Flagstaff, moon-adjacent

- Share via

FLAGSTAFF, ARIZ. — Astride their off-road vehicles, two teenagers are oblivious to the history over which their knobby tires are racing.

Carl Calabrese and Colin Fanelli have brought two quads and a dirt bike to the Coconino National Forest in northern Arizona to let off some steam -- and kick up some dust -- before beginning their senior year at a Phoenix-area high school.

“It’s great for riding,” Calabrese says. “It’s not congested, and there’s a bunch of jumps and stuff.” Just watch out for the giant potholes, he says.

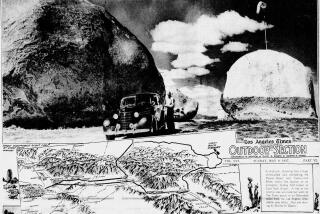

The vast field of cinders, just a few miles northeast of Flagstaff, is pockmarked with holes of varying sizes. Some are remnants of the area’s long-dormant volcanoes, but others are man-made. Explosives experts created them in the ‘60s to replicate the surface of the moon as a training ground for the Apollo astronauts.

Well before setting foot on the moon 40 years ago Monday, Neil Armstrong and his fellow Apollo 11 astronauts prepared for their mission in and around Flagstaff, an area rich in connections to that momentous “one small step for man.”

“People always ask me, ‘Why Flagstaff?’ ” says Gerry Schaber, a retired astrogeologist, during a lecture he’s giving at the Lowell Observatory to mark the 40th anniversary of the lunar landing. The answer involves three locations, all of which can be visited by people wanting to learn more about northern Arizona’s important contributions to the space race.

Schaber says the groundwork began in 1960, when Air Force scientists began mapping the lunar surface at the Lowell Observatory, which sits atop a mesa overlooking the city.

“Just like when you travel to a foreign country, you . . . better have a map,” says Kevin Schindler, the observatory’s outreach manager. Given the inability to accurately photograph the entire surface, artists with airbrushes hand-painted the lunar maps, using information that was supplied by observers who spent countless hours staring through the eyepiece of a giant telescope. Several astronauts, Armstrong among them, have peered through the same scope.

“When one of the astronauts looked at the moon through the telescope, he said, ‘Oh, so that’s where we’re going,’ ” Schindler says, sharing an anecdote from before he was born.

Lowell Observatory had secured its place in the history books well before the astronauts’ arrival. Among its many successes is the discovery of Pluto in 1930. Guided by scientists, visitors are welcome to look through the massive telescope at night. There’s also a small museum, where guests can see the original moon maps as well as a guest book signed by Armstrong in 1963.

That same year, the U.S. Geological Survey moved its Astrogeology Science Center (from Menlo Park, in the Bay Area) to Flagstaff. It was here that Schaber and others planned more than 200 field trips to train Apollo astronauts. To prepare, geologists repeatedly traversed all 21 square miles of the crater-studded cinder field that’s now a recreational spot, the Cinder Hills off-highway vehicle area. To add authenticity, Schaber says some of his colleagues donned spacesuits from earlier NASA missions, suits that obviously weren’t designed for use here on Earth.

“Some of these guys would lose 18 pounds a day,” he recalls. “The sweat would pour out of their boots like water when they took them off.”

The astrogeologist also proudly shares the story of the development of a lunar rover training vehicle in Flagstaff. Since it was a ground rover, it was nicknamed Grover.

NASA had already paid Boeing $1.5 million to build a ground rover, but Schaber says it repeatedly broke down during test runs. That’s when he enlisted the help of some local machinists to build Grover. They assembled it using a mere $1,900 in parts. The training vehicle now sits in the lobby of the USGS Flagstaff facility.

Besides the “Why Flagstaff” question, Schaber says, visitors usually have another query, thanks to conspiracy theorists: Were the lunar landings faked?

In his anniversary speech, Schaber goes to great lengths to debunk the notion that Hollywood types filmed fake missions in Arizona. One by one, he refutes the skeptics’ claims, presenting scientific evidence that, he says, proves that Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin did, indeed, walk on the moon.

Schaber then succinctly puts the myth to rest.

“That’s a bunch of bull,” he says.

--

--

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

If you go

CINDER HILLS OFF-HIGHWAY VEHICLE AREA

in the Coconino National Forest is off U.S. 89 a few miles north of Flagstaff. It is accessible only by an unpaved forest road. High-clearance vehicles are recommended.

More information: Available from the Peaks Ranger Station, 5075 N. Highway 89, in Flagstaff; (928) 526-0866.

THE LOWELL OBSERVATORY

Visitors are welcome year round. Separate admission fees apply for day and evening activities; (928) 233-3211, www.lowell.edu.

USGS SCIENCE CENTER

There’s no charge to see the ground rover (Grover) at the science center; arizona.usgs.gov/Flagstaff.

More information: The Flagstaff Visitor Center is inside the city’s old train station, 1 E. Route 66; (800) 842-7293, www.flagstaffarizona.org.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.