A Bible Textbook Begat by Church-State Separation

- Share via

Who asked, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Was it Cain, Noah, Abel or King David?)

What happened on the road to Damascus? (A: Jesus was crucified. B: Mary met an angel of the Lord. C: St. Paul was blinded by a vision from God. D: Judas betrayed Jesus with a kiss.)

Only a third of the American teenagers in a nationwide Gallup poll last year correctly answered the first question, attributing the quote from Genesis to Cain. And, a similar percentage of the 1,002 teens in the survey were aware of the story of St. Paul being blinded by a vision from God on the road to Damascus.

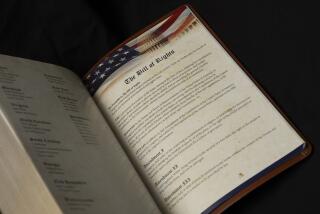

An overwhelming majority of the nation’s students are biblically illiterate, educators say. Yet, they add, knowledge of the Bible, its characters and references is essential in understanding Western literature, art, music and history even for students who come from other religious traditions, are agnostics or are atheists. On Thursday, a new textbook designed to help teach public high school students biblical content without violating the separation of church and state was released in Washington, D.C., by the Bible Literacy Project, a nonprofit group that promotes the study of Bible content, not belief, in public and private schools.

The project, funded by the John Templeton Foundation, has the endorsement of scholars, some 1st Amendment experts and officials from such organizations as the American Jewish Congress and the National Assn. of Evangelicals. Titled “The Bible and Its Influence,” the 392-page book, co-edited by Chuck Stetson and Cullen Schippe, is a product of years of planning, including the Gallup poll of teens’ biblical knowledge. (It is listed for $67.75 to individuals and $50 for schools.)

“It was created to satisfy all constituencies involved in the heated public debate about the Bible in public schools,” said Stetson, chairman of the Bible Literacy Project, which is based in Fairfax, Va.

He said the book treats various faiths with respect. It also meets, he said, the “consensus standards” endorsed by teachers unions, religious groups and civil liberty organizations as rules for handling the Bible in public schools. In 1998, the Clinton administration issued guidelines under which public schools may teach about religion, including the Bible as literature, and the role of religion in history but may not provide “religious instruction.”

Marc Stern, general counsel for the American Jewish Congress, calls the new textbook “a signal achievement.”

“Without question, it can serve as the basis for a constitutional course about the Bible in the nation’s public schools,” Stern said.

But the Rev. Barry W. Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said his group would look “very carefully to see if it meets constitutional requirements.”

“The courts have held that objective study about religion is constitutional in our public schools,” said Lynn, an ordained United Church of Christ minister. “However, I am very wary of organized efforts to introduce Bible classes into the curriculum. This effort may be well intentioned, but it comes at a time when organized pressure groups are seeking to undermine the religious neutrality of our schools.”

Robert Alter, a professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at UC Berkeley who reviewed the book, said he was impressed by it.

“I very much liked the way it relates the Bible to the later literary texts and political and historical events and so forth,” he said. “It conveys that this is not just ancient, dead and holy documents, it has something to do with our ongoing lives as a culture.”

For example, the chapter on the Psalms -- sacred songs -- begins with a list of key texts, accompanied by an explanation of how the Psalms are different from other poetry of the time and how translations have influenced the English language, culture and music.

The narrative is accompanied by illustrations of Marc Chagall’s painting “King David on Red Ground,” as well other works of art as examples of the influence of the Psalms on people.

It notes that when people want to express strong emotion, they often turn to music. The book asks students to think about: “How important is your collection of songs? What do the lyrics mean to you? How does your music help you communicate with your friends?”

In the New Testament section, students are told that the Gospel of Luke consists of “two volumes,” Luke and the Acts of the Apostles. Readers are asked to “discover” how Luke inspired writers, artists and filmmakers with his narratives.

“Luke traced not only the life, teachings and death and resurrection of Jesus, but also the beginnings of the Christian community,” the narrative reads.

Tom Wiegman, an English teacher at Sunny Hills High School in Fullerton who has taught a popular elective course, “Bible as Literature,” since 1992, used a draft of the book last year as a study guide and plans to use the final text as soon as he can order the books. He and his students liked it, he said.

“I had a kid who on the first day told me ‘I am an atheist,’ ” Wiegman recalled. “He turned out to be the best student in the class.”

Genesis is particularly strong as literature, Wiegman said. “Characters are interesting. There are so many stories.”

He said he assigns his students to write an essay on the character of King Saul, because “his story fits the elements of tragedy.”

Inevitably, when they get to Job, students ask, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” said Wiegman.

April Brown, a senior in Wiegman’s class, says the course is helping her learn to read the Bible in a different way.

“I just never really thought of the Bible as literature,” said Brown, who said she was a devout Christian. “I read it, but I thought of it [only] as a sacred book.”

Leland Ryken, professor of English at Wheaton College, a Christian school in Wheaton, Ill., was among the 40 experts asked to review the book in draft form for accuracy, scholarship and legal ramifications. He said he had no reservation about using the textbook in public schools.

“The book presents information and does not proselytize,” he said. “The only person who might object to the book is someone who believes that people should not be allowed to know about the Bible. Students who enroll in college without biblical knowledge handicap themselves from the outset when they come to study English and American literature.”

Still, there is lingering confusion and extreme caution among the public and educators about the legality of teaching about the Bible in this way, experts say.

“Just mentioning the Bible and the public school in the same sentence can start a fight -- and people start shouting,” said Charles C. Haynes, senior scholar at the First Amendment Center, a nonprofit free speech education group.

Still, he said he was confident that the new book would pass all legal tests it may face.

“This is one that finally gives schools what I could characterize as a safe harbor,” Haynes said. “This text enables them, if they want, to have a Bible elective that is academically sound and is also constitutional.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.