Still standing, like the rest of the city

- Share via

MY mother was born in 1928 on an orange grove in Covina. She was proud of the fruit — Florida, bah. Yet in her dying days, as she recalled that farm, it wasn’t the oranges and lemons and limes that she talked about. It was the oak tree at the end of the farm drive.

For those who were born here, whose parents were born here, who experienced Los Angeles as a bucolic place, the symbol of California was never an orange tree, not a eucalyptus, not a palm. The surest shade, the softest seat, the happiest place in the land was under an oak.

Once Southern California was covered with oaks. Oaks shaded farmers while citrus bedeviled them, leaves turning yellow from the alkaline soil and those stinking white blossoms dropping in frost. While orange leaves curled up with drought, oaks clicked with life. Deep beds of mulch housed lizards, bushtits made drowsy leaps from the boughs.

Most Californians no longer know the comfort of an oak, or the whispering rhapsody of their shade. Valley oaks are all but gone from the region, felled for farming, then houses. The Engelmann oak, so common a century ago that it was nicknamed the Pasadena oak, is so rare now that most of us have only experienced its luminosity standing before a plein-air painting.

I’ve heard art historians say that the painters were imitating the French, but I’m not so sure. The trees really do shimmer. Their elliptical leaves seem almost blue — an effect of the waxy coating that helps the leaves store water. These extend from uniquely delicate stems that work as levers, subtly turning the leaf throughout the day so it deflects light rather than burning up in its direct heat.

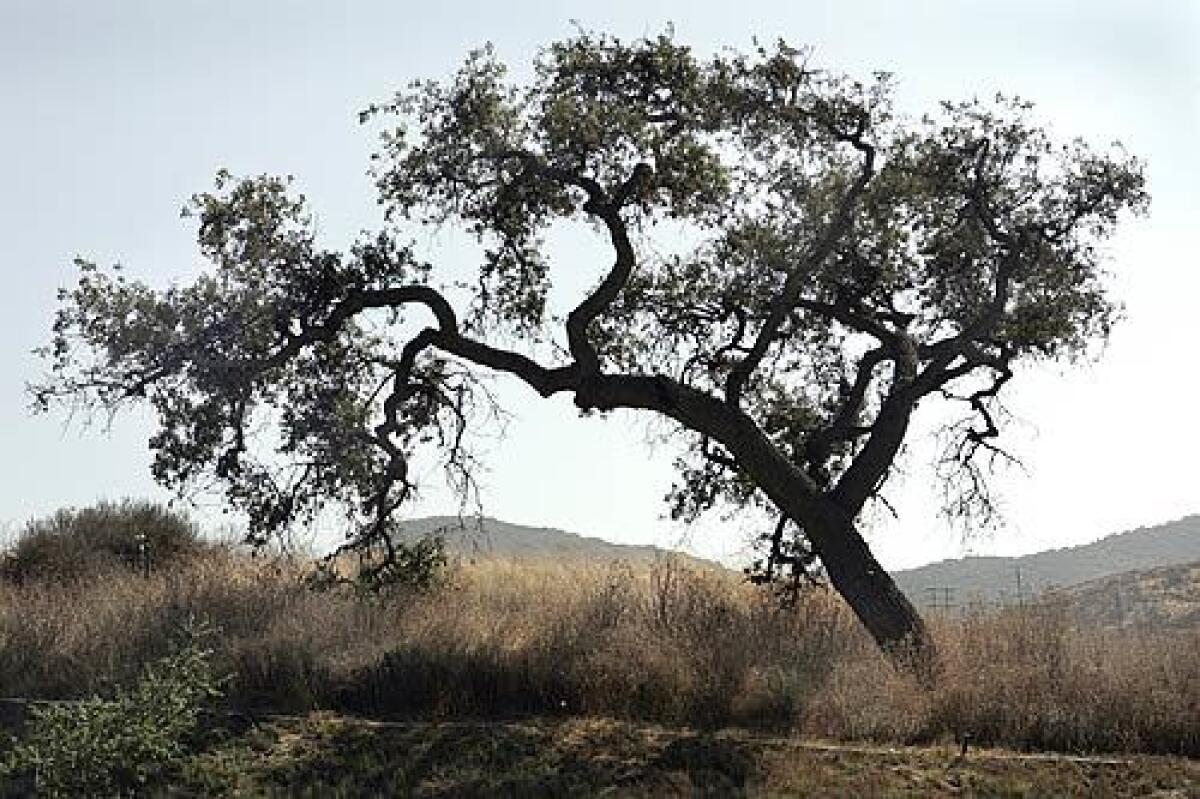

Today, most of our oaks are coast live oaks, gray-barked, olive-leaved trees most immediately identified by the tweeting from within the ever-green canopies. To experience their magic, go to the Rose Bowl, then hike up along the lips of the arroyo. There you will find one of the most thrilling old stands of the trees in the city, with the swooning wild habits shaped by wind and slope, not nursery and stake.

For some reason, they are not often planted. They aren’t sold in Home Depot and an urban myth dictates that they grow slowly. They don’t; they grow like basketball players in puberty. However, across the developed basin, their yearly cycle of regenerating through acorns forgotten by scrub jays has ended with modern yard care. The jays tend to cache acorns in hedges, safe from the attentions of cats. Then the saplings are routinely beheaded by pruning crews.

My family took my mother home to Covina as she was dying. The place was much changed. The farms were gone, citrus too, but neither was what she spoke about. That oak was what she remembered. It was what made this place home.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.