Civilian ‘hacktivists’ fight terrorists online

- Share via

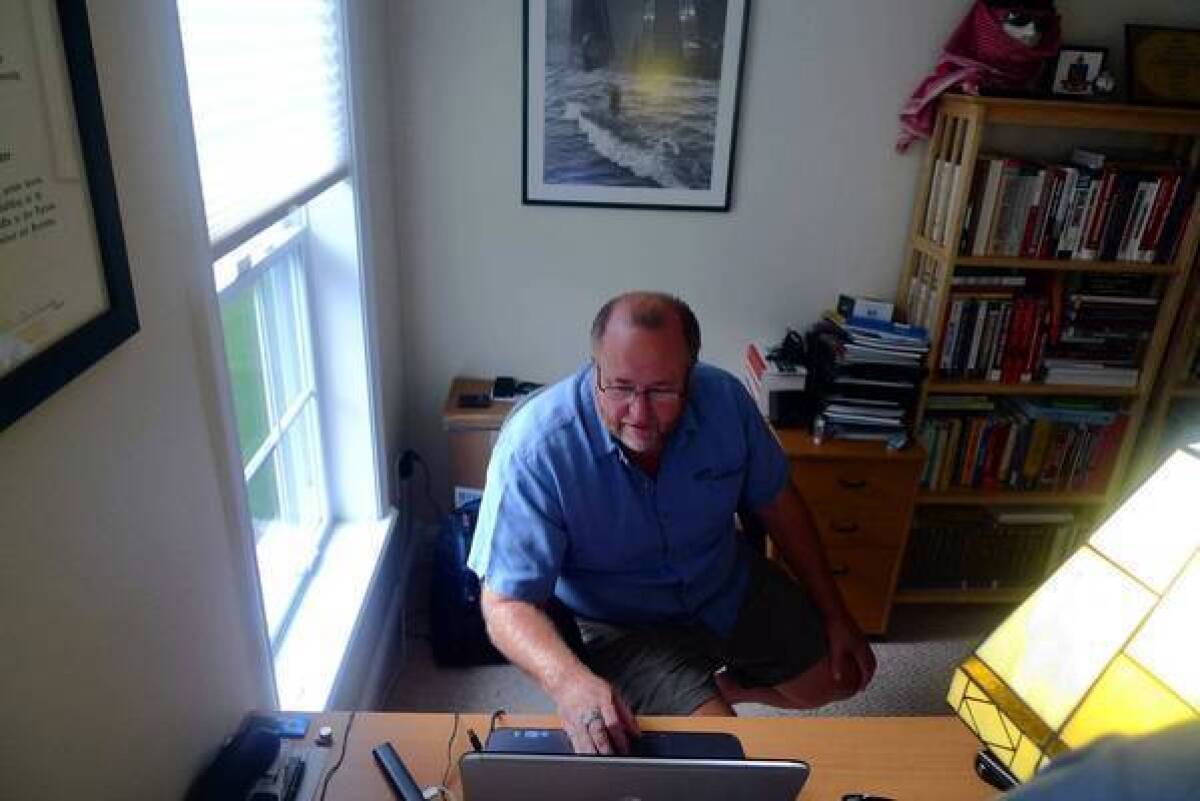

BARRE, Mass. — Working from a beige house at the end of a dirt road, Jeff Bardin switches on a laptop, boots up a program that obscures his location, and pecks in a passkey to an Internet forum run by an Iraqi branch of Al Qaeda.

Soon the screen displays battle flags and AK-47 rifles, plus palm-lined beaches to conjure up a martyr’s paradise.

“I do believe we are in,” says Bardin, a stout, 54-year-old computer security consultant.

Barefoot in his bedroom, Bardin pretends to be a 20-something Canadian who wants to train in a militant camp in Pakistan. With a few keystrokes, he begins uploading an Arabic-language manual for hand-to-hand combat to the site.

“You have to look and smell like them,” he explains. “You have to contribute to the cause so there’s trust built.”

Bardin, a former Air Force linguist who is fluent in Arabic, is part of a loose network of citizen “hacktivists” who secretly spy on Al Qaeda and its allies. Using two dozen aliases, he has penetrated chat rooms, social networking accounts and other sites where extremists seek recruits and discuss sowing mayhem.

Over the last seven years, Bardin has given the FBI and U.S. military hundreds of phone numbers and other data that he found by hacking jihadist websites. A federal law enforcement official confirmed that Bardin and a handful of other computer-savvy citizens have provided helpful information.

“This is a domain of warfare where an individual can make a difference,” Maj. T.J. O’Connor, a signal officer with Army Special Forces, told a conference in Washington, D.C., earlier this year. “Personalities are acceptable in this domain.”

But other U.S. officials worry that digital vigilantes may disrupt existing intelligence operations, spook important targets online, or shut down extremist websites that are secretly being monitored by Western agencies for fruitful tips and contacts.

“Someone needs to be the quarterback to coordinate these things,” said Frank Cilluffo, director of the Homeland Security Policy Institute at George Washington University. “If it’s not coordinated in any way, it can cause problems for the good guys.”

Cilluffo, who was special assistant for homeland security to President George W. Bush, said law enforcement and intelligence agencies are proficient at monitoring suspect websites, but are limited in their ability to disrupt them. Disabling a website hosted on U.S.-based servers is illegal.

“We need to be doing hand-to-hand combat and collection in the cyber environment,” he said.

To be sure, the super-secret National Security Agency, the largest U.S. intelligence agency, dominates digital spying and cyber-espionage overseas. The Pentagon has U.S. Cyber Command to run offensive cyberspace operations and defense of U.S. military networks. The Homeland Security Department is responsible for defending civilian networks.

And in May, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton disclosed that an obscure State Department office called the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications had hacked a Yemen-based website and replaced pro-Al Qaeda graphics with banners showing scenes of Yemeni civilians who had been killed in Al Qaeda attacks.

The office works “to preempt, discredit and outmaneuver extremist propaganda,” Clinton told a panel at the Special Operations Forces Industry Conference in Tampa, Fla.

Hacktivists view themselves as volunteers in that undeclared war. Keyboard jockeys using pseudonyms like the Jester, Raptor, and Project Vigilant have taken down dozens of jihadist forums and websites, experts say.

“No one can be 100% sure who is responsible for these attacks,” said Evan Kohlmann, a government consultant who monitors extremist websites. “We can only go with who is taking credit.”

The Jester, for example, uses a computer program he wrote called XerXes that crashes a target website by instructing it to launch continual requests for information. And his targets are not limited to jihadists.

He has claimed responsibility for the November 2010 takedown of the WikiLeaks website, which he said put national security at risk by publishing 400,000 classified U.S. military reports from Iraq. He also claims to have disabled, in February 2011, 20 websites associated with the Westboro Baptist Church, an extremist Kansas-based group known for protesting homosexuality at military funerals.

In an instant message interview using a digital encryption program, the Jester refused to give his identity. But he said he was a combat veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan now working for a telecommunications company. He said he wanted to disrupt terrorist networks, but didn’t want to work for the government.

“I feel I can be more effective overall this way,” he wrote. “Less red tape, hoops to jump thru.”

That his actions are arguably illegal doesn’t trouble him.

“If a jury of my peers were to send me too [sic] jail one day, then I can do nothing about that,” he wrote.

Bardin, the barefoot hacktivist, says he infiltrates sites only to collect information, not to sabotage or crash them. He teaches an online course at Utica College called Cyber Intelligence, and says he instructs his students to stay inside the law.

Bardin said he started entering Al Qaeda bulletin boards in 2005. Angered by online videos of beheadings and attacks on U.S. soldiers in Iraq, he wanted to strike back.

“I had to do something,” Bardin said. “I started making fake personas.”

Working with two laptops and an iPad, he has invested years developing some of his online personas. To gain the trust of website administrators, and to be granted higher levels of access, he has posted extremist material that he copies from other sites, careful to remove his own digital fingerprints.

“I don’t create new stuff,” he said. But he says “nasty things about the West” and assumes he is sometimes tracked by U.S. intelligence.

In March 2010, one of Bardin’s computer avatars was invited to Europe to help raise money for an Al Qaeda-linked group. He handed over his passwords and other details to the FBI. He doesn’t know what, if anything, was done with the information.

“It’s a one-way street,” Bardin said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.