Lincoln and me

- Share via

I had never heard of the Gettysburg Address until sixth grade. All I knew of Abraham Lincoln was his majestic image enthroned on the Mall in Washington -- until Mrs. Wright introduced us to his famous speech, not as a landmark of American democracy but as a form of punishment.

As far as I knew, Mrs. Wright had taught sixth grade forever. She was an intimidating little woman, and whenever anyone spoke out of turn, she would fix the reprobate with her eyes, raise her hand and extend her index finger toward the ceiling. Protest would only provoke the elevation of a second finger, sometimes a third or even a fourth, depending on the gravity of the crime and the energy of the denial.

Her pointed fingers signaled the number of times the offender would be obliged to copy by hand the Gettysburg Address. Before I made it to the seventh grade, I must have written more than 100 “Gettysburgs,” as we used to call them, in the looping, cursive style that Mrs. Wright required.

“Four score and seven years ago ...”

It was just 10 sentences, 272 words, many of them strange and unfathomable. I had no idea what the speech meant. Looking back, it seems almost perverse -- to punish a kid with the Gettysburg Address -- but when you’re 12, what do you know? I acquiesced to classroom justice, and I wasn’t the only one. In time, Mrs. Wright had assigned so many Gettysburgs to so many kids that a kind of black-market trade in Gettysburgs developed. You could buy one Gettysburg for a nickel, three for a dime, six for a quarter.

”... testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure ...”

I remember how a friend of mine scrawled as many as he could on a single sheet of paper -- across the side, top and bottom margins, anywhere there was space. It was only toward the end of the school year that I realized that I was a dupe and a grind. Though I would write the entire speech -- each and every word -- I discovered that my friends had been skipping words, sometimes even entire sentences: “conceived liberty dedicated equal.” Mrs. Wright wasn’t reading these Gettysburgs at all. Of course not.

But I diligently plugged on.

“The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.”

Every time I came to that sentence, I paused and remarked to myself on its irony, although I didn’t call it that then. All I knew was that I had no idea “what they did here,” but my teacher hadn’t forgotten what had been said there, nor would I.

That the battle of Gettysburg was the bloodiest of the Civil War -- some 50,000 casualties -- and its ferocious turning point meant nothing to me, nor that afterward Lincoln consecrated and hallowed that ground by redefining the American democratic experiment in a speech so fine in its calibrations that it took him only three minutes.

”... that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion ...”

The wrong kind of schooling -- and I had plenty of it -- can tame the most provocative words, pacify them, render them useless. But somehow Lincoln’s words transcended the punitive, mind-numbing repetition I was subjected to, just as Lincoln himself has escaped the incessant commercialization of popular culture. In spite of the relentless trivialization, he remains more than the name on the bank, the car, the logs, the new housing development.

”... that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

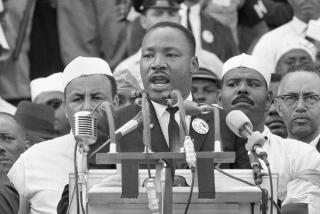

Lincoln and his Gettysburg Address rise above it all. No matter how many times it was inflicted on me, the cadences sing in my blood today. And so, in the 200th year after Lincoln’s birth, when Barack Obama took as the theme of his inauguration “a new birth of freedom,” I thrilled to the relevance of those words and the poetry of Abraham Lincoln.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.