What the $52-billion Cigna purchase of Express Scripts means for consumers

- Share via

The healthcare industry is consolidating in a series of head-snapping deals. But like many of the recent multibillion-dollar combinations, it’s not clear whether the just-announced $52-billion merger of Cigna Corp. and Express Scripts Holding Co. will deliver lower premiums or cheaper drugs for consumers.

On Thursday, health insurance giant Cigna announced it will buy Express Scripts, the largest pharmacy benefit manager in the country. Unless federal regulators move to block it — as they did with two recent proposed health insurance company tie-ups — the merger is expected to be complete by the end of the year.

It’s just the latest sign that healthcare giants are trying to gain more control over rising costs, especially for new prescription medicines. In December, CVS Health — a pharmacy benefit manager with almost 90 million plan members — announced it would buy Aetna, which has an estimated 45 million customers.

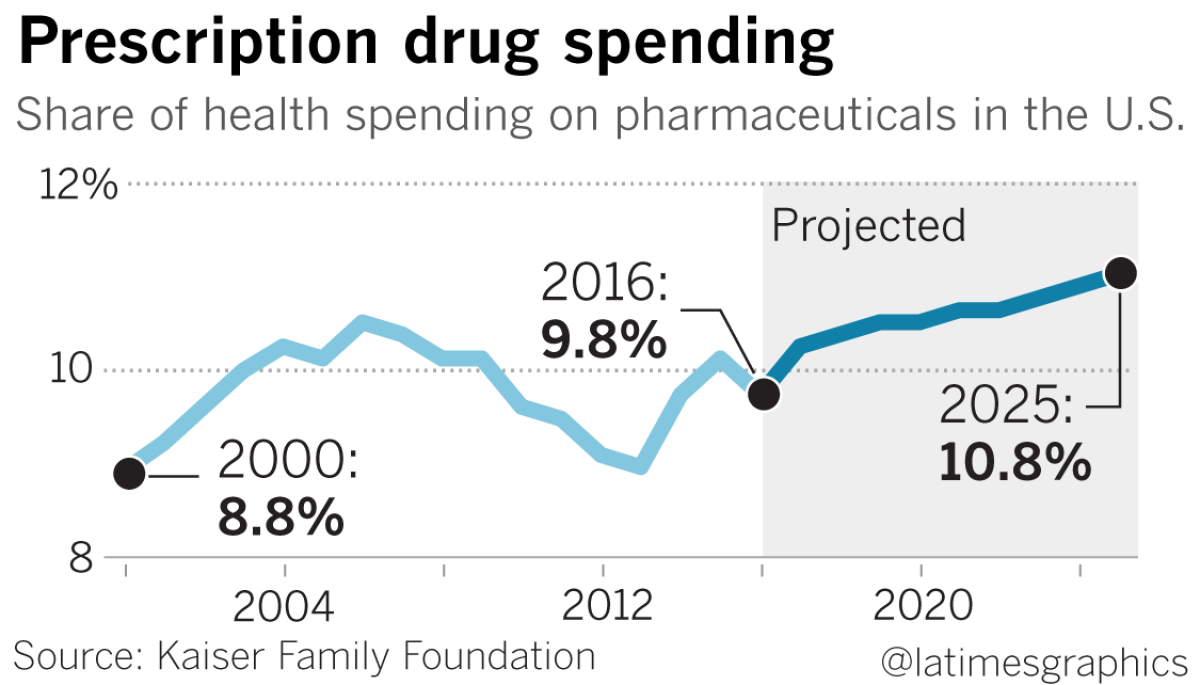

In 2015, only 1% to 2% of the American public used specialty drugs — pharmaceuticals that cost $600 or more per month — yet they accounted for about 38% of total drug expenditures. The costs of specialty drugs that older Americans commonly take increased by an average of nearly 10% between 2014 and 2015, the biggest annual increase in more than a decade, according to AARP research.

The insurers may be anticipating outside pressure, especially from Amazon.com. Last year, the retail and technology giant was reported to be interested in entering the pharmaceuticals business. And in January, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. announced a joint plan to start an independent company focused on reducing healthcare costs for their U.S. employees.

Consumers have been faced with hard choices. In a 2016 AARP survey, more than half of older Americans said they did not fill a prescription in the past two years because of cost.

Larry Levitt, senior vice president for health reform at the Kaiser Family Foundation and a former senior health policy advisor in the Clinton administration, said it is doubtful that the spate of mergers will provide relief.

“As is often the case, when one company buys another, it’s to increase earnings — helping consumers is not foremost in their minds when constructing these deals,” Levitt said. “It’s really shareholders that they’re trying to please.”

Here’s an explanation of how these companies work behind the scenes to control drug costs — and grow profits — and how that might change with mergers.

How do pharmacy benefit managers work?

In the 1960s, as Americans started taking more prescription medicines, insurance companies needed help processing those claims and began hiring pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, as third-party contractors to manage pharmacy benefit claims.

Over the past few decades, the business model for pharmacy benefit managers has evolved substantially — and with it, their sales and profits have grown. Their main job now is to work essentially as brokers between pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies, self-insured employers, union health plans and government purchasers in selecting, buying and distributing prescription drugs, according to a policy brief in Health Affairs.

For example, a pharmacy benefit manager will draft a list of approved drugs, called a formulary, for an insurance company. The pharmacy benefit manager will go to a drug company and offer to include that company’s drug on its list. In return, the drug company might agree to offer a rebate — say, $10 less on a $100 drug. The customer, however, would still pay $100, and doesn’t see any direct benefit from the rebate, Levitt said.

“Maybe down the line, that results in lower premiums — but the consumers and the employers are at the end of that line,” he said.

For every $100 spent at retail pharmacies, about $17 pays for direct production costs and $41 goes to the drug manufacturer ($15 of which is net profit). Companies that are part of the distribution system — wholesalers, pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers and insurers — get $41, splitting $8 of net profit among them, according to an analysis by USC researchers.

Drug companies set list prices for their medications, but virtually no PBM pays that price for brand-name drugs. (Someone who is uninsured very likely could pay the list price — as you could if you’re insured and have a deductible that you haven’t met.) Whether the rebates reflect great negotiating by the benefit managers or inflated drug prices is open to debate.

Some healthcare policy experts argue that this sets up a strange incentive for the benefit manager. Because they collect part of the rebate — and do not disclose publicly how much they’re getting from rebates — benefit managers stand to gain from higher list prices.

“As we’ve seen on many occasions, drug manufacturers, when left to their own devices, are capable of raising prices significantly,” Levitt said. “There needs to be some counterbalance to the drug manufacturers negotiating on behalf of consumers, and that has been pharmacy benefit managers, and they certainly do some of that. But there is a cozy relationship.”

Who are PBMs helping?

There are three pharmacy benefit managers in the United States that control most of the market: CVS Caremark, part of CVS Health, which plans to buy Aetna; Optum Rx, which is part of UnitedHealth Group; and Express Scripts, soon to be part of Cigna. In 2017, Express Scripts had revenue of $100.1 billion and net income of $4.5 billion.

Pharmacy benefit managers argue that their large size gives them bargaining power to negotiate lower prices for their clients. In early February, Express Scripts announced that it “helped employers reduce the rate of growth in per-person prescription drug spending to 1.5% in 2017,” the lowest growth rate the company has measured since 1993.

“We know many still struggle to afford their medications, and we will continue to innovate — and advocate — for those people who are challenged by their out-of-pocket costs,” Express Scripts President and Chief Executive Tim Wentworth said in a statement.

But the structure and practices of PBMs make it difficult to tell how they are helping patients and insurers, noted a 2017 analysis by researchers at the USC Schaeffer Center. “PBMs carefully guard information about the size of negotiated rebates and discounts, which may enhance their ability to negotiate lower prices, but also masks whether they are indeed lowering the prices paid by patients and insurers as claimed,” the study said.

Currently, there is no state agency that regulates PBMs. Assemblyman Jim Wood (D-Healdsburg) has a bill that would require pharmacy benefit managers to register with the California Department of Managed Health Care.

The bill would also address contractual restrictions — dubbed by opponents as “gag clauses” — that pharmacy benefit managers place on pharmacists. Those clauses mandate that a pharmacist cannot tell a patient if a drug is available cheaper if they pay cash, rather than buying it through their insurance. Even if a patient asks their pharmacist if paying in cash would be less expensive, some contracts restrict what a pharmacist can say, said Jon Roth, head of the California Pharmacists Association.

“The pharmacist wants to do the right thing for the patient ... but if the pharmacy benefit manager found out, they’d be kicked out the network,” Roth said.

So who wins in these combinations?

The fear among patient advocates is that as Cigna and Express Scripts save money through increased efficiency, they will not pass those savings along to patients but rather to their shareholders, said Ben Wakana, executive director of the group Patients for Affordable Drugs.

“To an organization that is made up of a community of patients who share stories about how they’re cutting pills in half and skipping doses and taking out credit card debt to afford prescription drugs, this merger to us looks like a corporate merger that’s more about higher profits for shareholders than it is about lower drug prices for patients,” said Wakana, who previously worked as deputy assistant public affairs secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President Obama.

For Medicare Part D enrollees, mergers could reduce their access to certain medicines. If Cigna buys Express Scripts and CVS merges with Aetna, it would give these firms an “outsized role in formulary coverage decisions in Medicare Part D” since there would be four plans in control of 86% of the stand-alone drug plan market, said Juliette Cubanski, a Medicare expert at Kaiser Family Foundation.

“As it works, pharmaceutical companies negotiate with PBMs for greater market exposure for their products by offering steeper rebates in exchange for favorable formulary placement,” Cubanski said. “The alternative is that PBMs place drugs on non-preferred tiers or don’t cover medications on their formulary at all. So as plans consolidate, they might gain bargaining power with pharmaceutical companies since they control more market share. But at the same time, if formulary options diminish, patients may have fewer options for finding coverage of the drugs they take.”

Cigna and Express Scripts in their announcement Thursday said that the merger would improve quality, affordability and choice for customers, and provide more healthcare coordination. “This combination will create significant benefit to society and differentiated shareholder value,” David M. Cordani, Cigna president and CEO, said in a statement.

Cigna rejected the idea that only shareholders will benefit from its purchase of Express Scripts. “We strongly believe the combination of Cigna, a health services company, and Express Scripts, a pharmacy services company, will drive greater affordability,” its statement read. “Both companies have proven track records of reducing healthcare costs.”

Consumers probably won’t see an immediate jump in drug prices or insurance premiums over what was coming anyway, said Gerald Kominski, director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. But they also are unlikely to reap the merger’s benefits, he said.

“This deal makes sense from a business perspective,” Kominski said. “It’s not clear it generates any noticeable improvement to consumers. I don’t think it’s harmful per se, but I will say we also worry that with more and more consolidation on the business side of healthcare, that reduces competition, and less competition is generally not good for consumers.”

UPDATES:

For the Record: An earlier version of this story said benefit managers do not disclose to anyone, including their own clients, how much they’re getting from rebates. Express Scripts said it does disclose those amounts to its clients.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.