Why do people keep writing about the Replacements, a band that never quite happened?

- Share via

A few months ago, I went with a couple friends to see Tommy Stinson, the former bassist of The Replacements, play an acoustic show in a backyard in Eagle Rock. It was part of the Wild Honey Foundation’s annual series of shows, benefiting the Autism Think Tank, and Stinson was touring the country with Chip Roberts as Cowboys in the Campfire, playing record stores and salons and oddball venues in cities big and small. Since it was a Sunday afternoon, many of the concertgoers had brought their small children with them, some of whom were running around on the lawn beside the stage before the show, shouting and laughing.

We took our folding chairs and I looked around. In front of me was the rock journalist and author Chris Morris. A few feet away was Peter Jesperson, who’d discovered and then went on to manage the Replacements, among other bands, and founded Twin Tone Records, thus providing me with the soundtrack to my own drunken youth. A woman I used to work with at a temp agency was a few rows up, alongside nearly every single session musician in Los Angeles, a dozen former A&R guys and 50 more people wearing Chuck Taylors, most with the new orthotic lining. There was a nice spread of pasta, salad and garlic bread you could purchase for a few bucks, if you didn’t mind eating on your lap, but the most addictive substance to be found at this particular show were the See’s Candy square lollipops, what we used to call all-day suckers, which were surely provided as a wink-and-nod to the opening band, LA club stalwarts All Day Sucker.

By the time Stinson took the stage to perform an hour’s worth of songs from his post-Replacements band Bash & Pop, the crowd was so loaded on carbs and suckers that we rushed the stage and started a swirl pit … or, well, no: we sat pleasantly and listened to the songs, clapped at the right times, hooted a bit, posted a lot of photos to Instagram and, when the set was over, picked up our folding chairs and helped clean the place up.

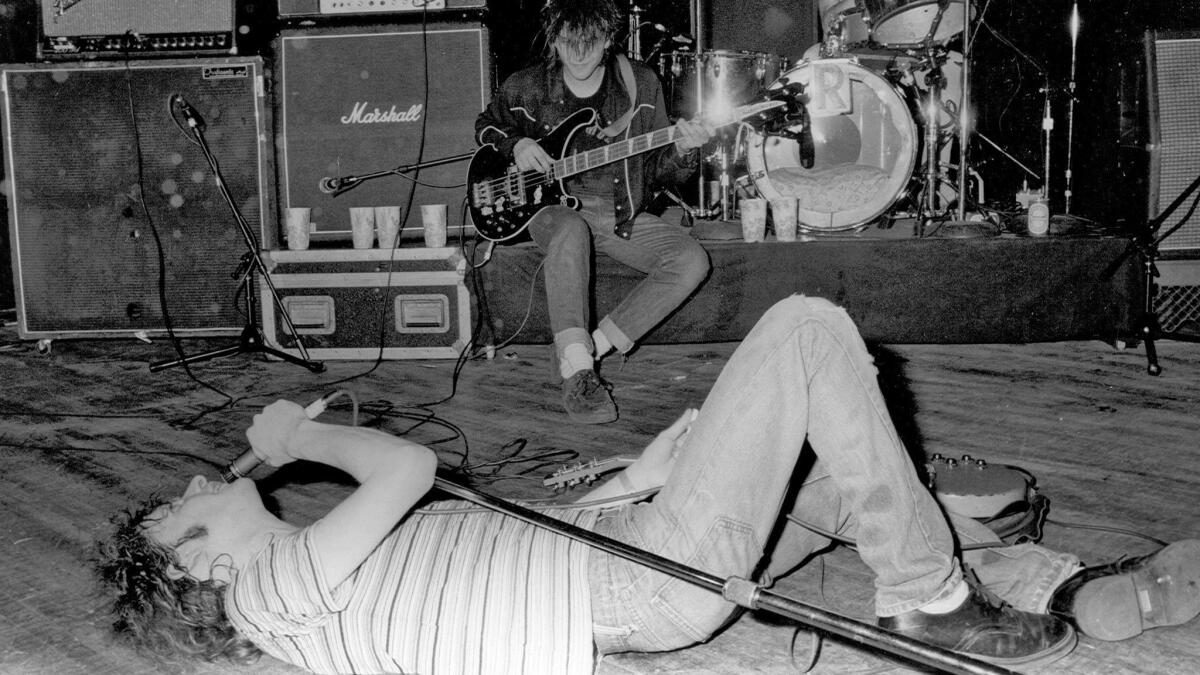

All of this stands in graphic relief to Stinson’s former life of debauchery, surely, which has once again been recounted by a third party in Bill Sullivan’s slim volume of grimy tour reminiscence and photos, “Lemon Jail: On the Road with the Replacements” (University of Minnesota Press, 160 pages, $22.95), which isn’t exactly essential reading for fans of the band as it recounts what has already been established — namely that the Replacements were comically and chemically incapable of success and no roadie, which Sullivan was, let alone manager or record label, was going to fix their propensity to destroy property, themselves and their reputations. The book does contain some wonderful black and white photography of the band in its infancy, along with a few amusing anecdotes that, as it goes on, end up being more pathetic than laugh-worthy as the beautiful losers fall apart.

“Lemon Jail” is merely the latest installment in a curious cottage industry: the continued literary parsing of a no-hit-wonder band. Writers continue to be drawn to the human failure of Tommy and his older brother, guitarist Bob Stinson, drummer Chris Mars and lead singer and songwriter Paul Westerberg — the four original members of the Replacements — nearly 30 years after their last official record, 1990’s “All Shook Down.” Bob Mehr’s exhaustive “Trouble Boys: The True Story of The Replacements,” released in 2016, is the definitive text on the band, revealing never-before known facts about the young men who formed it and also delved into the personal and business relationships that would ultimately bring the band to its knees. There are Jim Walsh’s two books, the oral history, “The Replacements: All Over But The Shouting,” and a book of photos, “The Replacements: Waxed-Up Hair and Painted Shoes.” The Decemberists’ Colin Meloy contributed a memoir of his love for the band as part of 33 1/3’s book series, focusing on the band’s 1984 record “Let It Be.” There is even a crime anthology, “Waiting To Be Forgotten,” featuring 25 mystery writers using Replacements’ songs as inspiration for their fiction. In between, a slew of other books (and even a documentary, “Color Me Obsessed”) attempt to make sense of the Replacements’ place in music history. Countless feature stories delve into the arcane: the band’s album art, the messages found in Paul Westerberg’s tour clothing, the Minnesota punk scene, the long will-they-won’t-they get back together rumors (they eventually did, touring from 2013-2015), the profiles, the remembrances, the hagiography…all of which somehow manage to use the word “shambolic” at some point. And there are the songs which reference the Replacements as a shorthand for mistakes being made, with musicians from Lucero to The Baseball Project to Ray Wylie Hubbard name-checking the band.

The four men fit nicely into some literary archetypes: Tommy, the charming kid just out for a good time; Bob, the stumbling drunk with a heart of gold and a propensity for violence; Chris, the contemplative, struggling artist; Paul, the rakish rogue. That each knew their role likely has played into the common narrative of how miserably the band ended up falling on their faces, owing primarily to rampant drug and alcohol abuse, which messed up the players but never seemed to hurt the music. In “Lemon Jail,” for instance, Sullivan recounts an incident when he found Bob Stinson had turned “blue in his bed and stopped breathing” after the hulking guitarist had overdosed on heroin. Instead of calling 911, Sullivan drags him into the shower, sprays him with cold water and slaps him a few times. When Stinson comes to, they begin fighting — until Sullivan is able to convince Stinson that he was trying to help him, that he thought the man had died.

It’s a scene of tragic-comedy, until you remember that Bob Stinson would die just a few short years later, at 35, from organ failure. And that this isn’t “Spinal Tap”: These are real people. Real people that seemed to be crying for help and receiving very little, though the question remains whether any of these young men, at the time, would have taken the help. But that’s the other thing: You probably have no idea who any of these people are, if you are the average consumer of music, which makes this industry of examination all the more odd. Take, for instance, a band like the Gin Blossoms, whose most successful album “New Miserable Experience” spent three years on the charts starting in 1992, a year after the official break-up of the Replacements, eventually selling over 5 million copies (or: about 4.5 million more than all of the the Replacements records, combined) and spawning the huge hit singles “Hey Jealousy” and “Found Out About You,” songs which took the Replacements sound and watered it down for a pop audience. “Hey Jealousy” in particular sounded so reminiscent of the Replacements it could have fit nicely on “Pleased To Meet Me,” the band’s most radio-friendly record (including the modern rock staples “Alex Chilton” and “Can’t Hardly Wait,” which later became the title of a teen movie), likely not by complete accident as both records were engineered by the late John Hampton.

The Gin Blossoms had their own tragedies — their chief songwriter killed himself not long after being kicked out of the band — to go along with their wild success, but while the Replacements are a thing of literary fascination, the Gin Blossoms just finished a turn at the San Bernardino County Fair in Victorville. In theory, people should be much more interested in the Gin Blossoms than The Replacements — on Spotify, for instance, “Hey Jealousy” has been played over 26 million times — but in fact, it seems sputtering out has made the Replacements far more interesting than succeeding ever would have. But why?

There is the artistic influence, certainly. It’s likely there would be no Nirvana or grunge in general without the Replacements. Westerberg and Co.’s freewheeling willingness to combine punk, country, swing and the blues presaged an era of popular cow punk and Americana music. The band’s best records, usually thought of as “Pleased To Meet Me” and “Let It Be,” frequently end up on lists of the best albums ever, so being the darling of critics certainly makes for interesting dinner party conversation. But it’s also possible to draw a simple literary line: It’s easier to empathize with self-sabotage than it is with wild success. Westerberg’s lyrics always hinted at what was obviously true, like on “Swingin Party,” which essentially broke down the Replacements’ chief problem: “If being afraid is a crime/Then we hang side by side.” It’s something Mehr addressed head on with Westerberg in “Trouble Boys”: “[W]hen Bob was gone,” Westerberg said, “we were scared. It was just the three of us then, and we were trying to do every kind of weird, wild thing to distract ourselves from that.” That they became a knowing cliché helps the story, I suppose, because that makes them tragic figures, not buffoons.

Sullivan, in “Lemon Jail,” sees things more romantically, which is the advantage of not having your name on the records: “I read somewhere that Paul reckoned that I got in when it was fun,” Sullivan writes, “and got out when it ceased to be fun. Sounds to me like it was only fun when I was there.” It’s a sentiment that’s found in many of the books and films about the band: That it was great fun, until it wasn’t. One doesn’t need to be Nick Carraway to know when the party is ending, but it’s not a good story if everyone leaves on time.

And it really helps if someone ends up dead.

Which is the enduring heartbreak and irony of these books about the Replacements: Bob Stinson, who founded the band, who roped in his kid brother, didn’t live to see himself turned into a literary legend, forever in Times New Roman as a drunken guitar god, which, from all accounts, he’d find repellent.

After his backyard gig in Eagle Rock, I waited in a short line to meet Tommy Stinson. I wanted to tell him that I’d gone to Minneapolis and snapped photos of myself in front of his childhood home, imagined that I was on the cover of “Let It Be,” that I’d hunted down a park bench that had been dedicated to his brother, that when I wrote my own books I listened to the little band he was in when he was a teenager, because when I need to feel joy or grief, I found it in his bass line.

But it all happened too quickly.

We shook hands, he signed a poster for me, my friend took a photo, we made some amusing conversation for half-a-moment, and then he was gone, which was good, because the kids behind me in line with their nervous parents were getting cranky and the sun was starting to set.

Goldberg’s latest novel is “Gangster Nation.” He is the director of UC Riverside’s Low Residency MFA Program in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.