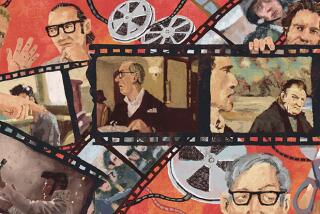

‘Five Easy Pieces’ turns 40

- Share via

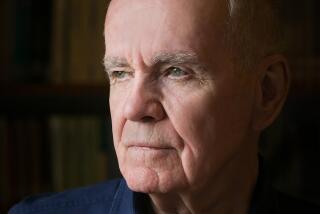

“You don’t sit down and say, ‘I’m feeling alienated today, I think I’ll make a movie about alienation,’ ” notes director Bob Rafelson, reflecting on a movie about … alienation, of all things, that he made 40 years ago.

“Five Easy Pieces,” which opens Friday at the Nuart Theatre for a weeklong run in a beautifully restored new print, gave 1970 audiences an insight not just into an America that was tearing itself apart from within, it gave them a perfect antihero for those times. Bobby Dupea is a thoroughly discontented scion of the upper classes who has willfully remade himself as an aimless oil-rig worker whose biggest pleasures in life come from either sneering or kicking at whatever’s in front of him at any given minute. “It’s ridiculous,” Bobby rages early in the film to his ostensible buddy Elton, a new father who hosted Bobby and his girlfriend Rayete the evening before. “I’m sitting here listening to some cracker … who lives in a trailer park compare his life to mine!” And then he storms off.

Bobby is pitch-perfectly embodied, of course, by Jack Nicholson, a longtime friend and collaborator of Rafelson’s. It’s a role that helped make him a star and it was, in a sense, meant to; “Pieces,” and Dupea’s character, were conceived, at least in part, as a picture and a part that would build on the attention Nicholson had gained for his work in a key role in 1969’s seminal “Easy Rider,” which earned him a supporting actor Oscar nomination, and on which Rafelson was an uncredited producer. Bobby’s way with an arch putdown, his random explosiveness and, finally, his deep disappointment with life itself seem emotions that Nicholson was born to play. And the actor’s natural charm makes Bobby compellingly watchable even when he’s doing repellent things, such as sniping at the pregnant Rayete, played, in another star-making turn, by Karen Black.

As dark as the places “Pieces” goes are — the film is essentially the story of Bobby and Rayete’s road trip from California up to the Pacific Northwest, where Bobby will see his family and dying father for the first time in years, and create more upset in the home he left years before — Black remembers the shoot as both a life and career highlight. “We shot the movie entirely in sequence, I think,” she recalls. “So we were driving up the west coast of America doing scene after scene. And I think it’s something you can definitely feel and see in the progression of those sequences. I was in ecstasy doing it. Jack is a great, great spirit and, as an actor, impeccably honest. He won’t let himself get away with anything.”

One of the many memorable scenes of the trip — one that’s often enshrined in various career-high and/or zeitgeist-defining montages that crop up on television retrospectives and awards shows — is the infamous diner scene, in which Bobby squares off against a waitress who’s being extra-punctilious about enforcing the diner’s “No substitutions” rule. The battle of wills between the two ends with Bobby literally clearing the table and, again, storming out. The initial exhilaration of the rebellious gesture, though, gives way to a real sadness: The film is full of scenes in which none of the characters can get anything that they want, let alone need.

Asked about the film’s themes, Rafelson, who now lives in Aspen, demurs, saying, “Those are things I don’t like to answer, because the answers in abbreviation become very self-serving and nonsensical. There are answers, but they’re kind of personal, and have to do with experiences I had when I was growing up.” Rafelson came up with the story and wrote two versions before turning over his own script to Carole Eastman (who’s credited in the film as Adrien Joyce). The film wound up getting four Oscar nominations: best picture, lead actor for Nicholson, supporting actress for Black and story/screenplay.

Recalling a conversation from the shoot years ago, Black says, “Jack and I were talking about certain people, people I thought put on airs, and I was saying to him that I couldn’t see the person behind the facade. And Jack said to me, ‘Blackie, you look deeply enough, and you will find the human.’ ” One reason “Five Easy Pieces” remains so powerful is because it’s a film that, with every frame, looks deeply, trying to find the human.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.