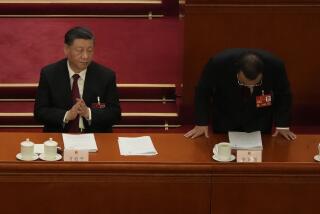

Mao’s successor as Chinese leader

- Share via

BEIJING — Hua Guofeng, one of the last of the early generation of Communist revolutionaries who was named briefly to succeed Chairman Mao Tse-tung, died Wednesday, Chinese state media reported. Hua, who is credited with putting China on the path to reform by removing the Gang of Four, was 87.

Sometimes dismissed as insignificant, Hua was a man caught between two eras who created a bridge over the gap before having the good sense to exit the political stage gracefully.

In the past, the Communist Party has waited several days to announce the death of a major current or former leader, giving political factions time to fight for position and the party time to control the damage.

Rumors of Hua’s death have been rife for days in Beijing, suggesting the announcement was delayed less for political reasons than to avoid spoiling the leadership’s big Olympics coming-out party. No cause of death was cited other than an “unspecified disease.”

“The most important thing is how relevant his death is to the politics of today, which shows how much China has changed,” said Steve Tsang, a professor at Oxford University. “I’m sure there’s an element of management in the announced timing. When he actually died, we don’t know, but I suspect it was in the course of the Olympics.”

Mao picked Hua to succeed him as a compromise candidate, unwilling to name a successor either from the radical Gang of Four, which included Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, or from the hard-line revolutionaries. Mao, on his deathbed, reportedly wrote in a message to Hua: “With you in charge, I am at ease,” although some doubt its authenticity.

But in what some credit as his biggest contribution during a two-year reign that started in September 1976, Hua destroyed the Gang of Four politically, allowing China to ease away from the Cultural Revolution. “Without him, it would have been much more difficult to get rid of them, so on that count his contribution was huge,” said Huang Nangping, professor at Peking University’s School of Marxism and Leninism.

Hua sparked criticism for the underhanded way it was carried out, however. A month after taking power, members of the hated group were invited to an 8 p.m. meeting in the Great Hall of the People’s Hall of Embracing Benevolence. The meeting was a sham -- the supposed topics of discussion included the design for Mao’s tomb -- and, once there, group members and their supporters were arrested by the army. Mao’s wife was picked up a short time later at her home.

Hua lacked a strong political base, however, and rather unimaginatively followed his predecessor in a movement dubbed the “two whatevers,” namely to resolutely follow whatever policy decisions or instructions Mao gave. At one point, Hua even copied Mao’s hairstyle.

Ultimately, he displayed little of the vision or intellect needed to wrench China out of the “Great Helmsman’s” shadow and put it on a new track. Unfortunately for Hua but fortunately for China, his rival Deng Xiaoping had these attributes and more, and Deng soon outwitted Hua politically.

Hua’s second great contribution, historians say, was to leave the stage voluntarily once he realized that he had lost the game, a rarity in that era when peaceful transitions of power were virtually unknown.

On paper, Hua was the most powerful Chinese Communist ruler ever, simultaneously holding China’s top party, military and government titles. Even Mao had Zhou Enlai as his premier. Hua could have used this to have Deng and other opponents eliminated, throwing the country into further turmoil, but opted not to.

“Hua chose to accept the party’s decision and step down, which deserves credit,” said Li Datong, former editor of the respected Freezing Point publication. “He was an honest, upright guy who wasn’t great on political skills.”

Hua was born into a poor family on Feb. 16, 1921, in central Shanxi province as Su Zhu, a name he later changed to Hua Guofeng because it sounded more revolutionary. His father died when he was 6. He attended technical school and by some accounts joined the Long March in 1936 before becoming a Communist Party member in 1938 as part of the fight against Japanese rule.

After eight years in the army, he held a series of local army and government posts between 1949 and 1971 in Hunan province. Mao’s hometown was in Hunan, and Hua’s decision to build a Mao memorial hall in Shaoshan caught the leader’s eye. In 1973, he was elevated to the Politburo before Mao tapped him for the top job three years later.

Deng was not initially strong enough to seize power, particularly given that he had just been denounced again in 1976 for inciting protests linked to the death of Zhou Enlai. Over the next few years, Deng chipped away at Hua’s titles and power until Hua’s retirement in 1982.

His last major public appearance was at a party congress in 2007 where a camera caught him gently dozing. As with many Chinese leaders, there are few details about his family life.

“He fought as long as he could, then was willing to be eased out,” said Oxford’s Tsang. “If he’d remained in power, China’s reforms would have been later and less bold, a testament to Deng Xiaoping. China wouldn’t have moved as fast as it has.”

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.