Pico Iyer on the tyranny of the moment

- Share via

It was already clear, in December of 1999, that books were a dying species. Already more people seemed interested in producing novels than consuming them, and when it came to serious works, there seemed more fascination with the writer than the writing. Books, I heard from two serious, bewildered editors in New York on the same trip, were now part of the “entertainment industry,” and a first-time novelist was as likely to be judged on the power of his author photo as on the character of his content. If, 10 years before, one might have read Joan Didion’s earlier work before listening to her or meeting her, now one was more likely to read her Google entries, everything that had been said about her, everything that she had said in idle moments. The days of YouTube, and judging an author, as well as her work, on her cover seemed already imminent.

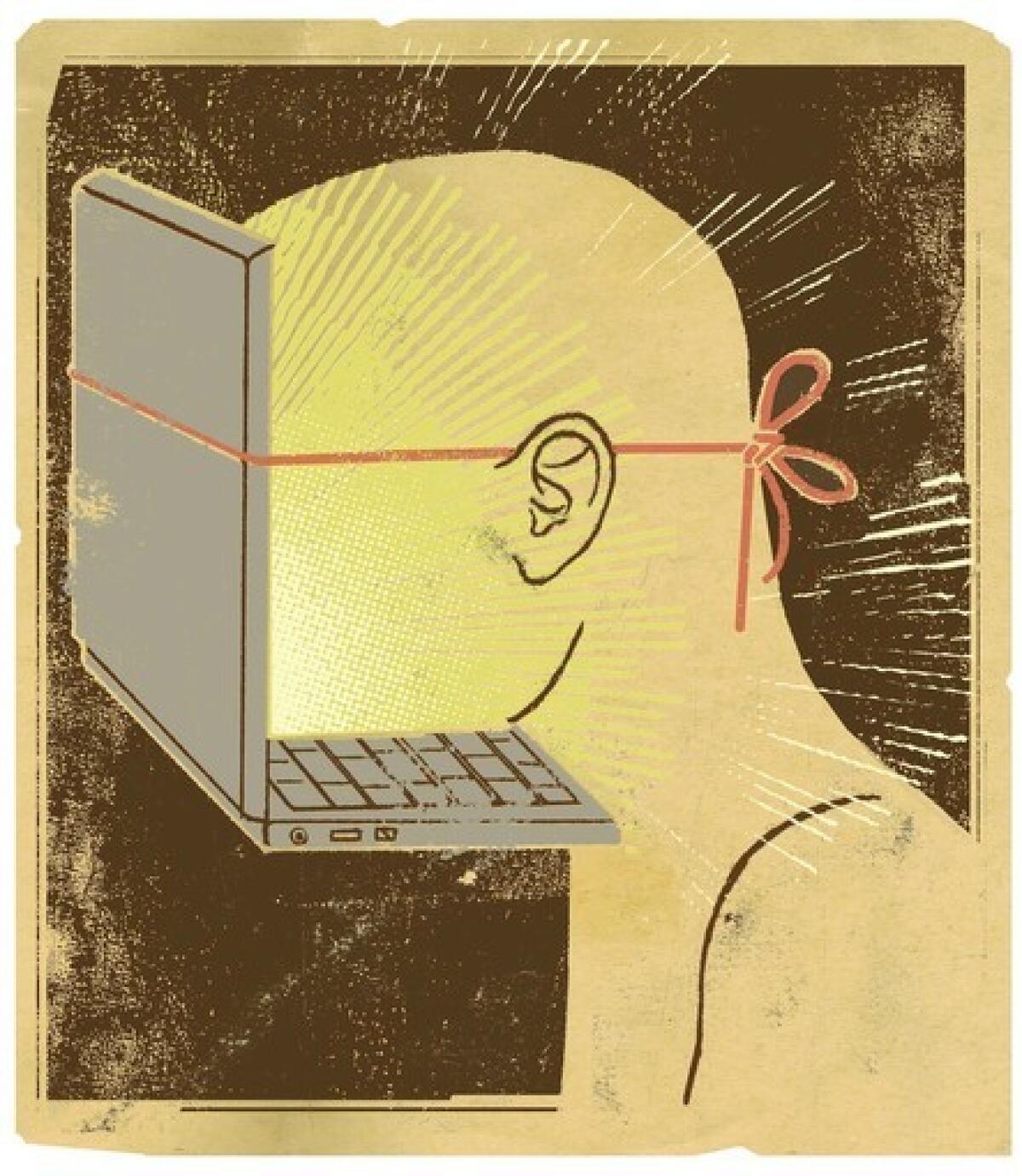

Even so, I don’t think I could have guessed, 10 years ago, how very quickly the icon and the image, in every sense of those new-century words, would erase so much that had been building for centuries. Memory is now seen in computer terms at least as often as in human ones, and blogging has set into accelerating motion a revolution in the very way we think of “reading” and “writing.” The global village has certainly produced a village commons -- you might as well call it the Internet -- but its rules and features seem much more those of a global city, a fractured, violent and screaming inner city expanded to the size of a planet.

In December 1999, ignoring global panic about Y2K, I took my mother to Easter Island to remind myself how even at the dawning of the 21st century there were places, many of them, where nothing was so rare as a piece of wood. Ten years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, however, I don’t think I ever imagined that those of us in the free-ish world would fall so quickly under the tyranny of the Moment. So much of our time, already, is contracted to the point of right now, that we’re locked, more and more, inside the windowless cell of the Present. Tiger Woods the hero seems ancient history already, and the latest convulsions in the Jon-and-Kate story, broadcast with every tremor, ensure that we’re trapped inside the latest millisecond.

It’s as if space has miraculously expanded, thanks to satellites and airplanes and Skype; but time has terrifyingly constricted, to this second that’s just vanished. Movies, more than ever, are made (or unmade) by their opening weekend; books last about as long as their first review or appearance on Jon Stewart, whichever comes first. In the old days, bands might be only as good as their last album; now they’re only as good as their last concert, which was probably webcast last night so you could see everything of U2 except what you love about them. The obituaries for our new president and his vision began on Jan. 21, 2009.

As planned obsolescence moves at the speed of light -- in Japan, where I write this, the “Royal Milk Tea”-flavored KitKat I fell in love with last week is already gone from the shelves -- I sometimes think that all we hunger for is liberation from the moment, and anything that will release us from the swarming, cacophonous, surround-sound, 24/7 dictatorship of Right Now. So long as we are human, we will always long for touching that part of ourselves -- or of one another and our world -- that doesn’t have a date-stamp on it.

So might books actually have a reason for being after all? A few days ago, I conducted a small experiment in my two-room apartment here in rural Japan. I spent two hours clicking through what are among the most literary and unhurried of the alternatives to books, the online versions of the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books. I came away with delectable snippets of information about Richard Holbrooke, American schools and the Obama campaign. I could talk now about any of these matters of current interest at a dinner-party with three minutes’ worth of wisdom. But I also felt, as I logged off, a little as I did when I worked four blocks from Times Square: wildly stimulated, excitingly up-to-the-moment, alive with ideas -- and with no time or space to hear myself think.

Then I picked up a novel a friend had just given me, the not very remarkable Swiss book “Night Train to Lisbon.” It’s a long way from Virginia Woolf or Emily Dickinson, and it didn’t begin to hold me as Alice Munro or Colm Tóibín might. But when I looked up from my reading, I’d forgotten what time it was, my self and my life seemed much larger -- and it was as if I’d stepped out of a traffic-jammed car on the 405 at 5 p.m. on a Friday and into a deep forest rich with secrets.

Define happiness, someone asked me recently. Absorption, I said instantly (it was an e-mail interview), and anything that gives me an inner life and a sense of spaciousness, intimacy and silence. The world is much better for many of us now than it was 10 years ago, and I never could have dreamed so many of us would have so many kinds of diversion, excitement and information at our fingertips.

But information cannot teach the use of information. And diversion doesn’t teach us concentration. Imagine a seven-hour-long heart-to-heart with someone who’s been saving up all her life for what she’s about to whisper in your ear. The medium that has been dying the whole century may be one way we can rebel against the hidden dictatorship of Right Now.

Iyer is the author, most recently, of “The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.