Life catches up to skier ‘Wild Bill’ Johnson

- Share via

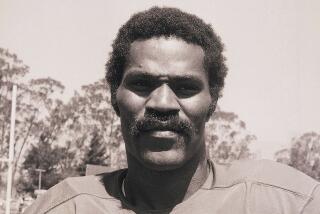

Bill Johnson was always five pounds of dynamite in a four-pound box. When he was a kid, the cops could not contain him. Oh, they’d catch him now and then -- breaking into houses or stealing a car -- but they couldn’t quell the explosive temperament. “Wild Bill,” they called him.

Downhill racing has always attracted such mad dogs and misfits -- it’s almost a job requirement. Who else but a crazy person skims down a frozen Popsicle at 90 mph? So it seems somehow prearranged that, on ice-caked vistas, Johnson would find an outlet for his lawless zeal. From the time he was 17, Johnson tore up the slopes of the Pacific Northwest. Tough as an ax handle. Bad to the bone.

By the time he was 23, the world’s best skiers couldn’t keep up with him, in spirit or in deed. At Sarajevo in 1984, he boldly predicted he would win the downhill -- and he did, becoming the first American male ever to win Olympic gold in an Alpine event.

But the world has a way of catching up with mad dogs and misfits, and such is the saga of Johnson, now 49. Half paralyzed and slow of mind and speech, he spends long days playing cards or video games in his remote Oregon trailer, tended to by a buddy who soon has to leave him and a mother who never will.

Some would argue that Johnson has made his own misfortune, but they probably don’t know the full story -- the lost savings, the failed marriage, the death of a young child.

“His success came from an inner drive and belief that most people don’t tap into,” says former teammate Phil Mahre. But “when success and fame come fast, they can often depart fast.”

In wind tunnel exercises, Johnson was “5% faster than anyone we had ever tested,” says Erik Steinberg, Johnson’s coach when he won the gold medal. “He happened to have the perfect body, where the knee caps and elbows fit together on tucks, and he happened to have these narrow shoulders that gave him a bullet shape.”

Starting in 1984, Johnson had the world by the tail and shook it every chance he got. The things he pulled on the U.S. Ski Team would make the notorious Bode Miller look like a cupcake.

“We traded flesh once or twice,” his former coach remembers. “It was like the bully on the playground. Once you stood up to him, he respected you.”

But hard as he skied, Wild Bill partied harder. After a series of disappointing finishes, he was left off the 1988 Olympic ski team. By the end of the decade, six years after his gold-medal moment, his career was all but shot.

Then life got worse. His 1-year-old son drowned in a backyard accident in 1992 and, though he and his wife, Gina, would have two more sons, the marriage would collapse in 1999. He squandered the endorsement money. At age 40, Johnson did that most-American of things -- he attempted a comeback.

“I was broke,” he explains of his longshot bid to make the 2002 Olympics at Salt Lake. “I needed to get back my wife and kids.”

Johnson’s life would be a tragedy in three acts. First, the fall from Olympic grace, then the loss of his young child, then the comeback that almost killed him.

Act III began near Whitefish, Mont., on a stretch of mountain called Corkscrew.

“I was just going fast, trying to win,” he says now. “I needed to get points.”

A horrible run it was -- a bad cocktail of inertia, impatience, metallurgy. The sound of bricks in a blender. The ax handle flew and flew, finally slamming into a fence. A 60-mph car wreck minus the car.

For three weeks, he lay in a coma -- like that toddler son had nine years earlier. Johnson would recover -- slowly and against all predictions -- enough to drive a car and ski the hills he grew up on.

But now, almost a decade later, the formerly dashing ski star is slipping again, his mind and body abandoning him, living on disability, and even then, only with constant help.

Conversations are peppered with “I don’t know” or “That’d be cool.” He often has trouble maintaining a train of thought but handles questions without complaint.

What does he do these days?

“Absolutely nothin’.”

How do you feel?

“The right side of my body doesn’t work.”

His mother, the saintly DB, worries about what will happen when her son’s buddy and roommate has to move back to Chicago very soon.

“I’m just at a loss,” says DB, 73. “He’s taken such great care of Bill.”

DB lives 20 miles east of Portland, in the foothills of Mt. Hood. Bill’s place is 30 minutes up the mountain. Because of the paralysis, it’s hard to get her son out of the house, yet they manage to see a neurosurgeon every six months.

“The good thing is that he’s in good shape otherwise,” DB says. “He’s getting a little heavy because he can’t get around so well. But the heart’s strong.”

A big fade started two years ago. Up to that point, Johnson had been able to get around, even ski, defying doctors’ predictions after the accident. But in February 2008, the head trauma seemed to catch up with him. After seven years, the brain cells began to give out. It’s as if he has lost yet another edge.

He has been in declining health since then -- the right-handed skier losing the use of his right arm and leg.

“They say that he will not recover,” DB says. “They say this is not fixable.”

In the meantime, friends staged two recent fund-raisers, in Connecticut and Vermont. The goal: to raise money for an electric scooter to help him get around, and to make Johnson’s bathroom handicapped accessible.

Twenty-six years after his biggest moment, the world has not quite forgotten the gifted skier. HBO was just out for a Bryant Gumbel segment. In a week, one of his two sons, Tyler, 15, will be visiting during a ski celebration in Portland.

So it’s chins up in the Johnson family, even as the challenges mount.

In all of sports, only motor racing has a wipeout factor that can rival the Winter Games. As you watch the skiers and the snowboarders in the next month, cross your fingers that the edges hold and the ice crystals don’t cave at the worst possible moment.

While you’re at it, say a little prayer for Bill Johnson, the once blindingly good golden boy now cooped up in his Oregon trailer, staring blankly at the cards life has left him.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.