On gun violence research, California again fills a void left by the federal government

Its Firearm Violence Research Center opened at UC Davis at the beginning of July. (July 14, 2017)

- Share via

“There’s been so little research done,” Garen J. Wintemute told me, “it’s hard to put anything at the top of the list.”

The subject was gun violence, and Wintemute’s role as head of the newest research institute of the University of California. It’s the Firearm Violence Research Center, launched in the first week of July at UC Davis, where Wintemute, 65, is a professor of emergency medicine and a nationally recognized expert in gun violence.

Wintemute has been working in this field for more than 30 years, so he’s well aware that it’s a political minefield and is equally determined to inoculate the center from political attack.

Without question, there is a very strong interest in understanding the problem of firearm violence that cuts across pro-gun and anti-gun boundaries.

— Garen Wintemute, UC Davis

“I am not an anti-gun person,” Wintemute told me. “I enjoy using the tool. But I’m not a fan of violence.”

Growing up in Long Beach, Wintemute was surrounded by weapons, including his father’s Winchester carbine and .22 rifle. Young Garen became a good shot — he once was offered a job teaching riflery — but he had no taste for training his sights on wildlife.

The center’s interest, he says, “is not in satisfying some pre-determined political agenda, but in understanding the problem so that what’s done about it is based on solid evidence and can make a difference.”

The center continues a California tradition of stepping into policy vacuums resulting from federal actions or inaction. The state created its $6-billion stem cell program in 2004 after President George W. Bush effectively ended federal funding for embryonic stem cell research. California’s vehicular fuel efficiency and emissions standards have become a model for other states and the federal government itself. And the state is poised to go it alone on climate change policy as the Trump administration becomes a haven for climate change deniers.

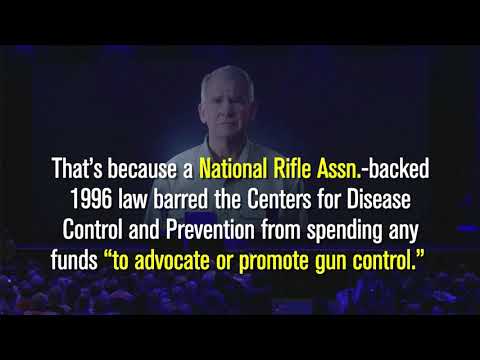

The vacuum in federally funded gun violence research dates to 1996, when Congress passed a measure by then-Rep. Jay Dickey (R-Ark.), a cat’s-paw of the National Rifle Assn., forbidding the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to spend any funds “to advocate or promote gun control.”

A succession of pusillanimous CDC directors decided that the safest course bureaucratically was simply to spend nothing at all on gun violence research — even when they were specifically ordered to reenter the field by President Obama, following the Sandy Hook Elementary massacre in 2012.

One project that faced termination with extreme prejudice post-Dickey was a Wintemute study of whether handgun buyers with prior misdemeanor records are more likely to be charged with new gun- or violence-related crimes than those without such a history.

Wintemute’s $292,000 grant was axed, though he was able to complete the work with funding from the California Wellness Foundation. (He also has contributed some $1 million in personal funds to gun violence research over the years.)

Among his findings: Handgun buyers with more than one conviction for a violent offense were more than 15 times as likely to be charged with murder, rape, robbery or aggravated assault than those with no prior criminal record.

By then, Wintemute already had roiled the firearm industry with “Ring of Fire,” a 1994 book that drew on a Wall Street Journal investigation to document the impact of six Southern California companies, mostly controlled by a single family, manufacturing the infamous Saturday Night Specials — cheap, junky handguns implicated in waves of street violence.

At one point, Wintemute recalls, Bruce Jennings, a member of the family, threatened to make his life “miserable” with lawsuits. Nothing came of the threat, in part because Jennings ended up in federal prison on a 10-year sentence for child pornography.

California’s response to the federal funding blockade was a budget rider last year establishing the Firearm Violence Research Center at UC Davis and funding it with a five-year grant of $5 million. Among the idea’s supporters was the now-retired Dickey, who has reconsidered his own legislation and co-authored a letter to state legislators endorsing the center, which he said “would help provide much-needed scientific evidence on which to base effective [violence] prevention efforts.”

Wintemute looks at gun violence research broadly, as a public health phenomenon with real socioeconomic causes and consequences. His goal is not gun control “as that term is commonly understood,” he says, but to find effective ways to prevent firearm violence.

One of the center’s initial efforts will be to assess the risk factors in gun violence. “At an individual level, those are alcohol and controlled-substance abuse and a prior history of violence. At a structural level, they’re poverty and poor education, lack of opportunity.”

Part of the task is correcting common misimpressions. The truth about public mass shootings, for example: For millions of Americans, these appallingly frequent events symbolize the nation’s gun pathology — even though, Wintemute says, “they account for less than 1% to maybe 2% of deaths from interpersonal [that is, non-suicide] firearm deaths every year.”

These events are newsworthy, however, because they can happen to anyone, anywhere, heightening anxieties about life in our public spaces.

“For large segments of the population, firearm violence occurs to people who aren’t like them and in places they know not to be,” Wintemute said. “Mass shootings happen not to people who aren’t like me, but to people just like me who are doing just the kind of things I do, wherever I happen to be.

“There’s something to learn about them that hopefully will be useful in preventing future such events.”

One possible warning sign suggested by an examination of mass shootings in California is “aberrant patterns of firearm purchases” prior to an attack, such as the rapid acquisition of lots of guns in a short period of time.

Another point Wintemute thinks needs to be understood is that “suicide is a much bigger part of firearm violence in California than people think.” According to government statistics, suicide accounted for nearly two-thirds of America’s 33,600 firearm deaths in 2014. “One of the major misconceptions about firearm violence is that it’s interpersonal. We forget that most firearm deaths are self-inflicted.”

That ties into another misconception: “People vastly overestimate the contribution that mental illness makes to homicide.” It may be an augmenting factor when other risk factors are present, such as drug or alcohol abuse, but those are the more important factors.

Mental illness plays a larger role in suicide, contributing to 45% to 75% of all suicides. It’s not schizophrenia or bipolar conditions that count, but depression, which is more common among middle-aged and elderly white males.

“Who knew that gun violence was so much an old white guy problem?” Wintemute comments.

Wintemute’s interest in firearm violence was years in the making. After spending five months in 1981 treating war victims in Cambodia after the fall of Pol Pot, he obtained a degree in public health at Johns Hopkins to go with his M.D. From then on, the issue became his life’s work. He returned to UC Davis, where he had received his medical degree, in 1983.

Despite the clear directive from the state Legislature, the center’s gestation was choppy. UC administrators tried to take control of the funds, parceling them out year by year following annual operations reviews — effectively forcing Wintemute to reapply to continue the center’s work every year.

“That set up the center to fail,” he says. Among other problems, it would be impossible to undertake long-term research projects. “We said, ‘No, thank you.’ ”

Wintemute says he wasn’t sure the center was actually going to become reality until nearly the launch date — July 1 — but UC’s Office of the President eventually relented. Even so, the president’s office will keep $150,000 a year off the top of the legislative appropriation. UC Davis, on the other hand, will contribute $100,000 a year to the center from its own budget.

In fact, the center will be a multi-campus program. Wintemute has lined up Berkeley epidemiologist Jennifer Ahern, UCI criminologist George Tita, and health educator Deborah Glik and family medicine expert Michael Rodriguez, both from UCLA, to participate in the center’s work.

The center also will function as a “micro-mini” National Institutes of Health, Wintemute says, offering small grants to researchers outside the core group. That might help to revive a field that has almost withered away in the wake of the federal moratorium.

“With almost no funding for firearm violence research, there are almost no researchers,” Wintemute reported in 2013. “Counting all academic disciplines together, no more than a dozen active, experienced investigators in the United States have focused their careers primarily on firearm violence.”

But the most important outcome may be the building of a knowledge base to inform legislators which laws and regulations work, and which don’t.

“Without question, there is a very strong interest in understanding the problem of firearm violence that cuts across pro-gun and anti-gun boundaries,” Wintemute told me. “As a society, we agree that America can do a good job confronting problems like this. But one of the first steps in doing a good job is understanding the problem.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.