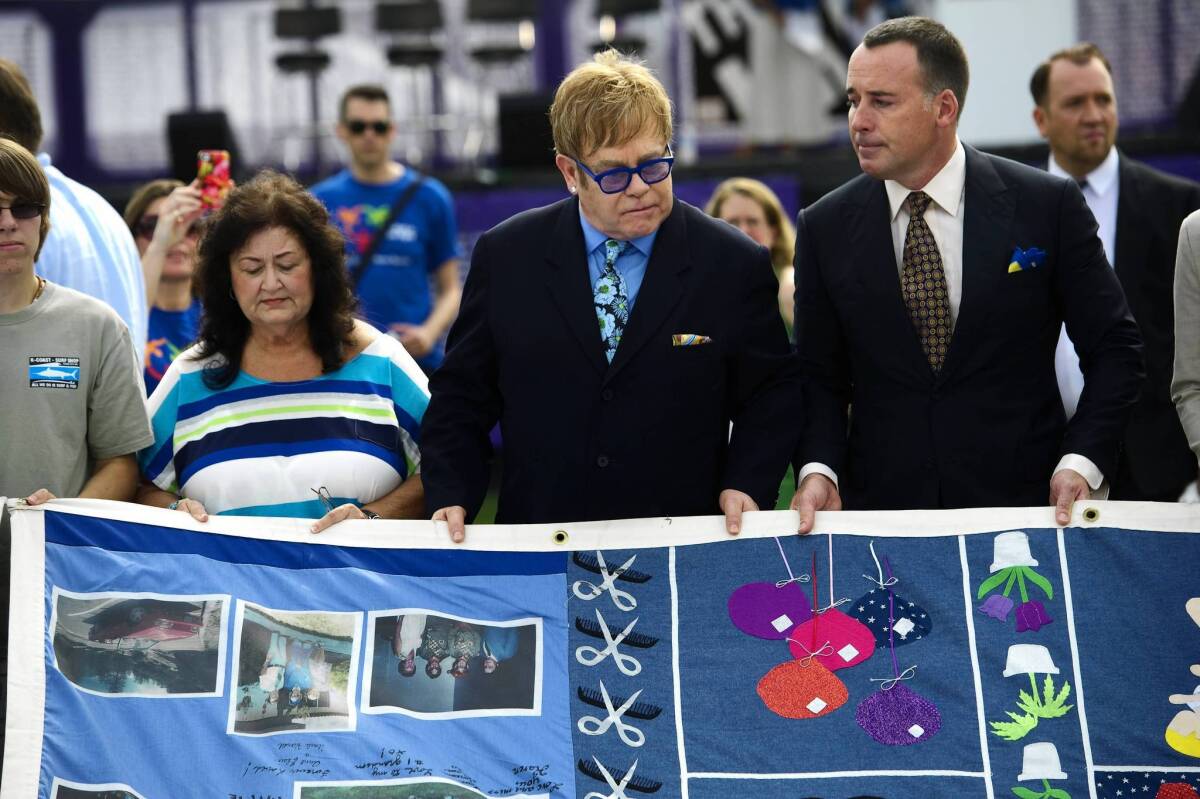

Elton John hits right notes in HIV and AIDS fight

- Share via

This past summer, in a small village outside of Phnom Penh, not far from the Mekong River, I met an 8-year-old boy named Basil. He couldn’t stop laughing, playing, racing around the village like any boy his age.

Visiting him meant something special to me because my father had met Basil too, in 2005. At the time, Basil was a tubercular baby ravaged by AIDS and abandoned by his family, with little hope for survival. Back then, infants who had gotten the disease from their mothers were 25% of the cases in Cambodia.

Now, with the widespread availability of first-line antiretroviral drugs in Cambodia, more than 80% of people living with HIV and AIDS receive treatment. The country is poised to effectively eliminate new HIV infections by 2020, partly because the government has prioritized the fight.

Meeting Basil reminded me of another boy with AIDS, one I never had the chance to meet. His name was Ryan White.

Elton John’s book, “Love Is the Cure: On Life, Loss and the End of AIDS,” newly released in paperback, opens with Ryan White’s story. The moral of Ryan and Basil’s stories are the same, but the endings are tragically different.

Ryan was infected with AIDS through a treatment for his hemophilia and driven out of school after school by ignorance, prejudice and fear. John reached out to White and his family. A friendship formed and White’s struggles inspired the creation of the Elton John AIDS Foundation 21 years ago.

What binds Basil to Ryan across continents and generations is something all too human: stigma, even against a child.

This is a disturbing theme that rings out of “Love Is the Cure”: the blunt recognition that the fight against AIDS, even today, remains a fight against indifference. The communities experiencing an increase in HIV prevalence are those on the margins of society, the people too often ignored: people who are poor, people of color, victims of trafficking, drug users, victims of abuse — groups that society, almost anywhere in the world — too often would rather look away from. The shame, as John recognizes poignantly, is not in being, it is in those who look away.

Indifference is a theme echoed in the book’s new foreword, authored by the international public health expert Dr. Paul Farmer. Farmer tells another remarkable story, this time in Rwanda, where in 1994, after a mass genocide, the nation’s health infrastructure was in tatters and thousands lived in disease-ridden refugee camps. Rwanda, he writes, had to fund hospitals and medicine, yes. But the real breakthrough came because the government faced down prejudice.

“Rwanda’s rebirth,” Farmer writes, “has come to pass most of all … because some of Rwanda’s leaders, including its health minister, have joined civil society groups to fight discrimination with legal remedies, with activism, and with an effort to realize the right to care.”

Shame, prejudice, homophobia and sexism all fuel the stigma of AIDS in developing and developed countries alike. As John describes his own reckoning with the new faces of the global AIDS pandemic through travels for his foundation, he makes it clear that these matters are both personal and political.

Yes, the politics of election years — but equally the politics of communities, of neighborhoods, of families. John’s journey is often about the frequent casualties of stigma — access to information (a crucial ingredient in prevention) and access to treatment, often for those who need it most. The stories in John’s book are crucial reminders that policy, progress and real change often depend on people initially overcoming indifference and confronting a challenge. And then doing the right thing.

All of which brings me back to Cambodia. In Cambodia, change has come through a seemingly obvious shift in policy: The country normalized HIV, focusing on the people with the disease, not the disease itself. One way this manifested was through treating HIV-positive pregnant women as pregnant women, not as separate, stigmatized patients. The country faced down its crisis of indifference. As a result of that and other interventions, Cambodia has seen tremendous progress in combating HIV and AIDS and eliminating mother-to-child transmission.

Change is hard. “Love Is the Cure” recognizes that. As John has said in poetry and prose, compassion is the key — for individuals, and for our global community. His book provides examples of incredible compassion — matched by economics and politics — that collectively are helping to change the trend lines of the AIDS epidemic. John could have provided a theme song but decided to do so much more: to reach out to Ryan White, to help Basil’s story have a different ending than the one that seemed inevitable when he was a baby — and to help truly end the AIDS epidemic for children and marginalized people everywhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.