Making art in the now world

- Share via

“What it means to be an artist today -- where do we start on that one?” muses Ed Ruscha, almost nonplused. Finally, the soft-spoken art veteran decides : “It means facing a lot of information that’s going to be very difficult to take in and swallow because there’s so much of it.”

Once the ramifications settle in, he slyly drawls, “to grasp the total picture would make you wish you could go back to 1960 when things were a bit slower, almost like the Dark Ages.”

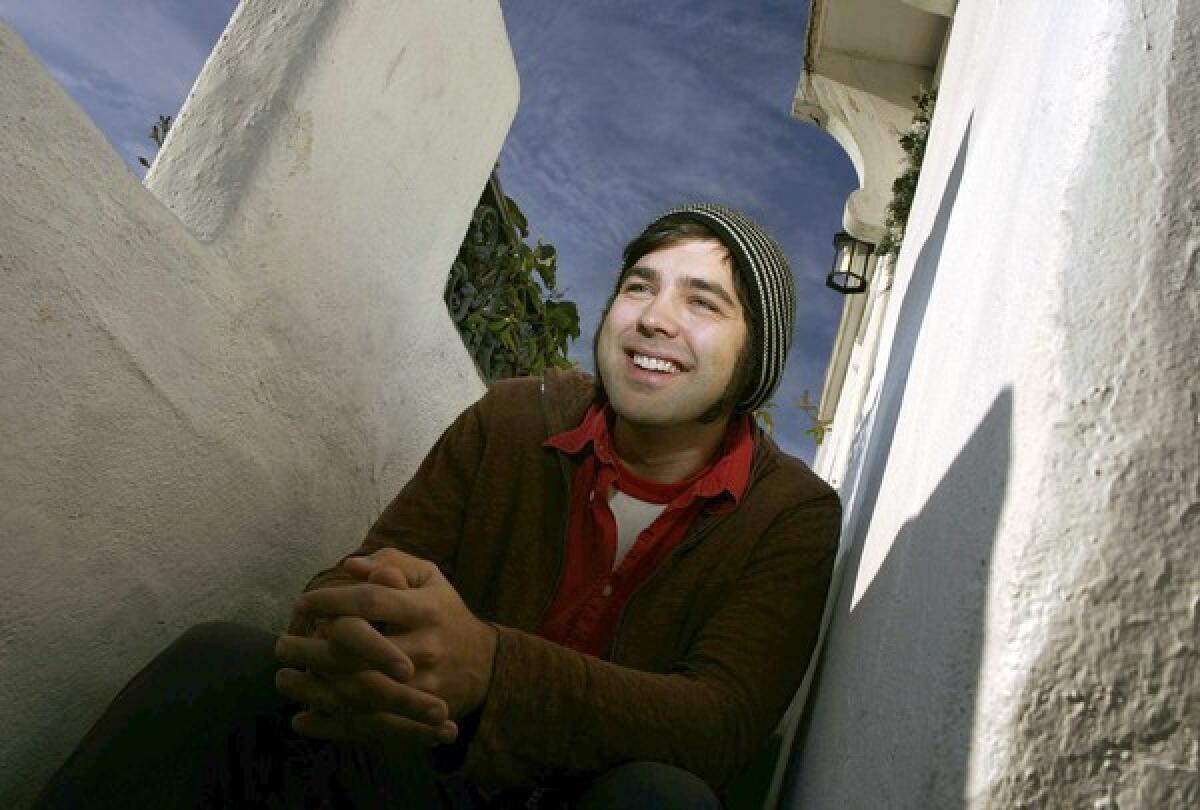

That dizziness finds a counterpoint with fledgling film director Michael Mohan on a cold December night in Westwood. His youthful exuberance contrasts with Ruscha’s measured bemusement: “It’s not like it’s going to be crazy; it is crazy, right now.”

Mohan has reason to be excited. His first feature, “One Too Many Mornings,” about two twentysomething guys who reignite their high school friendship, which he shot over two years’ worth of nights and weekends with a budget well under $50,000, will play the 2010 Sundance Film Festival in a new category dedicated to low-to-no-budget filmmakers.

Where Ruscha recoils at the opened floodgates of the Information Age, Mohan gushes: “There’s an audience for everything . . . if you say I want to express myself and people will see it, yes, that’s what in 2010 you can do.”

So even in the face of prolonged war and bitter recession, it seems 2010 is a pretty great time to be a young artist.

Ubiquitous communication and cheap digital technologies are empowering the striving artist who steadily cultivates his or her craft, challenging the cliché of the starving bohemian, or the superstar. At the same time, say many artists, an avalanche of output and constant accessibility might push them to rediscover the merits of handcrafted work, the necessity of disconnected contemplation and the joys of face-to-face human contact.

A recent nationwide survey of artists commissioned by the nonprofit group Leveraging Investments in Creativity found that more than half reported a decline in income from 2008 to 2009, two-thirds had at least one day job and almost 40% didn’t have adequate health insurance -- challenging times for a group 63% of whom reported income of less than $40,000 a year. However, an increasingly hyper-connected world might be stoking artistic enthusiasm: Seventy-five percent said it was an inspiring time to be in the creative arts. With access to new tools, you can create exciting work and reach new audiences; you just might not get paid well for it.

That doesn’t shake 35-year-old Brooklyn-based painter and digital animator Brian Alfred as he prepares for his 2010 show “It’s Already the End of the World” in New York: “If you chose to become an artist because you thought you were going to be the next Jeff Koons and make a trillion dollars, you might have picked the wrong field.”

Alfred doesn’t necessarily see an exodus of money from the art market following the financial crash as a negative. “That excess will probably be curtailed, thank God . . . a skull with a million diamonds on it, is that really what it’s about?” Now that he’s a father, he is simply grateful to put food on the table for his son and show his work to others: “I didn’t have any great expectations besides wanting to share my work with as many people as possible, so I’m happy as can be.”

Up to the task

For others, these crazy, hyperkinectic times are a challenge to be met with brio. “I think it means you have to be scrappy,” says Eliza Clark, a young playwright who just moved to L.A. from New York. “In some ways there’s a freedom in that kind of uncertainty, you just have to try to make it work . . . it means thinking nobody’s going to give me opportunities, I have to take them.”

In 2008, she and her friends raised $20,000 to put up her play “Edgewise” in New York. The play got great word of mouth, they sold out practically all their shows, and now Clark has come west to work as a writer’s assistant on AMC’s thriller “Rubicon.” And what was her play about? Three disaffected teenagers working at a fast-food joint in the middle of World War III.

So this brave new world might also be great material. Despite the post-apocalyptic title of his show, Alfred finds inspiration for his work in the rapid pace of change as he grapples with the ways technology breaks down barriers and brings exhaustive coverage of events with a mere mouse-click. “Information is experienced and shared in real time . . . we have so much stuff to see now, what do we actually take in?

“At the same time, that’s exciting because you can share ideas and information and images from all around the world instantly, and it sort of opens your eyes to all the things that pre-Internet, pre-technology deluge you never would have known about.”

This has stimulated him to move beyond his empty urban vistas to paintings of world flags, opposition parties and landscapes of political significance.

Veteran artists marvel and sympathize with the challenges facing the younger generation.

Theater director Peter Sellars lauds this engagement with the world as an imperative : “All the important things are not being discussed, while everything that is trivial is being discussed at exhaustive length.” He cites the conflict in Afghanistan, the California penal system and the drug wars as examples of under-examined crises. However, Sellars sees this as an invitation for artists to explore solutions creatively: “[As an artist] you’re supposed to make everything that’s unthinkable finally thinkable for people.” Still, he also cautions that the sensory overloads of YouTube and Wikipedia ring hollow without art to bring information to life: “What the Internet can’t give you is . . . what the feeling in the room is, what the vibe is.”

Anne Ellegood, senior curator at the Hammer Museum, sees that social awareness increasing among artists. “With the surplus of digital communication that everyone is experiencing -- many people can’t even keep up with the number of e-mails -- there’s this desire to sit down, have a coffee and have a conversation.”

In her field visits to young artists’ studios, she’s beginning to notice “a more sort of quiet, contemplative, process-based, handmade quality to a lot of work right now that seems to be appropriate for the moment.” According to Ellegood, in a world where answers can be had with a flick of the Google, we think we have to know everything. In her opinion, however, art can help us rediscover a sense of mystery and enjoy the pleasure of not knowing, or being able to know, the answer.

Ready to disengage

Certainly, the world of instant answers and total access doesn’t always live up to its promises for Mikel Jollett of L.A.-based band the Airborne Toxic Event. “We thought we’d get flying cars, instead we got pornography,” he laments.

As an artist, he also finds it important to disengage from digital connections that make it easy to broadcast your every move. “I think it’s good to have a little bit of distance. You need some time to experience your life before trying to go and make something with your ideas for people.” Jollett likes meeting fans and even e-mailing them; he just won’t let status updates replace human contact. “I like to . . . shake hands and see what people look like and how their eyebrows move.”

Still, having formed only in 2006, the Airborne Toxic Event has thrived in a digitally connected environment that has decimated the music industry. Its poignant, literary songs have propagated quickly, and the group just finished a first world tour with a sold-out homecoming at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Jollett thinks bands now have more space to develop a voice without feeling pressure to conform.

“Really what’s happened is these corporate giants that control everything have fallen apart. You can get further in a month than bands used to be able to get in two years . . . now you just have the tools at your disposal and you make those decisions yourself, you can make the cover art, you can turn up the reverb.” The do-it-yourself ethos has fostered a democratization he says is creating a middle class in music: “It used to be just an industry of stars and penniless vagabonds. Now, you’ve got artists who are making a living and they live in houses and cook on a stove.”

Future past

In many ways, that harks back to what Ruscha remembers as a young artist in the ‘60s. “When I first started painting there wasn’t that promise, and the idea of selling work to survive off of was practically unheard of.” Somehow the institutionalization of art -- the plethora of art schools, film schools, conservatories -- cultivated the notion of the professional. If that idea becomes untenable, Ruscha sees an upside. “Making a living and then making art, that’s not so bad. Artists throughout history have done that, where they’ve gone and done menial jobs and then come back and worked on their art. I think it’s a character-building program for anybody.”

Of course, with democratization, the challenge becomes standing out. Mark Lisanti, who found his audience blogging as the Defamer and now writes for Movieline.com, understands the price the Internet extracts. Lisanti thinks the axiom that cream rises to the top might not consider all the material: “It’s kind of like the golden age of art and creativity because you have access to so much more stuff, but it’s harder to find it.”

Not only that, everyone has the same idea at the same time, so there’s a rush to the finish line. As Clark points out, “Things will happen in the news, and the next day there will be a viral sketch video. Maybe 100 people have the same idea and it’s a race to get there first because you live in a world where things happen in nanoseconds.” How does one stand out then? According to Mohan, “It’s going to be the depth by which people are really willing to bare their souls . . . that’s eventually going to separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Despite the possibility of vertigo, even an old master like Ruscha feels exhilaration at the coming tsunami. “On the one hand, I say, wow, I got to hold on to my hat, because there’s too much to grasp on to, too much to try to see, and I’ve only got two eyes, and so much time. But at the same time, all these people stabbing at this thing called art -- I mean, they’re turning over rocks and finding little animals and finding little great things under these rocks. It’s just bewildering and it’s inspiring at the same time.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.