‘Ravens and Red Lipstick’ unearths an unexpected portrait over 70 years of Japanese photography

- Share via

An elongated, lumpy form seems suspended, like a flayed body twisting in the wind. One fears to find a head dangling at its tip, but the form ends in a gnarled, blackened mass instead. “Nagasaki, Bottle Melted and Deformed” was taken by Japanese photographer Tomatsu Shomei in 1961. It is both a document and a metaphor for an atomic atrocity most Americans can’t begin to comprehend.

It’s the type of image one expects to find in Lena Fritsch’s copiously illustrated “Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945.” A broad survey for Western audiences, the book also dips into less familiar territory. Both neophytes and those familiar with Japanese photography are likely to discover something unexpected.

“Ravens” includes many still life, landscape, conceptual and abstract works by the likes of Sugimoto Hiroshi, Kawauchi Rinko, Ishiuchi Miyako and others. (Fritsch respects traditional Japanese name order, last name first, throughout.) But I found myself paying particular attention to images of the body. This may reflect Fritsch’s biases: she is also the author of “The Body as a Screen: Japanese Art Photography of the 1990s.” It also likely reflects my own perspective as a Japanese American raised with a paucity of images of Asians. In suburban California in the 1970s and ’80s, Asian people appeared only occasionally in the media, and when they did (with the exception of Connie Chung), they were usually sexpots, war casualties, effeminate villains or bumbling foreigners. When you don’t see yourself in culture, you feel unimportant, then angry. Things have improved a little since then, but I am always on guard for any whiff of stereotype.

When you don’t see yourself in culture, you feel unimportant, then angry.

So I raise an eyebrow when confronted with a book like “Ravens,” in which a Western author purports to represent Japanese culture, and by extension, people.

Fritsch is curator of modern and contemporary art at Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum, a Japanese photography specialist, and a translator, but her effort comes on the heels of many egregious misrepresentations. I much appreciated her reflections on her relationship to Japanese culture, which she describes as shifting between a “‘Western’ distant position, and a ‘Japanese’ proximal perspective.” And she is careful to set “Ravens” apart from earlier publications that made overly simplistic assumptions. One author asserted that because they take their shoes off indoors, Japanese people have a “more natural relationship with the feet.” (Insert eye-roll here.) Although her references to Japanese history are often glancing, Fritsch situates her subjects within actual historical and social movements rather than reductive Western imaginings. That effort should not be remarkable, but it is.

Fritsch’s in-between position is reflected in the book’s design, which intersperses her informative, accessible history with transcriptions of 25 interviews she conducted with many of the artists. This approach allows their voices to percolate throughout, presenting varied, personal points of view. I am heartened by this mixture, and by Fritsch’s acknowledgement of her own position as a proximal outsider. The book not only provides rich, multivalent context for its arresting images, but also hope for more nuanced understandings of traditions not our own.

“Ravens” begins in the post-WWII period, in which photography served primarily as a documentary medium, recording the devastation of the war as well as the resilience of survivors. Hayashi Tadahiko’s “Orphaned street children smoking” from 1946 is a heartbreaker. Two dirty children sit on the pavement. One smokes a cigarette, the other is clothed only in a tattered breechcloth. By contrast, Domon Ken’s “Mr. and Mrs. Kotani: Survivors of the Atomic Bomb” from 1957 depicts parents and a chubby baby, smiling widely despite the scars that dapple Mr. Kotani’s face. Such images reflect a desire to look unflinchingly, but with deep humanity, at the traumas of war — the physical destruction, the abject poverty, the rending of social and familial ties — and especially the unprecedented effects of the atomic bombs. They’re a far cry from the prim studio portraiture that dominated prewar Japanese photography.

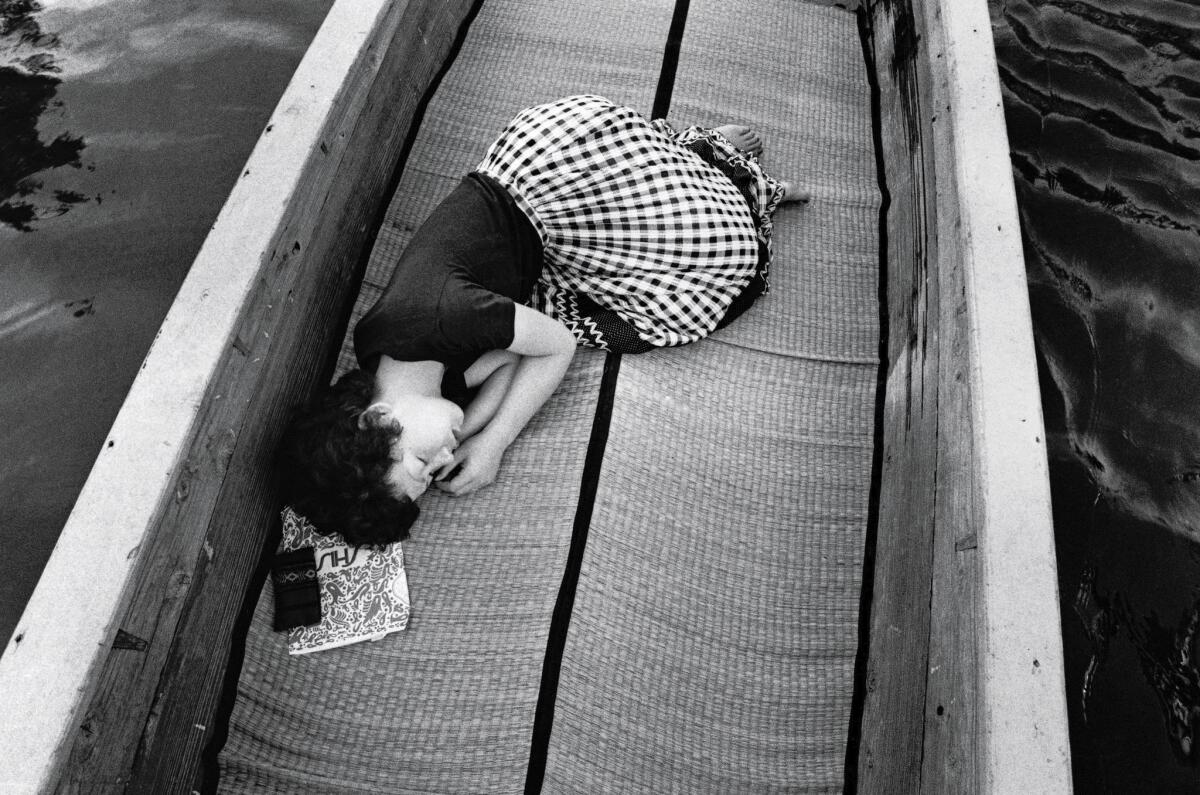

In the 1960s and ’70s, more expressive and subjective approaches emerged, most visible in the West through the work of Moriyama Daido and Araki Nobuyoshi. These photographers’ gritty, dynamic visions arose amid widespread upheavals and protests against the ongoing U.S. military presence in Japan. They were also influenced by Western photographers like William Klein who used unusual angles and out-of-focus shots to document city life.

Like Araki, Fukase Masahisa used photography in a diaristic way, often photographing his wife, Yoko, on a daily basis. When they divorced, lonesome black ravens became his dominant motif. Identifying with the stark desolation that the birds evoked, Fukase wrote that he had “become a raven with a camera.” Other artists mined Japanese folk traditions less legible in the West. Naito Masatoshi’s “Grandma Explosion (Baba Bakuhatsu)” from 1969 is an eerily surreal depiction of elderly female shamans performing a nighttime ritual dance.

From there, the book jumps ahead to 1990s “Girls’ Photography,” which emerged at the nexus of photo booth snapshots and kawaii (“cute”) culture à la Hello Kitty. As photographic technology became more accessible, young women used the medium to define themselves in the face of the male-dominated Japanese photography scene.

Still, this effort cut both ways. “Girls’ Photography” practitioners were sought after as models and entertainment figures, but this popularity made them seem more like a marketing trend than a serious artistic movement. Nagashima Yurie’s edgy self-portraits kick against this tendency. “Self-Portrait (Family #26)” from 1993 depicts her family of four in their living room in a traditional portrait pose — mother and father seated in front, children kneeling behind — all of them naked. The work is both an irreverent reworking of the family portrait and a feminist gesture that presents the body for what it is rather than for the (typically male) desires projected upon it. Works like this aligned with the girl power and riot grrrl movements that emerged internationally in the 1990s.

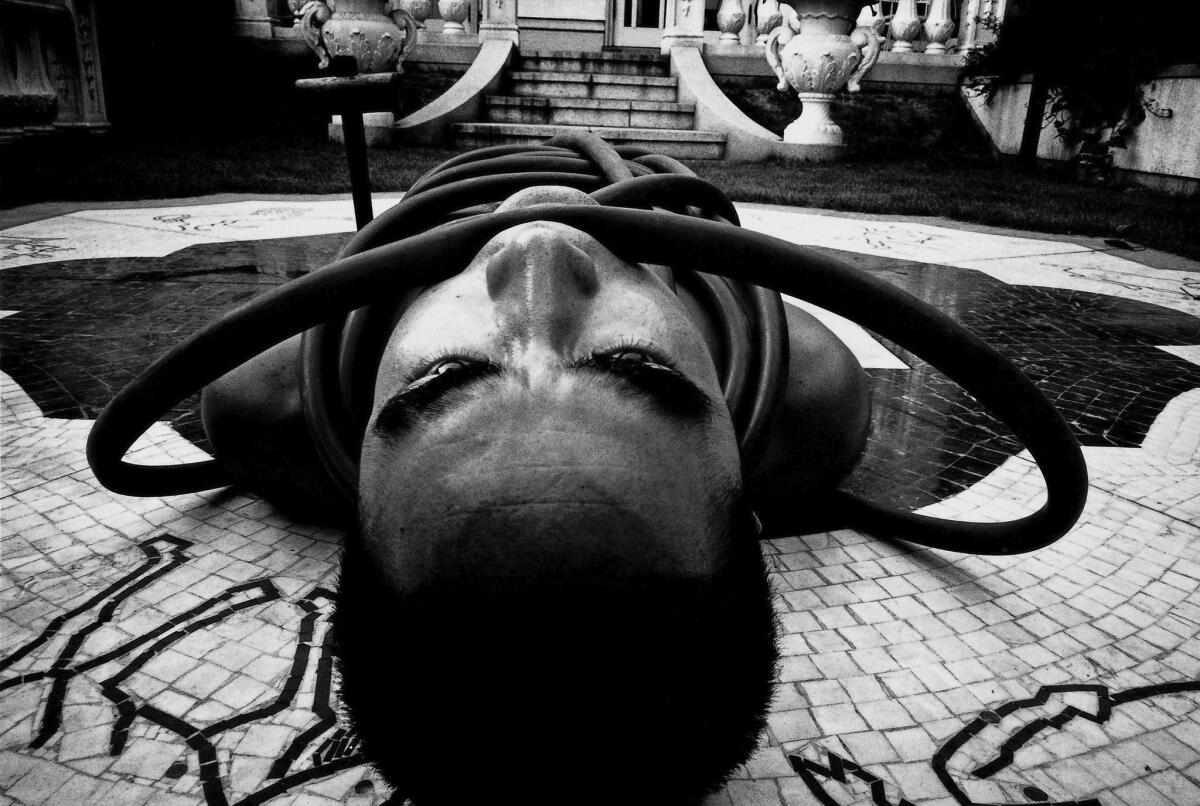

The final chapter is titled simply “Contemporary Japanese Photography” and reflects trends as varied as those found globally. One standout is Takano Ryudai’s portrait of a winsome, only partially clothed young man from 2001. The sexually charged image not only upends the dominance of the female nude, but harks back to wakashu, the faded Japanese artistic tradition of beautiful male figures, desirable to both women and men. In his interview, Takano relates how, prior to Western incursions, there was no difference between heterosexual and homosexual love in Japan. His work brings renewed attention to the male body as an object of sexual desire, reflected in the increased popularity of grooming and fashion among Japanese men in the early 2000s. However, due to a Japanese Penal Code that dates from 1907, he has often had to censor his work, cutting or covering areas where a penis is visible.

“Ravens” is refreshing because it allows these subtleties of ideation and reception to bubble up, even in a book that covers over 70 years of photography. This is due to Fritsch’s even-handed approach, one that allows for other voices and resists centering itself. I’m sure there are experts who will quibble with her choices — some artists, like Morimura Yasumasa, already much discussed in the West, receive more attention than others — but the book gives me hope. In the realm of art, at least, perhaps we are moving toward a more respectful, circumspect discourse, where it might be possible to recognize oneself through the lens of another.

::

Lena Fritsch

Thames and Hudson: 288 pp., $50

-

Sharon Mizota is an art critic and archivist whose writing appears regularly in the Los Angeles Times. She also has written for Artforum, X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, ARTNews and other publications.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.