When they don’t save lives

- Share via

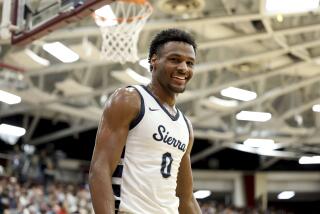

WHEN the heart of a young athlete is struck by a storm of faulty electrical impulses, the effect can be sudden, shocking and so unexpected that teammates, coaches and even emergency medical responders may not immediately recognize it for what it is: a heart attack.

A small study in the July issue of the journal Heart Rhythm suggests that such events are overwhelmingly fatal as well, and that cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automatic external defibrillators, life-saving to so many heart attack victims, have been of little use in these cases.

Reviewing the records of nine intercollegiate athletes who experienced sudden cardiac arrest between 1999 and 2005, Dr. Jonathan A. Drezner and coauthor Kenneth J. Rogers found that eight did not survive, even though they received CPR and, in seven cases, a shock from an AED.

Emergency responders provided timely and appropriate care, but the survival rates of these young athletes was “significantly lower than expected,” said Drezner, a family and sports medicine specialist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The athletes’ youth, excellent physical conditioning and previous history of good health only deepened the mystery, he added.

The effectiveness of AEDs in averting heart attack death has been strongly demonstrated, and in recent years the devices have proliferated in public places. Most states have adopted laws requiring easy access to AEDs in public buildings, gyms and health centers.

But the success of heart-shockers was established mainly on older adults. The study by Drezner and Rogers, of the University of Pennsylvania, is among the first to question their effectiveness in a narrower population.

Why the difference? Sudden cardiac arrest in adults is most often caused by atherosclerosis, a build-up of plaque in the arteries. But most of the stricken athletes in the study were found to have suffered from structural heart disease, in most cases a condition in which the heart is abnormally enlarged.

Sudden cardiac arrest in patients with such hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may be more resistant to AED use, Drezner said. In addition, he suggested, the intensity and duration of exercise before the event may also have affected survival.

But Drezner also cautioned that it is too early to conclude that high schools, camps and colleges have no use for AEDs. It is possible, for instance, that resuscitation and defibrillator use could still save lives in this population but would have to be delivered earlier to be effective.

The challenge in achieving that, he added, is that no one -- including emergency responders -- is primed to suspect that a heart attack is underway in such cases.

Many coaches, in contrast, assume at first that the problem is heat exhaustion and thus may lose critical moments to disbelief or confusion.

That should change, Drezner said.

“When you have a collapsed and unresponsive athlete, I think we need to assume it could be sudden cardiac arrest until proven otherwise,” he said. “If an AED is readily available, we need to immediately retrieve it, apply it to an athlete and use it if appropriate.”

Finally, he said, because emergency medical personnel can wrongly believe they feel a pulse, it’s best to let an AED make the call. Most have built-in pulse-monitoring devices.