Education of a ‘sane militant’

- Share via

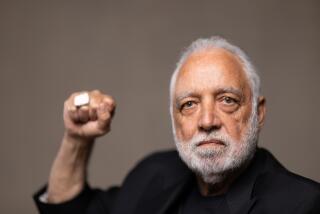

John W. Mack came of age in the Jim Crow South, and he was on the front lines of the battle to break down the walls of discrimination.

“He is part of the Martin Luther King Jr. generation, a generation that did more to lift the banner of ... democracy ... than any other generation,” civil rights veteran the Rev. James M. Lawson said recently during a crowded tribute for Mack on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall. Mack, a pioneer in the student civil rights movement, worked with King in Atlanta. The color line dictated Mack’s young life while he was growing up in Darlington, S.C.

“There were some of these obvious symbols of separation,” he says, recalling “a greasy-spoon hot-dog stand” at the railroad tracks, the dividing line between the white and black parts of town.

“White people could go in and sit on the stools and order their hot dogs,” he says. “We had to order our hot dogs through a window right by the railroad tracks.”

At the only theater in town, Mack remembers, “we could only go to the movies on Saturdays and we had to sit in the balcony. Upstairs. One day.”

He grew up attending segregated black schools and enrolled in North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University in 1954. During his sophomore year, Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Ala. -- catapulting a young minister, King, to national prominence. In that same year, the Federal Interstate Commerce Commission banned segregation on interstate buses.

Mack reacted.

Despite hostile stares from whites, he says, “I rode the Greyhound bus between Darlington and Greensboro, N.C. I would make a point of not sitting in the back of the bus.”

He got his introduction to civil rights organizations when a field director for the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People came to the college. Mack became one of the charter members of an NAACP campus group. He also participated in his first protest against racial discrimination.

“A new dormitory was being built on our campus,” he says. A white construction company put up temporary outhouses, marked White Only and Colored Only, at a historically black state university, among the few public places in the South at that time where African Americans could escape the omnipresent racial restrictions. In response, Mack and several of his schoolmates torched them.

In graduate school at Atlanta University, Mack co-founded the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights along with other students, including future movement notables Julian Bond, a student at Morehouse College, and Marian Wright Edelman at Spelman College.

And he led student protests, sit-ins and demonstrations -- often against the wishes of the more conservative old guard like the NAACP’s executive director Roy Wilkins, who encouraged the young adults to refrain from direct action and allow the legal system to work.

“My Atlanta experience was the defining period for me in so many ways,” Mack says of the period from 1958 to ’60.

King’s and Mack’s mentor, Whitney M. Young Jr., then dean of the Atlanta University School of Social Work, taught the students to be smart and pragmatic rather than angry.

“There were actually nonviolent training sessions, so we would develop a discipline,” Mack explains. “Because when we would get out there on the protest line, the picket line, we had members of the Klan threatening to kill us, calling us every name but a child of God, hitting on us.”

As Mack completed his master’s degree in social work, he received an interesting proposition from Young, who was also moving on from Atlanta.

After a year at Harvard, Young would become head of the National Urban League. He wanted his protege to work for the organization.

“I was flattered,” Mack says, “but frankly I didn’t know if the Urban League was ready for me.”

He stayed in touch with Young, who persuaded Mack in 1964 to work for the league’s affiliate in Flint, Mich. Five years later, Mack moved to Los Angeles. In his first press conference as head of the L.A. Urban League, he described himself as a “sane militant.”

-- Gayle Pollard-Terry

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.