Mark Sarvas’ new ‘Memento Park,’ about looted art, was ‘the book I was waiting to write’

- Share via

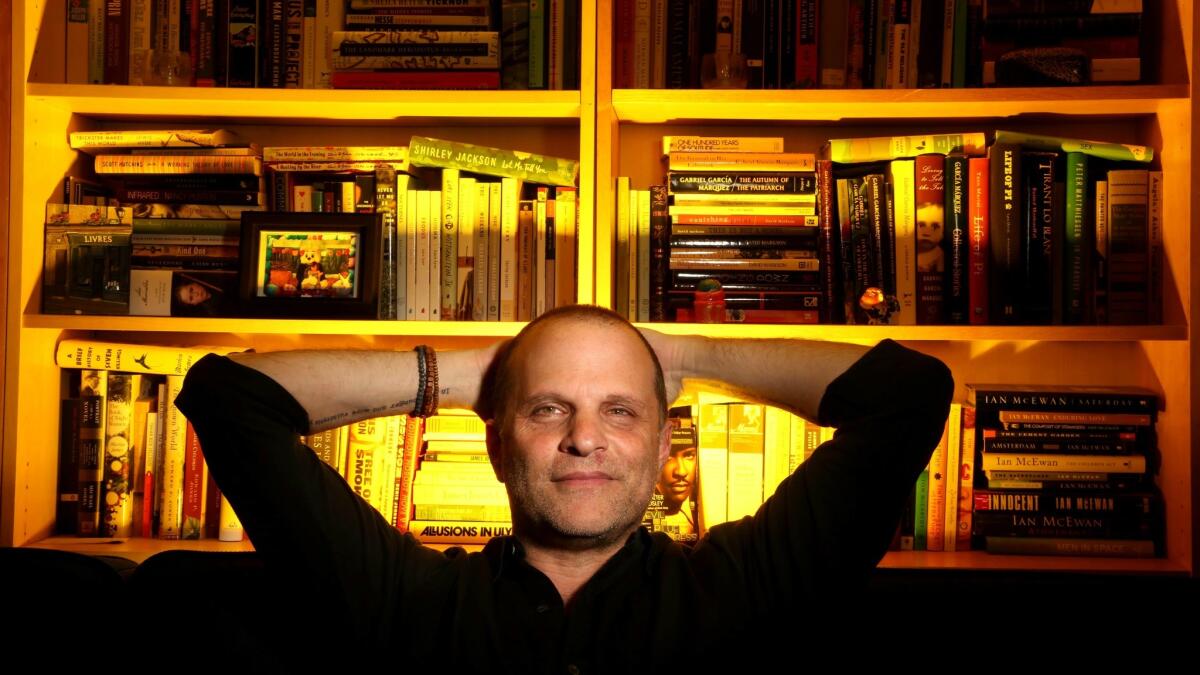

In author Mark Sarvas’ Santa Monica apartment, beside a wall of meticulously organized books, hangs a print of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s German Expressionist painting “Berlin Street Scene,” which served as the inspiration for the fictional work of art at the heart of his second novel, “Memento Park.”

The story of a second-generation Hungarian American’s attempt to reclaim that valuable painting, which may have been looted from his father’s family in Budapest during the Second World War, “Memento Park,” says Sarvas, has been a long time coming.

In the mid-’90s, when he began publishing short fiction, his bio read, “Mark is working on his first novel,” he confessed over glasses of sparkling water. The book’s subject matter? “Looted Nazi art.”

“There was a moment where I saw pretty clearly that I wanted to do more with the book than I felt able to,” said Sarvas. “So I thought, I’m going to put this in a drawer and not write it as my first book, because I’m not ready.” Instead he debuted with “Harry, Revised,” which he called his “training novel.”

“ ‘Memento Park,’ ” he said, “feels like the book I was waiting to write.” A dense, layered novel — part history, part mystery — it reckons with heritage, faith, fatherhood and the complications of confronting the past.

In conversation, Sarvas listens with a controlled, coiled energy that springs alive when he’s ready to speak or leap up to refill a glass. That quick twitch earned him fans — and foes — as the voice behind early literary blog the Elegant Variation; in a 2008 interview, The Times’ Scott Timberg described him as “acid fingered,” noting a simmering feud with fellow author Steve Almond, which Sarvas says has long been laid to rest.

“Acid fingered, bad boy blogger,” Sarvas shouldered his share of nicknames — and was happy to play the part. “People used to love getting the controversial quote out of me,” he said, a little wistfully. “It’s not that I’m being coy — I don’t feel that scathing toward people anymore.”

The experience of writing a first novel, in which “he came to realize firsthand how much a person pours into that,” softened Sarvas’ tongue. Furthermore, he became a father, and between raising a child and teaching creative writing at UCLA Extension, he’s moved away from criticism to mentorship. “Those things, they mellow you out a little. In private, with friends, over bourbons, I’ll still say stuff that’ll make your hair stand on end,” but those barbs remain behind closed doors, in part because the literary world already feels saturated with them. “In this hateful cacophony of Twitter, I don’t think it adds anything.”

“Memento Park” is written by a matured Sarvas, if not a chastened one; it’s a personal book (Sarvas is the child of Hungarian Jewish immigrants and his protagonist, Matt Santos, winkingly shares his initials) that paints Gabor Santos, the character based on his father, unflinchingly. Sarvas waited to write the novel for that reason, too.

“When I knew that my father wouldn’t be alive to see the finished book was the only time that I had the courage to sit down and start writing it,” he said. Simultaneously, “I had this awareness of losing access to a part of his past and to the story of who he was; because we didn’t get along terribly well, we weren’t super close, we didn’t have those kinds of conversations.”

The tension between examining his relationship with his father at the very moment that relationship began to slip irrevocably away became a central theme in the novel. “What happens when the past is gone forever? When you’ve waited too long to ask those questions, how do you move forward?”

One way, Sarvas discovered, is research. In the novel, Santos examines his lack of faith; to write about Judaism with authority, Sarvas took an 18-week introduction to Judaism course at the American Jewish University primarily aimed at prospective converts. “I was the only Jew in this class, and they’re all kinda looking at me like, ‘Wait a minute, you’re already in, why are you here?’ But I knew next to nothing,” he said.

Sarvas also traveled to Budapest, where he visited family, the house where his father was raised and the open-air museum strewn with Soviet-era statues from which the book borrows its title.

“You walk around these fallen warriors and it’s weirdly moving and there’s something sort of beautiful about it in spite of all the repression and the horrors that we know it represented,” he said. The trip was an effort to reconstruct the past, but it confirmed his sense that, in some ways, the past is disconcertingly present. “These things that feel like they were vestiges of another era are alive and well and very much with us,” said Sarvas.

In “Memento Park,” the quest to reclaim a stolen painting is fraught with the weight of family secrets and history. It’s a story of restitution that begs the question: Is storytelling a kind of restitution in and of itself?

“Sometimes all that’s left is the story,” said Sarvas. “I found myself thinking, maybe this character, Gabor Santos, was my father’s last gift to me.” In turn, Sarvas gives it to us — and to his family. “My daughter never knew my father,” he said, “but she’ll know him through this book.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.