An authoritarian leader’s shadow looms over a weary country in ‘The Remainder’

- Share via

The first sentence of “The Remainder” is also its first chapter: a taut and propulsive two pages in which the narrator, Felipe, recounts in stream-of-consciousness his attempts to make sense of the mass of corpses piling around him. He sets out for a stroll and comes across a body on a street corner (he could be hallucinating, but we think this one’s real). He bends down, lifts the stiff eyelid, and finds “a pupil that the night has clouded over, and I plunge to the depths of that socket and see myself, crystal clear, in the man’s dark iris: drowned, defeated, broken in that watery tomb …” He takes out his notepad and subtracts another body from his ledger.

“[H]ow can I square the number of dead and the number of graves?” Felipe asks, crazed, as he stares at his dim reflection. “[H]ow can I reconcile the death toll with the actual sum of the dead?” These questions form the framework for this brilliant debut by Alia Trabucco Zerán, first published in Spanish in 2015. The English translation by Sophie Hughes, which appeared in 2018 in the U.K., is truly stunning, full of deft turns of phrase, and shines especially bright when unwinding Felipe’s melodic monologues.

Felipe and Iquela, the novel’s second protagonist and alternating narrator, are childhood friends from Santiago, Chile, raised in the aftermath of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. Their parents, ex-militants, are deceased or disappeared, except for Iquela’s mother, Claudia, whose stories and memories — “a topography of her dead” — survive to plague the children. When Paloma, another daughter of the ex-militant cadre, returns to Santiago to bury her own mother, the three children, now in their 30s, find themselves on a journey as much about themselves as their country: to whom does the past belong? How does the pain of prior generations manifest? How to account for those who have vanished?

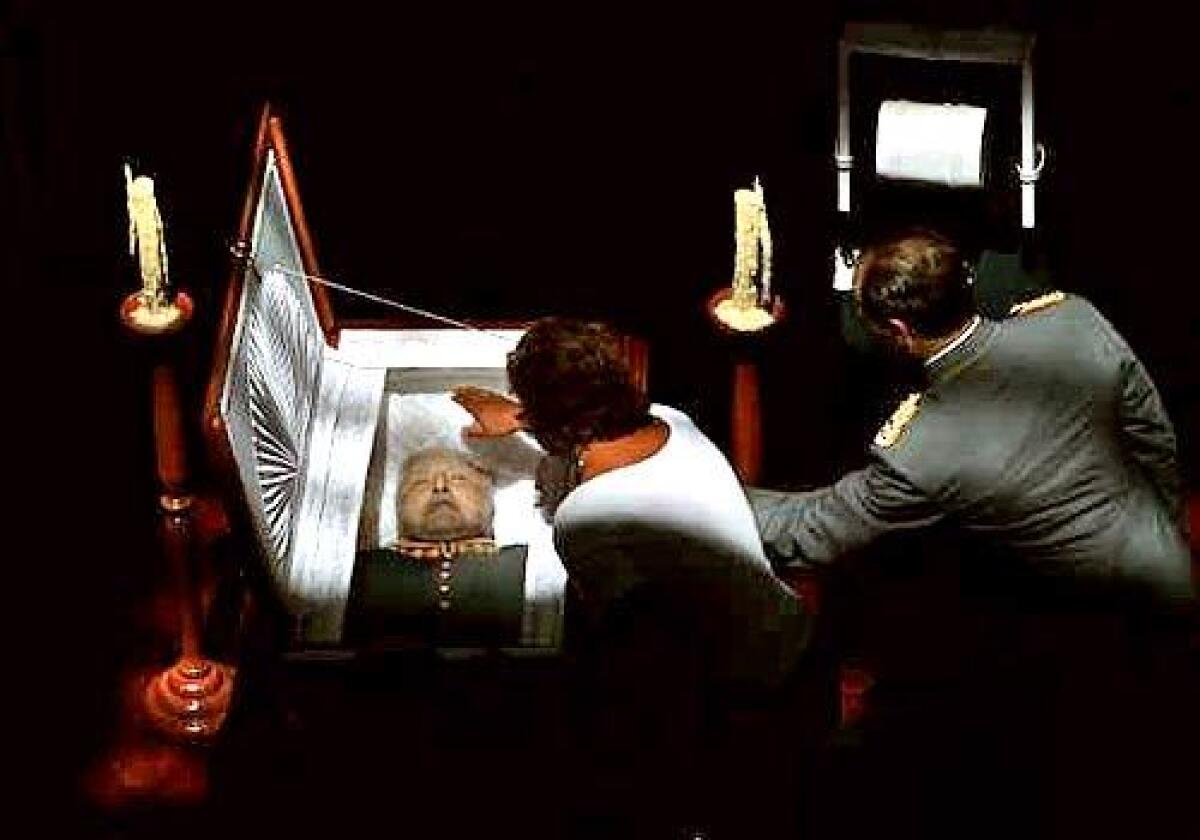

Felipe’s answer is “by deducting, tearing apart, rending bodies,” until reaching that mythical zero, a number with no remainder. Soon after Paloma arrives, the sky darkens and begins snowing ash. The plane carrying the coffin with Paloma’s mother is rerouted to Argentina, and the three rent a hearse and cross the cordillera to find her. What ensues is a sort of triple transference: as if Felipe, Iquela and Claudia could heal their old wounds, could purge the trauma in their pasts by bringing Paloma’s mother to rest.

It’s an eerie and effective way to apply pressure to the plot, and all the more so in Zerán’s hands. The exact back story that ties the families together is often left unsaid, alluded to or slowly bled from their collective memory as the tension of the road trip increases. Much of the past, in fact, is absent from the novel; Pinochet is never mentioned by name, and his fall is revealed obliquely through one of Iquela’s disturbed childhood recollections — her mother exhorting, “don’t ever forget,” while she and Paloma go around filching drinks, cigarettes and pills.

Drug use is the most standard of the methods employed to grapple with prior deaths and dislocations. Throughout “The Remainder,” Zerán masters the depiction of an almost unassuming relationship with violence. As a child, Felipe hurls himself at riptides in the ocean, nearly drowns, and emerges eager for more. He shreds his knees on homemade obstacle courses full of rocks as a “sacrificial pilgrimage.” He picks fights, collects scabs, eats the eyeball of a cow and plucks his pet bird feather by feather in apparent curiosity, then stabs it through the throat with a fork. “I thought about how there was a lot more on the inside than I imagined,” says Felipe, “things like his screeching voice, his thoughts, and each and every one of his bones, yeah, that’s what I wanted to see the most.” The impulse derives from the same vein that produces his need to make sense of “the maths,” his ongoing subtraction of bodies: something about what’s inside and outside, both for himself and his country, for those dead and those buried, still doesn’t match up.

The disjunction between the telling of such violence — written calmly, as if recounting a routine morning coffee — and the content of the acts themselves, reinforces the strange partition between past and present. This is what it feels like, Zerán suggests, for your father to be dead in a country of lost citizens. As a young girl, Iquela liked to play what she called the “scratching game.” She and a friend would spend hours lightly scratching their hands in the exact same place, “over and over, until there was no more space left under her nail, because it would be packed with flayed skin and congealed blood.” Iquela and Felipe play make-believe as each other’s grandparents, erasing the forbearers they already have. Claudia obsessively over-waters her garden and is afraid to leave her house. Paloma photographs food for a travel magazine but never eats it, instead “rearranging the meat to find an elegant — less grotesque — angle, slathering the whole plate in oil,” as if that might somehow make the meat less dead.

These compulsions are scattered across the novel, the results of Pinochet’s regime on the next generation. Iquela’s scratched hands take weeks to heal, “but at least it offered a real kind of pain,” she says, “a pain that was visible and mine.” This desire for ownership, some semblance of authentic injury independent of one’s parents and of Chile’s history, is a palpable force in the book. And yet, despite Iquela’s best efforts, she can’t quite set herself free; her mother’s stories won’t let her forget her membership in both family and country, even as she drives across the mountains in a hearse, drunk on Pisco, fleeing Santiago at last.

As the road trip progresses, certain chapters narrated by Felipe grow almost nauseating — the risk (and perhaps the purpose) his frenzied prose — but the alternating narration serves its role quite well. Iquela’s descriptions of the trio’s journey are meditative and constructed with meticulous intent. They help anchor the plot and can also be surprisingly comedic. Paired with Felipe’s fugue-like voice, the exchange in perspective becomes mimetic of the fraught reciprocations between then and now, mother and daughter, the memories of parents and those of their children.

These themes also surface in the fiction of fellow Chilean Alejandro Zambra. In his short story “Camilo,” which appears in “My Documents,” a male narrator writes from the “suspiciously stable place that is the present,” recalling the various iterations of a childhood friendship marked by intertwining father figures (one a prisoner of Pinochet). Zambra’s story — which asks, who is the father? — is less graphically harrowing than Zerán’s — which asks, where is the mother? — but equally consumed with sorting out this inheritance. Both stories and their characters offer Chile’s next generation a means to understand the horror that preceded them. For Zerán, this understanding is wrapped in a patently physical trauma: the pain of losing a corpse can only be felt in the body.

“We made a promise not to talk about it; we swore that we would forget all about it,” says Iquela, in the thrall of one such memory — not hers but her mother’s — and clearly not forgotten. “[We would] unremember anything to do with that past we hadn’t even lived through but remembered in too perfect detail for it to be made up.”

But what if both the promise and the past are too terrible to keep?

::

Alia Trabucco Zerán

Coffee House Press; 240 pp., $16.95

McCoy is a writer from Arizona and the editor of Contra Viento, a journal for art and literature from range lands. He lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.