogations has been helpful in breaking up insurgent cells.

In the case of Alshai, officials say, the debriefing helped lead to the arrest of several top aides of Zarqawi, whom Bin Laden recently designated as his “emir” or commander in Iraq.

Alshai also said police in the former rebel stronghold of Fallouja detained Zarqawi, Iraq’s most wanted man, for seven hours at some point before the U.S. assault in November. But Zarqawi was released, whether through police complicity or incompetence remains unclear.

Alshai’s confession traces his journey along the jihadi trail: from his hometown of Buraydah, known even within Saudi Arabia for its ultra-conservative style of Islam; to his arrival in Iraq through the porous Syrian border with the help of a smuggler; to his placement in a cell in the insurgent stronghold of Ramadi and finally to the truck explosion in Baghdad.

“He pleaded with me not to hand him over to the Americans,” said Brig. Gen. Hussein Ali Kamal, the deputy interior minister, who conducted the interrogation.

As a former Kurdish security official, Kamal has questioned dozens of militants.

“I told him to tell me everything and I will not hand you over,” Kamal said in an interview in the seventh-floor office where he had questioned Alshai. Blood stains were evident in the carpet.

During the session, Kamal said, Alshai provided his telephone number in Saudi Arabia and the Iraqi interrogator called the father, who was astonished to hear that his son was alive.

Earlier, the father had received an anonymous phone call informing him that his son had become a shaheed in Iraq. A letter written in his son’s hand would arrive shortly, the caller told him, Saudi media reported.

The father, a Saudi government employee, had begun receiving condolences in the Arab tradition. He later recognized his heavily bandaged son when Al Arabiya, an Arabic-language satellite channel, ran a clip of the interrogation video.

Alshai, like other militants, appears to have been an aimless, disenchanted young man from a middle-class family who drifted to religious extremism.

It is a common profile among the current generation of holy warriors, including some of the 15 Saudis who participated in the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States.

Alshai’s father told a Saudi newspaper that his son was very calm and quiet in his early years; he blamed clerics for brainwashing his son.

During his interrogation, Alshai said he flew to Damascus at the end of Ramadan, in late October, and crossed the border into Iraq using his own passport with the help of a smuggler.

Once there, he said, he was met by men who identified themselves as operatives of Jamaat al Tawhid wal Jihad, as Zarqawi’s faction was formerly known. The group now goes by the more ornate name of Al Qaeda Organization in the Land of the Two Rivers, a reference to Iraq, where the Tigris and Euphrates converge.

The group is part of an extensive network of religious extremists and loyalists of toppled President Saddam Hussein, among others, who have capitalized on the fervor and idealism of young volunteers, authorities say.

Alshai said he underwent a month of training and indoctrination in Sunni-dominated western Iraq with other jihadis, who included Iraqis, Tunisians, Libyans, Yemenis, Syrians and a Macedonian.

“They come to Iraq to fight and die,” said Corentin Fleury, a young French photographer who spent time with insurgents in Fallouja before the U.S. invasion in November. “They wanted to die. Most of them didn’t know how to fight.”

U.S. commanders say no more than 1,000 foreign fighters are in Iraq, a tenth or less of the entire insurgent force. They play a key role, providing most of the manpower for the suicide attacks, though U.S. commanders acknowledge that accelerating religious militancy in Iraq has produced a crop of home-grown suicide bombers.

Alshai said he arrived in Iraq with $1,800 in his pocket. But his superiors relieved him of his cash and informed him he would be given $100 whenever he asked.

He said he was eventually transferred to an insurgent cell in the southern Baghdad neighborhood of Doura, a rebel stronghold known for its smokestacks and power station, a frequent target of saboteurs. He was trained to handle a tanker truck.

On the night of the explosion, he said, he was instructed to drive the gas tanker to the Mansour district and approach a set of the ubiquitous concrete barriers dotting the city.

“They told me to stop there and to wait for the people who will take the tanker from me,” Alshai told his interrogator. “I stopped and it exploded with me.”

Alshai was thrown from the cab and was rushed to the hospital with others wounded in the attack. Many, like him, had burns on much of their bodies.

He was registered under a false name that appeared to be Iraqi and his role in the attack was not immediately clear. However, Iraqi authorities learned that someone, presumably one of his confederates, had offered a guard at the hospital $50,000 to remove him from the facility. Iraqi intelligence officers swooped in and spirited Alshai away. He was soon in Kamal’s office, telling his tale of jihad from behind a mask of gauze.

On the streets of Mansour, shards of the tanker truck remain scattered in a vacant lot, not far from the shattered residence of laborer Muhsin Sharrad, his wife, Latifa Abdul-Ridha, and their five children. In the blast, their brick and cement home collapsed on top of them. A black banner out front pays homage to the seven Iraqi “martyrs” who perished in Alshai’s attack on America.

“This is not jihad,” said Ayub Ahmad Ibrahim, a 40-year-old Sudanese guard at the nearby Libyan Embassy whose countryman and friend, Essa bil-Naga Ahmad, also an embassy guard, was fatally injured in the blast. Ibrahim showed a visitor snapshots of Ahmad, who was struck by flaming shrapnel from the truck. He died after four days in a hospital.

“This was a cowardly act,” Ibrahim said. “Look what he has done. He killed innocent people. No American soldier was killed. Only poor Iraqis and guards. This is not jihad.”

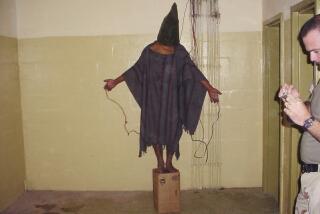

Today, Alshai’s worst fears are realized: He is alive, and sits in Abu Ghraib, the notorious U.S. lockup west of Baghdad. He is one of more than 8,000 U.S. prisoners in Iraq dubbed security risks in a war that U.S. officials once dismissed as being waged by no more than 5,000 “dead-enders.”

A top U.S. diplomat here conceded this month that the insurgency was likely to drag on for years.

Alshai received medical treatment and is recuperating from his injuries.

He won’t be getting out anytime soon.

*

Times staff writers Alissa J. Rubin in Baghdad, Megan K. Stack in Cairo, and special correspondents Said Rifai, Caesar Ahmed and Saif Rasheed in Baghdad contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.