The Woolsey fire destroyed a literary haven, but the stories of Brian Moore’s house remain

- Share via

Like one of those perplexing conjunctions of time and space in a Borges story, the beachfront Malibu home of Brian and Jean Moore always felt like returning to a place I had never left. I’m pretty sure those who knew and loved that house will understand what I mean, but for those who don’t, I will try to explain.

In the early ’80s, as a late-blooming, twentyish undergraduate at UCLA, I stumbled across Brian’s name on an office door while looking for my TA; spontaneously, I blundered in, and when I was done reciting the names of his novels I admired (perhaps simply to reassure us both that we existed in the same reality), I returned a few days later with several well-worn paperbacks for him to sign — “The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne,” “Fergus,” “The Doctor’s Wife.” Over the coming months and years, that single striking coincidence developed into one of the most important friendships of my life.

I took a couple of his writing workshops and produced three of my first good stories after following the one piece of advice Brian never tired of issuing to his students (and which I, in turn, have never tired of issuing to mine): “Write every day.” Later, I was invited to his home where I met his lovely and gracious wife, Jean, to whom he had dedicated every novel since the mid-’60s when they met at a party, fell in love and eventually left their respective marriages to find a new life together in Malibu — and the world. Their home was something unique in Southern California literary history — a place where local and international writers and filmmakers came to enjoy good talk and company. To my mind, Los Angeles literary culture (perhaps like many literary cultures) has often felt a bit shut away in itself; but in that lovely house, modestly presided over by Brian and Jean, there was never any sense of claustrophobia. The whole wide world was welcome.

Then, last month during the Woolsey fire, it burned to the ground.

I spent many good long nights and afternoons with them on the red-brick back patio overlooking their extensive gardens. And when I moved to London in the mid-’80s, we met up occasionally when they were in town; I published my own books and stories (every one of which reflected something I had learned from reading Brian), and even enjoyed a couple of highly productive summers as their house-sitter, writing happily away in Brian’s L-shaped office lined with books, memorabilia and photos of the life he and Jean lived together.

Over the years, that beautiful, welcoming house grew. Originally, it was a fairly small, two-bedroom beach house; but in the ’80s they built a high-ceilinged extension to the living room, along with a window-resplendent master bedroom protected by accordion-like wooden shutters. But while the house changed, its basic substance and reality never did. Every day on the back patio, hummingbirds hummed and flirted with the multitudinous seasonal flowers, and banners of pelicans drifted slowly overhead against the high currents of wind. There were the daily, ubiquitous, seal-like barks of surfers down at Leo Carrillo State Beach, and the blue Pacific that had never seemed to me to be so blue, and white bookshelves that lined almost every wall, packed with books so saturated over the decades by the alternating damp sea air and summer heat that they were turning stiff, sun-faded and brittle, often cracking down the spine when you opened them. (Brian once told me he could never bear the thought of throwing any book away, even the ones he didn’t like.)

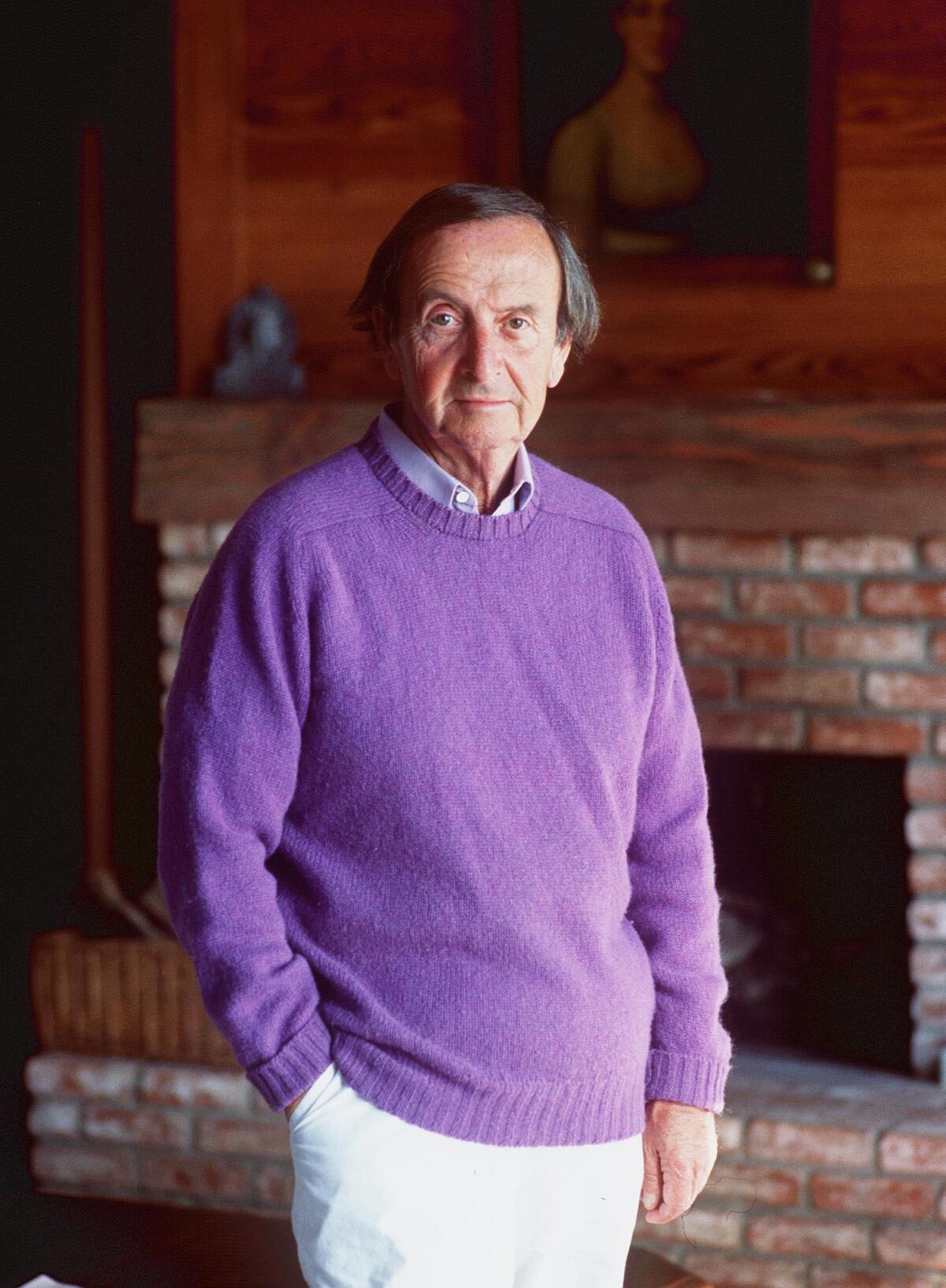

For several decades, the Moores enjoyed their happy life together: eating the meals that Jean clearly enjoyed preparing, entertaining friends, reading books and watching the world news. Every morning, Brian did what he taught his students to do: he went into his office, closed the door, and did a little writing, producing an unusual and always surprising new novel every year or two. Having written a screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock in the ’60s, he continued to write the occasional script (one for Bruce Beresford’s fine adaptation of Moore’s own novel, “Black Robe”); and well into his seventies he was still writing successful novels, including the bestselling “The Statement” (1995) and “The Magician’s Wife” in 1997. In 1994, he was awarded the L.A. Times Book Prize Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement.

Famous and celebrated people visited the Moores, such as their close friends over several decades, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, or the almost endless list of good writers, film directors and actors to whom they were devoted friends, including Julian Barnes and Pat Kavanagh, Calvin and Alice Trillin, the Irish film director Pat O’Connor and his wife, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Barry Humphries (Dame Edna Everage) and Hermione Lee.

Seamus Heaney, whose poem about visiting the Moores, “Remembering Malibu,” hung for many years in Brian’s office — later recalled the “revelation” of their “open house and hospitality, at the personal level; and intimation, at the writerly level, of withdrawal and discipline.”

As a novelist, Moore was a shape-shifter who never seemed anchored to any specific nation or historical period; he only belonged to the characters he created on the pages you couldn’t stop turning. Brian often described writing a novel as having a patient in Intensive Care. There was no point in spending all day and night with it. You could only check in every so often and make sure all the vitals were still cooking, and that no serious problems arose. And unlike the fictions of J.D. Salinger, say, or Philip Roth, Moore’s personality didn’t emanate from his books. He operated behind the scenes and, as any of his devoted readers might tell you, he took care of everything.

One of the only awkward parts of house-sitting for Brian and Jean was trying to act nonplused when I took down phone messages from the likes of Colin Firth, Natasha Richardson and Katherine Ross. But what I most loved about the Moores was the uniform interest they expressed for all their guests, even the deeply unfamous ones like myself: former students from Brian’s class at UCLA, building contractors, family and friends of family, cleaning women, manuscript typists and general handymen. For while many might initially visit their home to perform a job, they often didn’t leave until they had enjoyed a nice meal and a welcoming space where they would soon return again.

Typical conversations with Brian or Jean often included the latest news from their extended family network, such as: “You remember the cleaning lady who crashed through the front wall in her car that time? Well, her daughter just bought a new house.” Brian and Jean weren’t interested in who you knew but only in who you were. And once you knew them — if only for the length of a good conversation or a pleasant meal — you were immediately classified as someone who was. Their house always felt like coming home.

Brian died in 1999, and I dimly recall our last conversation during a pretty unhappy and chaotic period of my life. He had left a message in London on my clumsy cellphone, and when I rang back with a pocketful of change in one of those big, red, overpainted British phone booths, he told me, quite gently and surprisingly: “We are very fond of you, you know,” and I later regretted that I didn’t tell him the same thing back. At first, I thought he was simply showing support during an especially rough period I was going through, but when Jean called a few weeks later to tell me Brian had died, I realized his earlier call had been about saying goodbye. “I know how much he meant to you,” Jean told me that night, and I have always felt comfort in those words. For if Jean knew, Brian knew. It is impossible to imagine otherwise.

Jean lived on in that house for 19 years without Brian, but every time my wife Lucy and I visited, it felt like visiting them both in that house where they had lived so many good years together. We ate Jean’s excellent meals at the same candlelit table and on the same plates. And we caught up with the latest info on all the same people we had been discussing for decades. Eventually, I was even able to take my now-adult son Jack there, reintroduce him to the gardens where we wandered and played during his first summer of life, and send him off to sleep in Brian’s office, surrounded by Brian’s books. I can’t imagine a better memory for a young writer.

Over the decades, the world steadily encroached on those lovely spaces.

Even our white Westie, Mysty, who hated traveling far from her doggy bed, always ceased howling as soon as we arrived, rushing out of the car to find Jean standing at her always-welcoming front door. The last time I saw that door, in fact, was as we were departing after our last visit, two weeks before the fire. I called Mysty to the car and, like any sensible dog, she nodded goodbye, turned, and headed back into that beautiful house, where she clearly expected (like all of us) to be properly entertained.

Over the decades, the world steadily encroached on those lovely spaces. I called once or twice every year to check on Brian and Jean after the latest earthquake, brush fire, mudslide, or storm (California, to me, has always seemed rife with tiny apocalypses). At one point, the long concrete walkway down at the beach collapsed; and every year, more black ants, crickets and critters were finding their way through every crevice, until it felt as if time itself was eating into everything, while Mother Nature stood smugly by and watched.

But somehow I convinced myself that the Moores and their house were indestructible; they would weather every storm, even the death of one of them; and last month, when I began hearing daily alerts about the Woolsey fire, I didn’t call Jean right away in San Francisco, where she was staying with Brian’s son, Michael. But eventually I texted her — almost in an offhand way — and she immediately texted back: “It’s gone.” It was that sudden and that unequivocal. And if I had a hundred thousand words to describe how the loss of that house makes me feel, I don’t think I could do any better than Jean.

It’s gone.

There isn’t much else to say.

I always wanted to write about my affection for the Moores, and I’m only sorry that a horrible conflagration made me finally do it. I can’t imagine my life without Brian and Jean Moore, and the home they made for so many of us over the years.

Bradfield is a writer whose novels include “The History of Luminous Motion” and “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.