‘Ugly Americans’: drawing partisan lines

- Share via

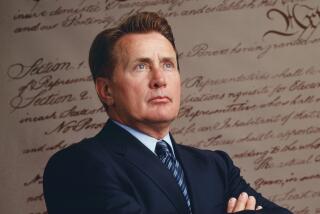

It’s not enough to be illustrated and funny anymore: These days, animation is a place for subversion and hidden meaning. It’s also the place for overt political posturing: Since “The West Wing” went off the air, liberalism and conservatism have been largely absent from television as prominent story lines or attributes. Live action television starring humans, that is. When the characters are drawn, partisan knives come out, even if the results often fizzle like ABC’s “The Goode Family.”

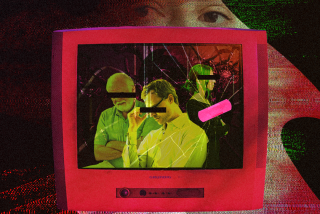

And yet this climate comes with its own oppressions: Shows begin as clever by default rather than by design. Concepts start at the outrageous and spiral outward from there. Take the animated series “Ugly Americans,” making its debut this week on Comedy Central (10:30 p.m. Wednesdays). It centers on Mark Lilly, a warm-hearted liberal social worker employed by a fictitious government agency, the Department of Integration. His job: ensuring that new citizens of all backgrounds -- ethnic, planetary, etc. -- are assimilating well into life in America.

His roommate, Randall, is a zombie, who fights the urge to gobble him up. His girlfriend, Callie, is a demon, for whom anger is an aphrodisiac. His co-workers include a wizard and a xenophobic lunkhead cop. And his charges are a motley crew of outsiders -- a two-headed man, a robot, a werewolf, a floating brain and, of course, ethnic minorities.

“It’s especially relevant in terms of today’s society -- to be young and multicultural and live in New York,” Lauren Corrao, the then head of programming at Comedy Central, told Variety last year.

Shows such as “Futurama” and “Star Trek” (in any of its incarnations), which deal with how numerous species might coexist, have always lived up to this sort of grand metaphor. But “Ugly Americans,” even though it has all the same trappings, would rather not. It’s more concerned with line, color and shading, more intriguing in art than concept. It’s alluringly drawn, and its interstitial animations have echoes of Charles Burns’ graphic novels.

But even though Mark is a do-gooder -- you can tell from the shaggy hair and the slightly loosened tie -- he’s not terribly emphatic in his views. Frank, the immigration enforcement officer, makes a far more vivid impression, delivering an electric shock to a chicken during a raid on a sweatshop and proclaiming, “Barbecue’s ready!” Or yanking a squid out of water as an interrogation technique. “Airboarding is illegal,” the squid protests.

Mark arrives to save the day in that scene, but his efforts seem half-hearted. Maybe he’s a bit of a xenophobe himself. Of Callie, a tart with demonic tendencies, he says: “Our parts match up -- that’s rarer than you’d think in this city.” Meanwhile, everyone around him is content with trans-species love: Mark, the “token bleeding heart,” as he’s described, might in fact be the city’s last conservative. He’s certainly shocked when he goes to eat with Callie’s father at what appears to be a demons-only restaurant, Le Burnadine. And his embrace of other species feels obligatory, in other words, more of an indictment of liberal pluralists than an embrace of them. Mark, it turns out, isn’t the normal one in an abnormal world: He’s the odd man out.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.