Vaccine industry is being revived

- Share via

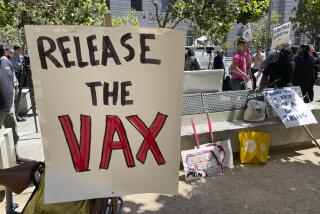

Breakthroughs in technology, increased funding and higher profits are spurring a boom in vaccine discovery and development that could save or improve the lives of millions of people by attacking such scourges as cancer and malaria.

Three new vaccines arrived on the market in 2006, the most in a single year. They include vaccines for the human papillomavirus, linked to cervical cancer, and for rotavirus, which causes severe diarrhea and kills 600,000 children globally each year. Another prevents shingles in the elderly.

As early as the end of the decade, scientists say, there may be new immunizations against herpes simplex and rheumatoid arthritis and a better seasonal influenza vaccine.

Researchers also are talking about a potential vaccine within five years to fight malaria -- long one of mankind’s deadliest and most elusive adversaries.

Other scientists are making progress with what are known as therapeutic vaccines, which fight already diagnosed diseases or conditions, including cancer and Alzheimer’s, or addictions to substances such as nicotine, by “teaching” the body to fight back. They’re further down the road but hold the potential to transform medical care, experts say.

“It may turn out we have a perfect storm here of several different things coming together at the right time. This is a tremendous time of opportunity for both the developed and the developing world,” said David Fleming, director of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s global health strategies program, which has made vaccine development and access a cornerstone of its mission.

“It’s clear there is a renaissance going on around vaccines,” said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “We have made more progress with some [vaccines] in the past few years than we have in the past 30.”

The current immunization boom could rival or even surpass the Golden Age of vaccine development between the late 1940s and early 1960s, experts say, when scientists such as Jonas Salk discovered inoculations for polio, flu, mumps and measles. But relatively few vaccines were found in the decades that followed, partly due to lack of profitability for drug companies and reduced vaccine research funding.

Perhaps the best evidence of a vaccine revival is that the pharmaceutical industry is returning to the market.

Drug giant Pfizer Inc., which shuttered its human vaccine unit in 1976, reopened it in the fall by acquiring a small British vaccine company. Even with planned layoffs announced last week, Pfizer says it intends to increase funding in its vaccine business.

Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline recently have invested billions expanding their vaccine trades by buying up smaller players and expanding research programs.

Jean Stephenne, president of GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, expects his company to have five new vaccines in the next five years and that its vaccine business will grow from 6% of the company’s sales this year to 14% by 2010.

Overall, the number of vaccines in development has risen from 285 in 1996 to 450 today.

Drug executives say they can charge considerably more for today’s vaccines -- up to several hundred dollars or more -- versus a few dollars for older vaccines.

Prevnar, a vaccine introduced in 2000 to treat pneumococcal pneumonia -- the cause of up to a quarter of all community-acquired pneumonia cases each year -- runs about $250 for a four-shot series. It became the first vaccine to clock $1 billion in annual sales, giving it so-called blockbuster status.

Overall, the vaccine industry rang up $10 billion in sales in 2005, up from $6 billion in 2002. The market is estimated to reach $15 billion by the end of the decade.

Other factors increasing industry confidence in the sector: more funding from donors like the Gates Foundation, and novel proposals for increased vaccine research.

Typically, Third World countries can’t afford to buy new vaccines and don’t get access to them until a generation after their introduction, if ever. The lack of potential profits has blunted many drug companies’ interest in researching and producing vaccines to treat diseases, such as malaria, found predominantly in poorer countries.

But that is slowly changing. At the Group of 8 summit in Russia last year, several countries proposed upfront financing for vaccine development, creating incentives for manufacturers.

And Geneva-based GAVI Alliance, a partnership created in 2000 that counts among its sponsors the United Nations, the World Health Organization and the Gates Foundation, is investing hundreds of millions of dollars to expand vaccine research and distribution.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, last week, GAVI announced it would commit an additional $500 million over three years to strengthen healthcare systems in poor countries, a key problem in implementing vaccine programs in many locales. The organization says it has prevented 2.3 million deaths from disease since its inception, including 600,000 last year.

“The GAVI story is probably one of the greatest success stories of all time,” Bill Gates said Friday in an interview with CNBC.

Vaccine access in industrialized countries can also be spotty. In the U.S., African Americans and Latinos have significantly lower immunization rates than other groups. And when a vaccine arrives on the market, it’s not guaranteed to be covered by insurance.

While insurers deny it, doctors say the companies often wait a year or more before deciding to reimburse patients for a vaccine, hoping an initial surge of people will get immunized on their own dime.

This fall, Kelsey Boesch, 18, of Los Angeles paid about $300 for Gardasil, the vaccine against HPV. The three-shot regimen wasn’t covered by her family’s insurance.

“I hadn’t heard about it, but when [my doctor] explained it to me, I didn’t think twice,” Boesch said.

Experts say mounting scientific and business momentum around vaccines could stall at any time, and several promising vaccine candidates remain in early clinical trials.

Last month, the federal government canceled its 5-year-old, $900-million anthrax vaccine program after the company failed to meet a deadline to test it in people. Vaccines for major killers like HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and tuberculosis remain years, if not decades, away.

And drug companies have previously dipped their toes back in the vaccine market only to leave shortly after.

But even if only a handful of additional immunizations are found, it could have enormous impact on global health.

Malaria kills up to 3 million people a year. A less-fragile supply of flu vaccines could also have a major effect.

Vaccines are weakened or killed parts of bacteria or viruses that are injected into the body to stimulate antibodies that then provide immunity against that bacteria or virus.

Scientifically speaking, the last wave of vaccines half a century ago went after many of the “low-lying fruits but didn’t help us with the more complex viruses and bacteria,” said Warner Greene, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology at UC San Francisco.

The fact that half of vaccine manufacturers dropped out of the market by the late 1970s exacerbated the problem.

But Greene said major recent advances in vaccine technology had made finds considered unattainable a decade ago look possible.

Improved understanding of immune responses has led to more elusive vaccines, like the ones that have arrived in recent years. Better understanding of the genetic structure of bacteria and viruses, and how to get the body to respond to them more effectively, is fueling the growing optimism for malaria vaccines and other treatments.

In 2004, a small clinical trial of 2,022 children in Mozambique found an experimental vaccine cut the risk of developing severe malaria by 58%.

Separate advances are likely to increase the ability to produce influenza vaccines for routine immunization and, possibly, to protect against a global influenza pandemic.

Traditionally, flu vaccines are grown in millions of fertilized chicken eggs, which can take up to six months. The lengthy process makes it hard for drug makers to keep up with mutating flu strains and limits the amount of vaccine they can produce quickly each flu season.

The egg-based method is problematic for bird flu vaccines because the disease threatens chickens and the egg supply needed to grow the vaccines.

So pharmaceutical companies are developing two methods -- using cell cultures and DNA cloning -- that could speed things up.

Instead of growing the vaccines in eggs, scientists are trying to use cell cultures, which is how vaccines for chicken pox, hepatitis A and polio are made. This summer, the federal government awarded five companies a shared $1 billion to research and implement cell process, which could cut in half the development time for seasonal flu vaccines.

Researchers also are making progress with what are known as DNA vaccines especially for use against the flu. These are made with single genes of a virus, and injected into the skin to produce an immunological response.

Although no DNA vaccine has proved effective yet, scientists say it’s a much more direct method for immunizations that holds enormous promise.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Immunization boom

Vaccines recently approved or expected soon:

* Pneumococcal disease:

Approved in 2000

* Human papillomavirus:

Approved in 2006

* Rotavirus gastroenteritis,

children:

Approved in 2006

* Shingles, adults:

Approved in 2006

* Herpes simplex:

Expected arrival in 2008

* Rheumatoid arthritis:

Expected arrival in 2012

* Multiple sclerosis

Expected arrival in 2012

Source: Times staff