It’s the end of the whirl

- Share via

He’s walked away from a midair collision and survived more than a few attempts to shoot him out of the sky. He’s plucked lost hikers out of narrow mountain canyons and threaded his way through tangles of power lines to pull schoolboys from flooded storm channels.

But today, helicopter pilot Tony Pachot just wants to pull off one final soft landing.

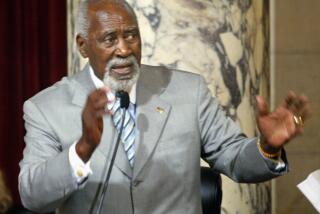

The pioneering Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department flier will end a 33-year career when fellow deputies stage a retirement ceremony for him in Lakewood.

Pachot, the Sheriff’s Department’s first black pilot, will have plenty of tales to tell if his buddies press him to reminisce about the old days.

Like his unforgettable first day on helicopter patrol, when he swooped in on a group of car-strippers in La Puente and a sudden wind shift sent him spinning into a nearby lemon tree.

Or the night a Compton Police Department helicopter collided with his as he hovered over a gang fight in South Los Angeles.

And the disorienting moment one moonless night during the riots that followed the 1992 Rodney King verdict, when exploding transformers caused a power failure that plunged the city beneath him into a horizon-less blackness.

Not to mention the heart-stopping pursuits that have landed him and his copter on the “World’s Scariest Police Chases” show more times than he can recount.

But Pachot worries that tonight’s farewell dinner at the Centre at Sycamore Plaza could be his most challenging moment.

“I’m afraid I’m going to get all emotional,” he says.

That’s a sentiment that is never on display in the dozen $2-million AS350 B2 Eurocopters that sheriff’s deputies fly each day out of their Aero Bureau base at Long Beach Airport. The department’s 25 pilots strap pistols to the waists of their flight suits when they lift off, prepared to chase down lawbreakers over 4,000 square miles of county territory.

Pachot, 60, of Ladera Heights, became a sheriff’s deputy as a reaction to being stopped in 1970 by a pair of Los Angeles police officers for an allegedly burned-out license plate light. It was pouring rain and the water company salesman was dressed in suit and tie as he traveled to meet his future wife, Darlene, for dinner.

The police would not let him retrieve an umbrella from his car, Pachot said. And then they appeared to purposely drop his car registration into the street’s overflowing gutter. “I was livid. That day I decided to become a cop so I could make sure others weren’t treated that way,” he said.

His move to the sheriff’s Aero Bureau came from a desire to fly the department’s fixed-wing airplanes. Pachot had a private pilot’s license and figured he could help ferry prisoners around and do aerial surveillance work. When he found out that all sheriff’s pilots are required to have a “rotocraft” rating, he set out to learn how to fly helicopters.

On his initial aerial patrol outing, however, his new career almost didn’t get off the ground.

“I had a loss of tail rotor control on my very first patrol assignment. We found the car-strippers,” Pachot said, recalling the La Puente incident. “But the wind shifted and the helicopter started spinning. I was about 15 or 20 feet above a backyard and I could see clothes blowing on the clothesline.”

He eventually gained control and pulled the helicopter up. But some in the La Puente neighborhood were angry at the disruption caused by the low-flying copter. One man ran out of his house with a gun and started shooting at Pachot’s craft as it gained altitude.

“A lady complained we tore up her lemon tree. When we landed, I found pieces of lemon pulp on the tail rotor. At the time, I didn’t think about getting hurt. I was thinking that people were probably wondering why they had made me a pilot,” he said.

There were other close calls too. Over East Los Angeles in 1989, his helicopter was struck by gunfire.

“I took two rounds in the fuel cell. At the time I had the police chief from Bangkok, Thailand, in the back seat.

“We could smell the fuel leaking out. At first, I wondered if I’d left the fuel cap off,” Pachot said.

It was after he made an emergency landing at King-Drew Medical Center that he discovered the two bullet holes.

“We started using self-sealing fuel tanks after that,” he said.

Searches for missing hikers in treacherous mountain terrain were frequent. More dangerous were rescues in urban areas. There, hard-to-see power lines are a constant hazard.

The rescue of two boys in 2001 from rain-swollen Big Dalton Creek near West Covina earned Pachot and his crew the “Rescue of the Year” award from an international helicopter pilots group.

The 1990 midair crash with the Compton police helicopter was Pachot’s scariest moment.

He was about 500 feet in the air, helping ground units at the scene of a gang fight near Florence and Central avenues, when the Compton helicopter flew in front of him.

“I saw a shadow. I couldn’t tell that it was a helicopter, but I knew it shouldn’t be there,” Pachot said.

“I pushed to the right and there was a tremendous boom. Suddenly, we were going straight down. My partner said, ‘We just hit Compton! I see him spinning down!’ I was thinking, we’re going down too,” Pachot said.

He was able to safely land in a schoolyard. The Compton helicopter managed to set down in a church parking lot. No one on either craft was hurt. But Pachot found that the “T tail” on his copter had been sheared off about 2 inches above the arc of his tail rotor.

It was later determined that the Compton pilot did not hear Pachot announce his position because he had turned down the volume of his flight radio so he could hear a Compton police frequency.

Despite increasingly crowded Los Angeles-area skies that are filled with helicopters from police and fire departments and TV stations, Pachot said it’s safer to fly now than it was when he started. That’s because pilots from the public and private sectors regularly communicate with one another and now fly under standardized rules.

Pachot, who hopes to start a helicopter charter company, said he’ll miss the view from his sheriff’s copter cockpit. Especially on summer days when he regularly spotted topless sunbathers in places like Malibu.

His boss, Aero Bureau Capt. Joseph Impellizeri, said he’ll miss Pachot’s cheery disposition. “I’ve never seen a guy so happy to come to work every day,” he said.

The unit’s chief mechanic, Larry Belden, said he will miss the souped-up cars that Pachot races on his days off.

“He used to endear himself to the mechanics by parking his Porsche in the hangar,” Belden said. “One day he parked right on top of the tools I had scattered out on the floor.”

That he won’t miss, Belden said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.