When we talk about love

- Share via

TO detect and decode the subtext of “What It Used to Be Like,” a memoir by the first wife of late poet and short story writer Raymond Carver, it is useful to consult the biographical entry for Carver in “The Dictionary of Literary Biography.” Tess Gallagher, the poet whom Carver met in 1977 and married a couple of months before he died of cancer in 1988 at the age of 50, is mentioned 17 times. But Maryann Burk Carver, his wife of 27 years, is mentioned only once.

Now, Maryann Carver has written herself back into his life story. “I’m the ‘Maryann’ you find in Ray’s poetry,” she declares in one angry and emblematic passage. “I’m also in some of the women in his short stories. I was a source of inspiration for Ray as he imaginatively recast incidents from our lives into his poetry and fiction. I was the sounding board who knew his friends, his whole family, and the brilliance of the man long before he was anybody’s notable author. You don’t just toss that aside when you hit a bad patch.”

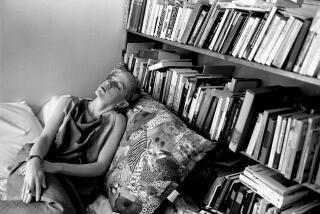

Her book is much more than a cry for attention from a spurned first wife. She brilliantly evokes small-town life in America in the 1950s as well as the seismic cultural upheavals of California in the 1960s. She tells the shattering tale of a storybook romance blighted by alcoholism, adultery and abuse. Above all, she is a woman who simply refuses to be ignored, and she lays a claim to her rightful role in the life and work of the writer who has been called the American Chekhov.

Maryann Carver begins by recalling her ardent courtship by young Raymond Carver in the early 1950s in a little town south of Yakima, Wash. Not yet 15, she was working as a waitress in a doughnut shop. “A tall, dark curly-haired young man walked in,” she recalls. “Ray was as handsome and sophisticated as a guy in a TV ad.” Their first date was a double feature at the local drive-in with “Blackboard Jungle” at the top of the bill. “Who needed to read romance magazines? This was the real thing,” she writes. So real, in fact, that the young couple eventually “crossed the line,” as she puts it, and when she found herself pregnant at 16, the 19-year-old Carver married her.

As if to remind the reader that Raymond Carver was not always the revered master that he grew up to be, Maryann pauses to point out that the favorite books of his adolescence included Buck Rogers and the jungle adventures of Edgar Rice Burroughs. As a young man, however, he had loftier ambitions for himself. “I’m going to be a writer, Maryann,” he vowed. “A writer like Ernest Hemingway. In fact, I’m going to be such a great writer, I’ll be able to flip the bone to the world.” Young Maryann was stirred by such chest-pounding: “This was the most exciting thing I had ever heard in my life. Conviction ringing in my voice, I said, ‘Ray, I’ll help you!’ ”

The theme of Maryann Carver’s memoir is writ large in these fateful words. As she shows us, in intimate and often heartbreaking detail, she was the muse who believed in his literary genius when he was still pushing a mop as night janitor at a state hospital, the helpmate who worked long and hard as a waitress and a schoolteacher (and still found time to raise two children) so he could polish the poems and prose that would later make him famous. It was Maryann Carver, for example, who read and praised the writing exercises that he churned out as a student of the Palmer Institute of America, an L.A.-based correspondence course whose ad he had seen in a pulp magazine. “I was amazed at what Ray wrote!” she enthuses even now. “He was great.”

But she candidly admits that her young husband was always tempted to stray and even bolt. Shortly after the birth of their first child, Raymond Carver announced to his young wife that he wanted to spend two or three years in Spain, “after which he’d come back to me and the baby.” Her response is a measure of her courage and strength of character: “I don’t think you should be thinking about Spain right now, Ray,” she admonished him. “Ernie’s already done it.”

Raymond Carver was ultimately rewarded with critical success and a cult following, but it would be years before his exquisitely crafted short stories saw print. Carver enrolled in John Gardner’s Creative Writing 101 at Chico State College -- Gardner, already an inspiring figure to his students, had not yet published a word of his own -- and Carver was later befriended by Gordon Lish, the influential fiction editor of Esquire, who man-hauled him to the heights of the New York literary establishment. “I felt that Gordon’s m.o. was to make Ray’s stories more hip, slick, and cool,” writes Maryann, “rather than soulful and real, the way I liked them.” Each step up the mountain, however, was a step away from his first love.

“You know, Ray is a great artist,” Lish told Maryann. “If you would just let him go, if you would just free him from the exigencies of his life, there is no telling how far he could go.”

“I know he is a great artist,” she retorted. “I did before anyone else.”

Raymond Carver may have been an American original, but the story of his abandonment and betrayal of his wife and children is an old and unremarkable one. Always blessed with swaggering good looks, Carver discovered that there are more than a few women who will gladly go to bed with a famous writer -- or even a not-so-famous one. And he discovered the comradeship of fellow writers who preferred drinking to sitting down and writing. He began to seek out writing conferences and visiting lectureships, and she began to find perfumed love notes in his wallet. As Lish had predicted, she became an impediment to Carver’s reinvention of himself as a famous (and famously high-living) writer.

“I was presumably a nobody. Not an artist, not creative -- just a parasite on the Great Man,” she explains, recalling how she was treated when her husband was enrolled at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1960s. “No one at these cocktail parties and gatherings gave writers’ wives any credit. But they worked so that their husbands could write. They kept the children quiet. They edited and suggested and consoled their Great Men through years of rejection slips and meager income. When and if the good times arrived, they could only watch as superficial friends surrounded the newly acknowledged Great Man, eager to take him away to bigger and better things.”

Clearly, Maryann Carver wants just revenge against those who spurned and even defamed her. Thus, for example, she points out how the poignant, comical and painful moments of their married years show up in specific stories that Carver would later write, and she seeks to debunk the notion that she was the root cause of his alcoholism. For that reason alone, “What It Used to Be Like” must be regarded as a new and indispensable source for any serious study of the life and work of Raymond Carver, and it will surely send old and new readers to the Carver canon.

“Let me unknit the whole cloth of our experiences, and show something of how Ray was transformed into ‘Raymond Carver, author,’ for better or worse,” she explains. “And how I became the professional wife who couldn’t rescue him.”

Above all, she wants us to recognize that she, too, is a writer with something worthwhile to say. Tellingly, she has titled her book with a phrase that is strongly reminiscent of the suggestive, enigmatic phrases that Carver chose for his own stories. And even if the early chapters of her book are somehow more compelling than the later ones, Maryann Burk Carver has produced a memoir of exceptional poignancy, a passionate and ultimately tragic life story that would still be fascinating even if it did not feature the American Chekhov as its leading man. *

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.