A Chinese shot that resounds around world

- Share via

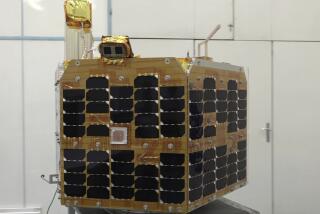

TAIPEI, TAIWAN — The Fengyun -- “Wind and Cloud” -- 1-C weather satellite was a proud worker in China’s space program. Launched in May 1999, it provided a wealth of information that scientists used for forecasting floods, sandstorms and disturbances in space caused by solar activity.

Now it has been reduced to a nebula of debris. And that may prove to be its most lasting legacy.

In January, China blasted the Fengyun 1-C into oblivion with a land-based antisatellite missile from its southwestern Xichang spaceport. It was the first kill of a satellite by a land-based missile ever conducted by any nation, including the United States and Russia.

The message was hard to miss: China is ready -- and increasingly able -- to challenge the U.S. military advantage in space.

“Competition is moving toward the new frontier, space,” said Arthur Ding, a research fellow at Taiwan’s National Chengchi University.

To space and military experts, China’s success is no surprise -- its military-run space program has taken a great leap forward in recent years.

It launched its first manned space flight in 2003. A second mission in 2005 put two astronauts into orbit for five days, and a third manned launch is planned for next year. This year, China plans to launch a probe that will orbit the moon.

But some see the antisatellite missile as evidence that China’s program is taking an alarming direction.

“The successful test of a Chinese direct-ascent antisatellite weapon represents a new and dangerous phase of Chinese foreign policy,” said Tom Ehrhard, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel and senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a private military think tank.

“Despite official statements about its ‘peaceful rise,’ China aims to challenge the internationally recognized sanctity and neutrality of the ‘commons,’ those areas like international waters, airspace, cyberspace and space itself,” he said.

Satellites are already the eyes and ears of the U.S. military, used to guide missiles to their targets, provide detailed information on enemy positions and movements and make immediate, global communications possible. The next step, first envisioned during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, would be weapons such as lasers that could be used from space to destroy or disable enemy satellites or possibly even targets on the ground.

U.S. military planners have long warned that the satellites they depend upon are vulnerable. A 2001 report by a commission headed by Donald H. Rumsfeld, then Defense secretary-designate, said the U.S. was “an attractive candidate for a space Pearl Harbor” and that the country needed to develop systems to protect its satellites.

China and Russia, which like Washington have signed the 1967 treaty outlawing weapons of mass destruction in space, advocate a complete ban on antisatellite and other space weaponry. The Bush administration, however, blocked a U.N. resolution to that effect in 2005. Beijing and Moscow resubmitted a similar proposal this year.

Beijing says it wants to bring Washington back to the negotiating table, and that its satellite kill was in line with its larger goal of demilitarizing space.

“China opposes the weaponization of space and any arms race,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Jianchao said. “The test is not targeted at any country and will not threaten any country.”

Russian President Vladimir V. Putin stressed after the satellite kill that Moscow continued to oppose weapons in space, and he criticized Washington, not Beijing, for planning space-based weapons, which he said was the reason behind the Chinese test.

“We must not let the genie out of the bottle,” he warned.

The United States and the former Soviet Union also have shot down satellites, but didn’t use ground-based missiles. The U.S. did it in 1985 with an air-launched missile, and the Soviets used a hunter satellite to approach its target and then fire at it.

Bill Sweetman, an analyst with Jane’s Space Systems and Industry, said the Chinese test didn’t violate any treaties, but deliberately hit a sensitive nerve.

“The Chinese are aware of a difference between them and the U.S.: The U.S., and Western forces in general, are highly dependent on low-Earth orbit assets such as imaging spacecraft and GPS, but the Chinese are not,” he said.

The test, he noted, was sure to hold Washington’s attention for years: Debris from the satellite will continue to float in space, a hazard to other spacecraft. “You fill low-Earth orbit with high-velocity buckshot,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.