Ketabsara bookstore owner Masud Valipour creates artwork from Persian poetry for Nowruz, the New Year

- Share via

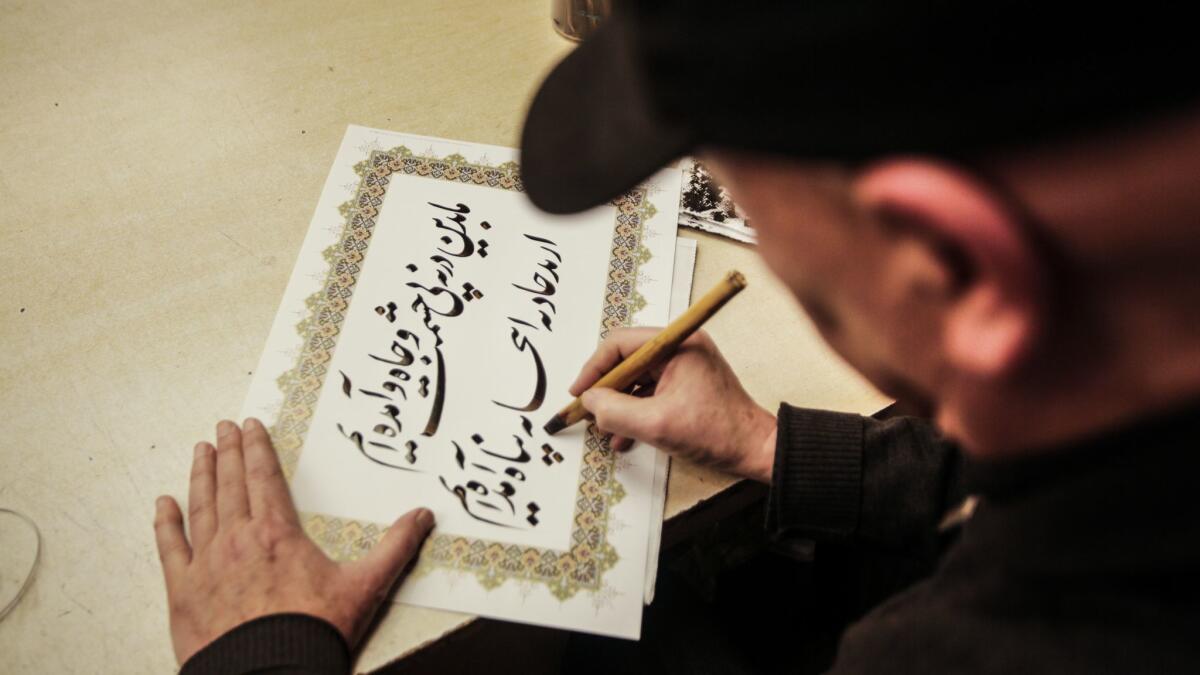

“The Farsi language is a poetic language,” says Masud Valipour, owner of Ketabsara Persian Calligraphy and Books in Westwood’s Persian Square. He gestures along the store’s walls where turquoise, jade, maroon and marigold canvases are alive with Valipour’s sweeping black calligraphy.

Ketabsara carries classic and contemporary poetry, novels and political texts in Farsi (as well as a few books in English), but Valipour’s calligraphy art of lines of Persian poetry in Farsi is the shop’s main draw.

Valipour has developed his own ornate style of the Farsi calligraphy scripts nasta’liq and shikaste, through which he seeks to embody the meaning behind a line of poetry through color, composition and artistry. He estimates that roughly 40% of his customers cannot read Farsi at all, but fluency in the language isn’t required to appreciate his calligraphy. (He includes a translation with each canvas). Even for Farsi readers it may be difficult to “read” his paintings. While the verses themselves — and their meaning — are his initial inspiration for a painting, the finished piece is something more: a way to experience poetry at a glance, to have it physically embodied, a colorful reminder on the wall.

A line by Rumi, “alas, that you are the veil upon your own treasure,” winds down a rich, golden canvas, while another, “that which is of the sea is going to the sea, it is going to the same place which it came,” washes across pure, teal blue. The text on a 40-by-90-inch painting Valipour worked on for nearly three months translates roughly to “it’s more pleasurable to journey once inside of myself than to circle 100 times around the world.” “When I say [that quote] to the Americans, they love it,” he says.

Valipour opened Ketabsara on Westwood Boulevard in 1991; he moved to Los Angeles in the late 1980s from Iran. There he owned a small book and art supply store. He devoted years to teaching himself calligraphy, particularly in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq war.

“My city was the center of the war … close to the Iraq border,” he explains. “I had nothing, almost. … [Calligraphy was] almost the only thing I had time to do.” After moving to the United States he continued to practice privately, taking the occasional order until 2001, when he began selling his work at the shop regularly.

He still accepts commissions (customers often commission him to adorn canvases with their names), but because the work he creates of his own volition bears lines by beloved, ancient Persian poets, certain standards must be met. “They say: ‘Do you take orders for anything?’ I say, ‘Not for anything.’ And they say, ‘What do you mean?’ And I say, ‘What do you mean?’” he jokes. Valipour admires Hafez and Rumi among other Persian masters and is quick to point out that while readers may associate the latter with introspective work, his “Letters” were politically engaged. “Politics is like salt,” he says – without it, life, people, even poetry, lacks flavor.

The specific lines of poetry that Valipour uses in his work all come from the same, remarkable source: his memory. How many poems does he have memorized? “Maybe thousands?” he ventures, a fraction of the couple of hundred thousand poems he estimates that he’s read over a lifetime. The store contains dozens of paintings hanging and stacked against the walls, each one bearing a unique phrase significant or moving enough to have stuck with him.

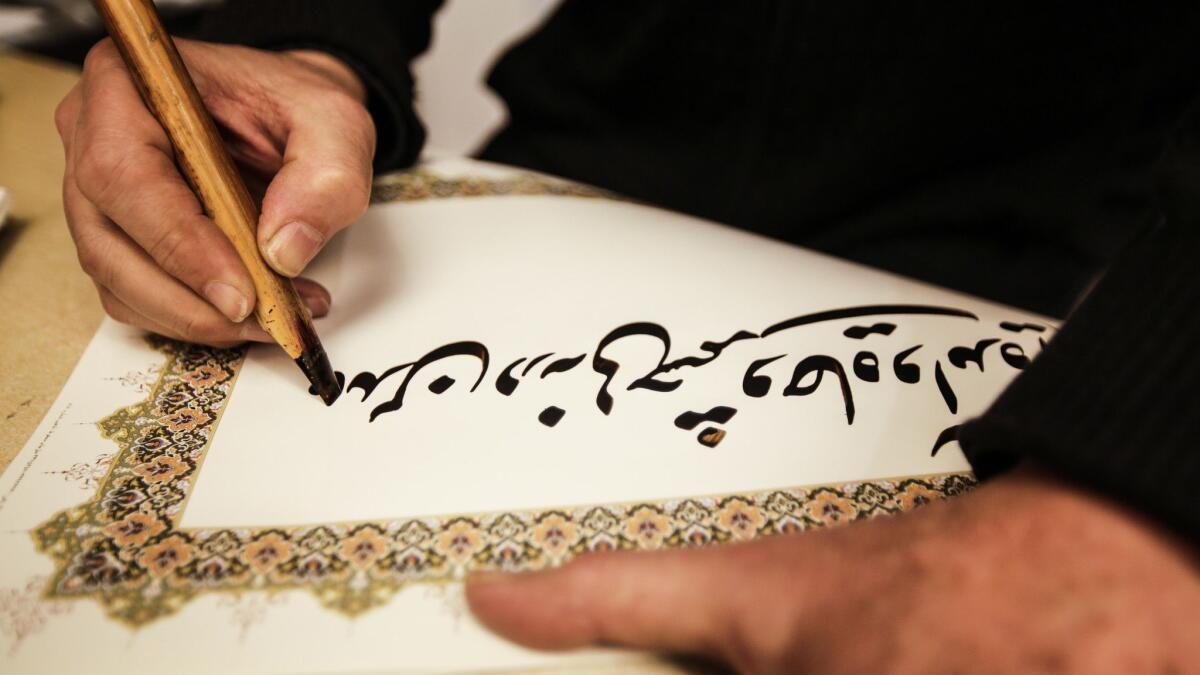

Valipour uses a bamboo reed when creating his formal work. “In Farsi we write right to left,” he explains, and yet Valipour, should the composition necessitate, may write left to right — or even upside down.

“One day a lady came in and said, ‘Hey what happened in your life that a bunch of colors and poetry and creativity came out from you?’ And I said ‘That’s a good question.’” He attributes the deepening of his approach to a moment of inspiration: the birth of his daughter. “17 years, 1 month and 11 days” ago.

Nowruz (also spelled Nerwoz or Noroz) begins on March 21. Nowruz translates to “new day” in Farsi and celebrates the arrival of spring, rebirth and renewal.

The birth of a child is the ultimate new day. No matter the poem he’s illustrating, Valipour’s calligraphy serves as a reminder. “When I started to do it, particularly on the canvas,” he says, “I started to sign my calligraphy by [my daughter’s] name.” He points to the small signature on a painting. “That’s not my name,” he says, “it’s her name.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.