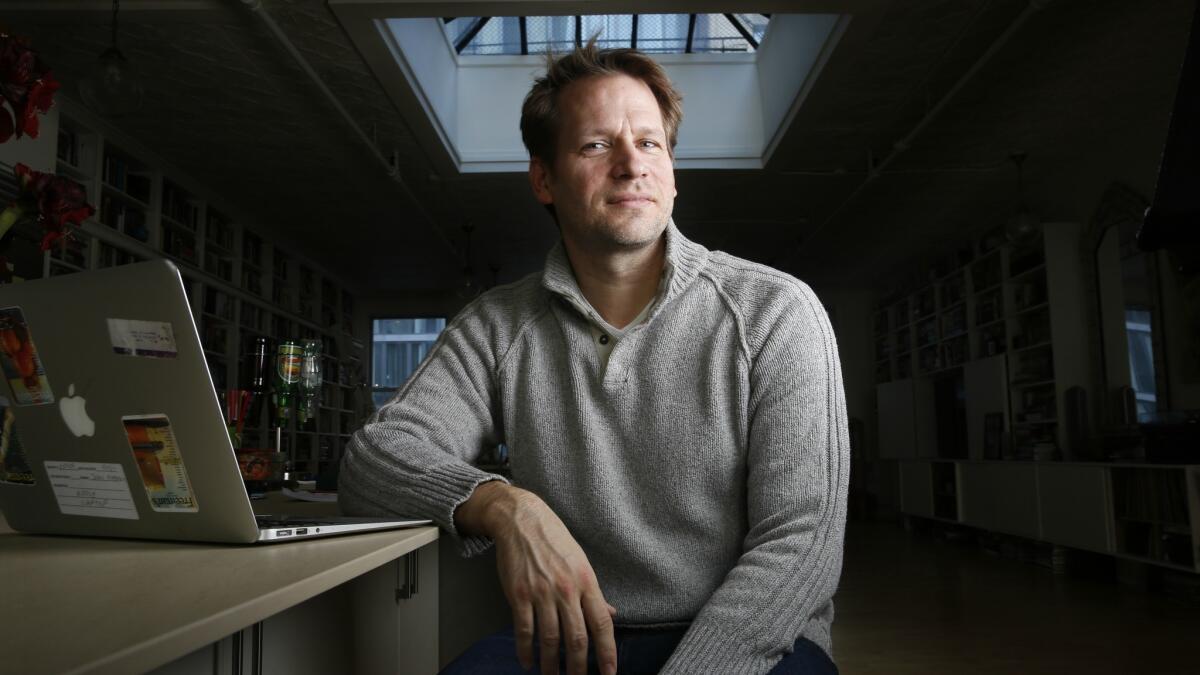

Editor John Freeman, a powerful force in the literary world

- Share via

Reporting from New York — The first time John Freeman lost his laptop, he panicked. He was traveling through Charles de Gaulle airport in summer 2016, and he only spoke “a smattering” of French. “I thought, ‘I’m never going to get this back.’ And it had three years of not-backed-up writing on it,” he recalled. Luckily, a New York University student more fluent in French was able to retrieve it, but losing the laptop three times since — at Heathrow, JFK and LaGuardia — hasn’t taught the editor, writer and critic to keep a tighter grip on his property, only to mark it more clearly. Leaning across his kitchen counter, which doubles as his desk, he points out the stickers of his contact information and the covers of his namesake literary anthology — Freeman’s.

When Freeman started Freeman’s, the journal might have seemed like the moment where he made his mark. As a former president of the National Book Critics Circle and editor of Granta, he had spent most of his career as a critic and a champion of writers, helping showcase a number of literary heavyweights. With Freeman’s, he also introduced new voices and encouraged many authors to expand their ideas beyond the pages of the journal itself. Mohsin Hamid recalls, for instance, one party conversation where the two of them made a joke about novels being a form of self-help — “and that’s where the idea for my third novel, ‘How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia,’ came from.” Publishing insiders have countless stories like this — late-night confabs, a moment of inspiration, and Freeman telling them, “Now that’s a story.” Laura Buccieri, one of his former students, refers to him as “John Freeman, story hunter.”

I think of John as one of the preeminent book people of our time

— Dave Eggers

“I think of John as one of the preeminent book people of our time,” said Dave Eggers. “He seems to know everyone, and has read every book, and reviewed most of them too. And meanwhile, he edits his magazine, and writes poetry, and apparently is some kind of semi-pro runner too. He would appear to be a hyperactive, high-intensity guy, but instead he does it all while being very low-key and unassuming. And his positivity and decency is so crucial to the health of the literary community, it’s impossible to overstate how important it is to have someone as generous and upstanding as John at the center of it all.”

Note the writing poetry comment. The poetry, after all, was what Freeman was afraid would be lost from his errant laptop — not the submissions of the countless MFA students, international discoveries and other new voices he constantly seeks out during his travels, all of which were backed up by email exchanges. “I was more worried about three-legged poems that were wandering around, looking for a home,” he said.

Freeman’s own home is a reader’s paradise — the renovated loft in the Chelsea neighborhood, at 4,000 square feet, is spacious and well lighted, thanks to a skylight. It’s lined with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, with rolling ladders stacked with even more books. (The shelves themselves were installed by literary agent Edward Orloff). Long sofas, chaises and daybeds offer multiple spots to curl up with a good book — or chat up one of many possible visiting authors, some of whom come to do business with his partner, literary agent Nicole Aragi. (She keeps a collection of fuzzy animal slippers for guests.) It’s all so cozy. Rebecca Solnit attended a December holiday shindig at chez Freeman. “I kind of felt like I was in a movie about a New York literary party,” she said. “When people fantasize about that sort of thing, this was pretty close to what they’re probably fantasizing about.”

Freeman, however, doesn’t like to stay in the comfortable zone. He sits at the kitchen counter to write, or goes to a nearby café. And the “three-legged poems” were something deeply personal, born of his need to find a way to express his grief when his mother began deteriorating from dementia. “It wasn’t like I thought, ‘Oh, now I’m going to be a poet.’ I didn’t think of myself as a writer. I just thought writing was a useful communication tool, and poetry was more direct.” His mother, Mary, eventually succumbed to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s in 2010, after a series of misdiagnoses. “Perhaps if we knew the correct diagnosis sooner, my poems would have been different,” Freeman said. “Less searching.”

Freeman’s poems “tended to be about my mom, but then they started to move sideways, and became a way of knowing her, or trying to.” Most of the poems in his first collection, “Maps,” are quietly reflective, but one in particular is full of rage: “The Money” is based on a real incident concerning the issue of inheritance. Both sets of Freeman’s grandparents were well off, but both of his parents chose to pursue careers as social workers, “where they didn’t make a lot of money.” As a consequence, Freeman grew up middle class, living in Sacramento as a youth. When he moved back to New York, he says he was only vaguely aware of the family’s wealth — his grandmother co-signed on his first apartment, but he still struggled to get by. (“My first job in publishing, I earned $20,000 a year, and I got $560 every two weeks,” he said. “My rent was $390.”) He even considered nude modeling — again. (He had earned $50 an hour posing for art classes during tough times.)

Freeman inherited some money on his mother’s death — enough to buy and renovate the loft, quit his post as editor of Granta and feel ready to start a journal of his own. But Freeman’s expanding horizons were clouded. His brother Tim’s share of the inheritance was placed in a special needs trust, and he ended up spending a year living in New York homeless shelters. “When I was 18, 19, my brother was diagnosed as a schizophrenic,” Freeman said. “And our family, it felt like we were hit by a bus, a genetic bus. I was floored by the movie ‘Donnie Darko,’ because that was finally a metaphor for what happened — the airplane engine falls out of the sky. It’s one of those things that I live with every day. I could have been like Tim. I could have had the gene that causes schizophrenia, but I don’t. It’s not like I worked hard to get it out of my system.”

Given his family history, it’s no wonder that Freeman is interested in the topic of inequality — the subject of a separate anthology series (“Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today’s New York” and “Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation”). In the first, he shared Tim’s story in his introduction, but his brother asked him not to publish it. “Then I wrote back to him and asked, ‘What if you wrote your own version, and we run that too?’” Freeman said. “I have no idea why that instinct came to me, but I’m so glad it did, because his essay’s great.”

Freeman continues to work as an editor — he’s expanded his journal digitally on LitHub, even as Grove/Atlantic plans to scale back the print schedule to once a year. And he’s planning to increase his output as a writer on topics that contextualize the way we live and how we view America, starting with a collection of essays about growing up in the West. He’s also working on an essay about the values of citizenship, engagement and action. “I don’t want to write propaganda,” he said, “but I feel like right now, we’re living in a period where it’s difficult to participate in debate or live in the public sphere. Language is being constantly vandalized, and it’s deforming what it means to be American.”

Freeman’s heart lies in the field of fiction, however. As rewarding as it is to be editing the work of writers like Haruki Murakami, Louise Erdrich, David Mitchell and Joyce Carol Oates, he still wonders if he might not have a novel of his own inside him. He did wrote one back in his 20s, actually — a “male weeper,” he says, set in the 1970s NASCAR circuit world. (It was called “The Mystery Ride of Bobby Ledew”). Unfortunately, it was rejected by four agents, which was like a dream-killer at the time. But he then met one of the agents who passed on the book — it was Aragi, in fact — and she surprised him: “Are you still writing?” she asked.

“That gave me a tiny boost,” he said, laughing. “You don’t ask that of someone whose work you hate.” The dream lives on.

Vineyard is a writer and editor in New York.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.