Do penguin brides get cold feet?

- Share via

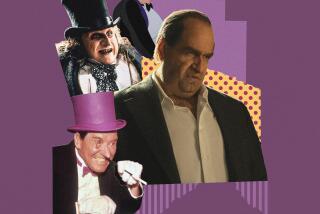

BACK WHEN THE ABILITY to analyze mastodon behavior was vital to putting dinner on the table, humans saw animals in unequivocal us-versus-them terms. Now that we need animals to outdo Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt at the box office, all that has changed. The wild celebrities in the documentaries “March of the

Penguins” and “Grizzly Man” find themselves shamelessly anthropomorphized and romanticized.

Moviegoers flocked this summer -- like lemmings, one could say, or maybe like penguins in heat -- to see the true story of emperor penguins waddling 70 miles across frozen wastes from sea to Antarctic interior to lay their eggs, then heading back again for lunch. Narrator Morgan Freeman describes this as a “love story.” It’s true that, like humans, emperor penguins have monogamous relationships, and as can be the case with humans, they don’t last more than a year.

In another segment, a mother penguin is described as being beyond consolation over the loss of her chick, a slick bit of penguin mind-reading. At least Freeman’s cooings over penguins necking (it does look very much like certain teens at the mall) are an improvement over the original French version of the film, in which humans were scripted to speak imaginary penguin dialogue.

In “Grizzly Man,” it’s not the director/narrator but the true-life subject of the film, Timothy Treadwell, who repeatedly tries to convince his own video camera that he and the Alaskan grizzly bears among which he camps each summer are buddies and co-communicators. Treadwell and his girlfriend were killed in 2003 by a grizzly who that had a different worldview. Treadwell saw himself as the bears’ protector, though his romantic vision really endangered not only himself but the bears; by coming in continued, close contact with wild and remote animals, Treadwell may have dangerously acclimated them to humans.

The penguin trek at first seems a ridiculous way to assure reproduction; it is hard to see anything like intelligent design in such inefficiency. Then, as the ice crumbles in warmer weather, it becomes clear that this arduous journey is an evolutionary necessity. If the eggs were laid any closer to the sea, the chicks would have ended up underwater before they were capable of surviving. And here is where human similarity to animals becomes uncomfortably clear. Maybe we romanticize animals because we romanticize ourselves. Boxes of chocolates, bouquets of flowers, anniversary dinners -- is this love, or just the extreme way we have evolved to ensure that the species continues?

Imagine the penguin-eyed view of a typical romantic comedy from Hollywood. “Oh look,” the female penguin says during the gushy scenes, “the humans are engaging in instinctive behaviors that have evolutionarily led them to procreate.” “Nonsense,” says the male. “You’re ornithologizing again.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.