Journalism’s eternal search for the outside savior, and why it fails

- Share via

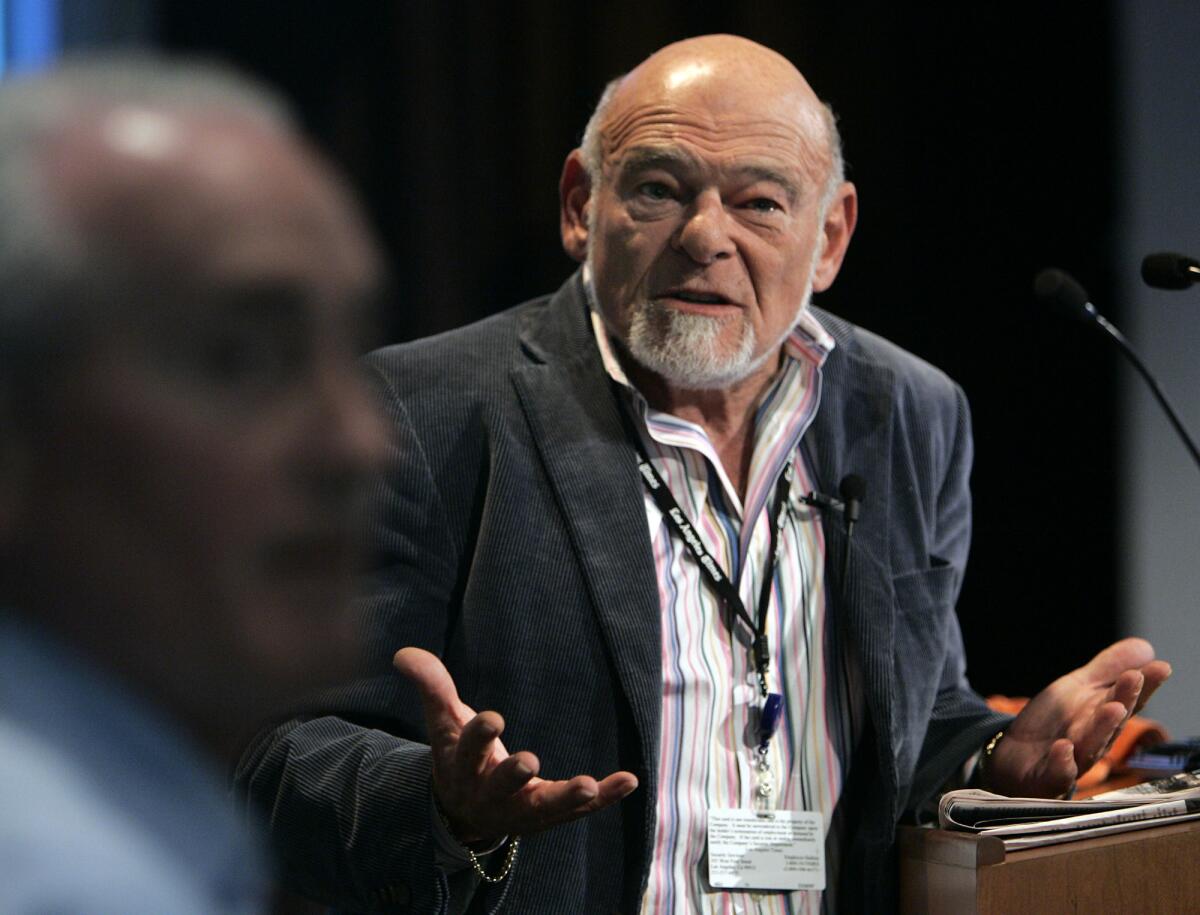

I was the first Los Angeles Times reporter to interview Sam Zell after he bought the newspaper’s parent company, Tribune, in 2007. During our interview at the executive jet terminal at LAX, he was blunt, crude and profane. He started the meeting with an extended rant about Times columnist Steve Lopez, who wasn’t present but had had the effrontery to drive up to Zell’s Malibu hideaway when he wasn’t there and do journalism by interviewing the housekeeper. But he also pledged to make the company bigger and stronger.

For the moment, I was a believer, as were many of my colleagues. We took Zell at his word that he thought of newspapers as “extraordinary brands....They’re world famous, and I just don’t think the newspaper industry as a whole has figured out how to capitalize or maximize those values.” He portrayed himself as a partner with the employees. “I’m putting $315 million in, and I don’t get any back unless you [employees] make money,” he told me.

The outcome has been well documented. Zell soon became impatient with the complexities of managing for growth a business with declining revenues. He installed a management team of surpassing crassness, and they started managing through shrinkage. The terms of Zell’s leveraged buyout left Tribune Co. hopelessly unstable, and it landed in bankruptcy in 2008, emerging only in 2012.

This pattern, in which a savior sweeps in with unbounded optimism to rescue a struggling news company, only to change course out of disillusionment and impatience, has played out over and over again. The most recent manifestation is at The New Republic, whose purported savior was the youthful and unimaginably wealthy Chris Hughes.

Hughes’ money came from his early involvement with Facebook, which happened because he was Mark Zuckerberg’s college roommate. But to read the puffery published at the time of his TNR acquisition in 2012, you would have thought he sprang full-blown from his mother’s womb as a combination of Joseph Pulitzer, Henry Ford and Napoleon. For a particularly noisome tongue-bathing, see this New York Times Magazine vignette about Hughes by ex-TNR editor Andrew Sullivan. (“I felt as if I were a kid talking with a grown-up,” wrote Sullivan, who is about two decades Hughes’ senior.)

Hughes’ claim then to “love print...because it’s an incredible technology” evaporated under the pressure of implacable losses at TNR; he’s cut its print schedule to less than once a month and now aims to convert the magazine into a “vertically integrated digital media company,” whatever that is.

He’s not alone in garnering praise for his audacity, followed by catcalls from former admirers when the dream fades. Pierre Omidyar, the billionaire founder of EBay, launched First Look Media as a new style of digital news company, staffed with such independent-minded journalists as Glenn Greenwald, with whom he pledged not to interfere. But he couldn’t resist meddling, and soon discovered that independent journalists can’t resist taking an independent approach to their bosses, too. Management of First Look was soon in disarray--as its own journalists gleefully reported--and Omidyar has sharply scaled back its ambitions.

Aaron Kushner was viewed as a savior when he bought the Orange County Register in 2012, pledging to expand the reporting staff and focus promotion on the newspaper instead of its website: An “aggressive, contrarian approach,” media analyst Ken Doctor called it, a “readers-first, invest-in-content staffing strategy.” Doctor found the approach “refreshing” and gave it, cautiously, “a chance of success.” But no; the Register is staggering financially, in part due to Kushner’s effort to launch a Los Angeles Register to compete with The Times, and his ambitions are in tatters.

Why do we keep getting taken in? Partially it’s the recognition that the economics of news-gathering are daunting in the modern age, solutions hard to come by, and the success of everything that’s been tried is still uncertain at best. The business is unique, not amenable to the turnaround strategies that work in manufacturing or retailing. So the search goes on for a magic ingredient, deployed by a rich sorcerer (Zell, Hughes, Omidyar). Is it vision? Verve? Audacity? Is it youth, or experienced age? An unlimited bank account?

Some new ventures, as well as efforts to preserve the old ones, may yet work. Vox Media and Buzzfeed are, for the moment, handsomely supported by venture investors. These investors must see something in their formula, though venture investors are by no means unerringly prescient. The Washington Post has done superb work under its new owner, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, whose wisest move may be to not interfere with its great editor, Marty Baron.

It’s proper to note that the old formula of family ownership of newspapers was far from universally dependable. During my decades as an observer and employee of family newspapers, I developed what I think of as the “three-generation rule.”

The founding generation of a news-owning family got into the business both to gain local influence and make money. (These were in the days when newspapers made lots of money.) The sons and daughters in the second generation still made money and enjoyed almost undiluted influence.

By the third generation of grandchildren and cousins, the influence became too diluted to accrue to any but one or two members. The rest were left to collect dividends. In time, they began to ask pointedly what was in it for them, since they gained no special standing in the community and were stuck earning lousier dividends than they might from investing in shopping centers or foreign currencies. Pressure to sell or break up the company would mount, and eventually the company was placed on the public market or sold privately.

This pattern underlay the Bancroft family’s sale of Dow Jones (the Wall Street Journal) to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. in 2007, and the Chandler family’s sale of Times Mirror (parent of The Times) to Tribune Co. in 2000, to be followed by Tribune’s sale to Zell. Families bailed out of local ownership all over the country. The Sulzbergers have thus far resisted the trend with the New York Times, but family pressures there are manifest.

The only sure thing is that the quest for a magic lozenge will go on. Plenty of millionaires and billionaires undoubtedly are waiting in the wings, infused with the self-image of problem-solvers, the desire to change the world as information moguls, and the thirst for lionization that comes from dictating popular opinion. And as news reporters and editors, we will keep hoping that they’ll succeed.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email mhiltzik@latimes.com.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.