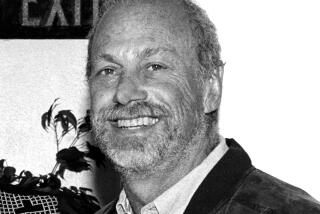

Guard at Warner Bros. Records lot acted as equalizer

- Share via

At Warner Bros. Records, Howard Washington was both the gatekeeper and the great equalizer, a security guard who stood out in a celebrity-obsessed town because he didn’t care if that was Madonna or Prince or David Lee Roth behind the windshield. If the small Burbank parking lot was full, he’d order the most famous of rock stars to park their cars on the street.

“Especially when everyone has an ego, getting into that parking lot was a bigger deal than anyone could know,” said Adam Somers, a former senior vice president at the label. “Howard’s word was law.”

Washington, whose career at Warner Bros. spanned 65 years, died Tuesday of complications related to pneumonia at Brotman Medical Center in Culver City, said Eunice Glover, his longtime companion. He was 98.

His stereo-wired guard shack -- known as “the philosophy corner” for Washington’s propensity to hold forth on the meaning of life -- was considered one of the more powerful offices on the lot. The inhabitant had a way with vegetables, tending a nearby garden, and a way with bureaucracy. He knew how to cut through clutter.

When Somers had to find a bulldozer in half an hour for a photo shoot, he managed it by placing a call to Washington, who said: “You think you can come up with a six-pack of beer and six cassettes?”

Washington had been forging connections at Warner Bros. since 1929, when he opened a shoeshine and carwash concession at the studio and struck up a friendship with studio boss Jack Warner. Washington used to recall how he would walk the lot at night with Warner, who cursed when he saw the lights on in the writers’ offices because he worried about the cost of replacing the lightbulbs.

Bob Merlis, former head of Warner Bros. public relations, said Warner “had special affection” for Washington, who was one of about 40 people who attended the 1978 funeral of the studio chief.

Howard William Washington was born July 15, 1909, in Norco, La. An only child, he ran away from home at 16 and came to Los Angeles on a freight train.

At 20, he started working at Warner Bros., but he left during World War II to serve in the Navy. He took another break from the studio in 1958 to sell real estate for several years.

Washington married and divorced five times, explaining that he mainly lived in an age of marriage, “not shacking up.”

He had a cameo in Busby Berkeley’s “Cinderella Jones” (1946) and appeared as a waiter in the Alfred Hitchcock film “Strangers on a Train” (1951).

After an independent facility was built for Warner Bros. Records in the early 1970s, Washington oversaw the parking lot until he retired in 1994 at 85.

The record label threw a party for his 80th birthday that was emceed by rock’s flamboyant Roth, who expressed fondness for the security guard with the booming voice.

He “was my first contact with the big corporate empire of the music business,” Roth told The Times in 1989. “Howard’s your first barometric reading when you get here.”

After the party, Washington explained his egalitarian attitude toward VIPs: “I treat them just like everybody else. I’ve been around stars. They’re human like everybody else.”

Employees at the gathering presented Washington with his own framed, platinum record titled, “Howard Washington on the Lot.” Among the cuts: “You Can’t Park Here,” “Park on the Street,” “The Lot Is Full,” “They Didn’t Tell Me You Were Coming” and the long version of “I Don’t Care Who You Are.”

In addition to Glover, his companion of 24 years, Washington is survived by a son, Nicholas; a daughter, Sondra Allinice; three grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren. Another son, Howard Washington III, died in 1965.

A memorial service will be held at 10 a.m. Wednesday at Angelus Funeral Home, 3875 S. Crenshaw Blvd., Los Angeles.

Memorial donations may be made to the United Negro College Fund, www.uncf.org.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.