As shoppers shift online, so do Southern California jobs

- Share via

After more than five decades selling women’s clothing, Limited Stores Co. filed for bankruptcy early this year and closed its 250 stores nationwide, including several in Southern California malls where dozens of employees lost their jobs.

Limited’s exit was part of the seismic change now occurring in retail, in which consumers’ accelerating shift to more online shopping is forcing retailers to close their physical stores.

But there’s a flip side to the tumult that was apparent three weeks later when Amazon.com Inc., the giant of e-commerce, announced plans for two more sprawling distribution centers in Southern California’s Inland Empire east of Los Angeles — generating 2,000 full-time jobs.

As shoppers increasingly move to the Internet world, so too is employment, with Southern California clearly illustrating retail’s dramatic restructuring.

Although there’s no discounting the damage done to employees as retail jobs disappear along with stores, other jobs are being created as Amazon,

“Those communities that have logistics facilities are going to see those sectors grow, simply because of the shift that’s occurred from consumers going to the store to going online,” said John Husing, chief economist of the Inland Empire Economic Partnership.

Some of those jobs also tend to pay better, Husing said.

In the first quarter of 2016, the most recent period available, the median wage in retail, restaurants and other services in the Inland Empire was $14.08 an hour, compared with $21.85 an hour in warehousing, trucking and wholesale trade, Husing said, citing state Employment Development Department data.

Wal-Mart charges ahead in an online retail market dominated by Amazon »

Many types of vacant storefronts

The retailers that have gone out of business or winnowed their store rosters in recent years — or still plan to — cover a wide range of shopping. They include department stores such as Macy’s Inc. and Sears Holding Corp., other apparel outlets such as American Apparel Inc. and Wet Seal, and sporting-goods retailers such as

The trend is continuing apace this year.

Apparel retailer Bebe Stores Inc. is closing its 168 stores, including 33 in California that employ 700 workers. Payless ShoeSource Inc. this month filed for bankruptcy protection and said it would close about 400 underperforming stores. J.C. Penney Co. plans to close 138 stores, or 14% of its total outlets, on July 31.

The chic clothing retailer BCBG Max Azria Group in Los Angeles also filed for bankruptcy reorganization and closed 120 U.S. stores this year as part of its restructuring.

Jacqueline Armendariz, 30, of South El Monte was among those caught in BCBG’s downfall. She was a technical design coordinator with the firm when she was laid off in 2015 as BCBG began downsizing, and she understands what thousands of other retail workers are now enduring.

“It’s difficult seeing people go through what I had to go through, because I remember how it affected me and it’s hard,” said Armendariz, who later found a sales position with Color Image Apparel in the City of Commerce with the help of the staffing services firm Robert Half OfficeTeam.

“We saw it coming ... the shift with shoppers moving to online clothing sites,” she said. “Everything is at your fingertips for the best price.”

Stores closing at a record pace

About 2,880 retail stores nationwide have closed so far in 2017, more than double the 1,153 closed during the same stretch in 2016, according to analyst Christian Buss of Credit Suisse.

At the current rate, “we estimate there could be more than 8,640 store closings this year, which will be higher than the historical 2008 peak of approximately 6,200 store closings” when the severe recession took hold, Buss wrote in a recent note to clients.

As a result, 29,700 retail jobs nationwide were lost in March after the industry shed 30,900 jobs in February — the largest two-month decline since 2009, the U.S. Labor Department said.

California nearly equaled the entire national drop in retail jobs in February, when statewide retail employment fell by 28,700 to 1.66 million, according to the Employment Development Department.

Part of those declines probably reflected seasonal factors; retailers aggressively hire workers for the December holidays and then let many go. And there still are pockets of growth in retail jobs in California.

Five Below Inc., a Philadelphia operator of teen-oriented specialty stores, said this month that it’s opening nine stores in Southern California — its first on the West Coast — that will create 320 jobs.

“We expect California to be our largest state for stores in the coming years,” Five Below Chief Executive Joel Anderson said in a statement.

But that’s not nearly enough to slow the growing retail job losses in Southern California that are evident in figures compiled by the EDD.

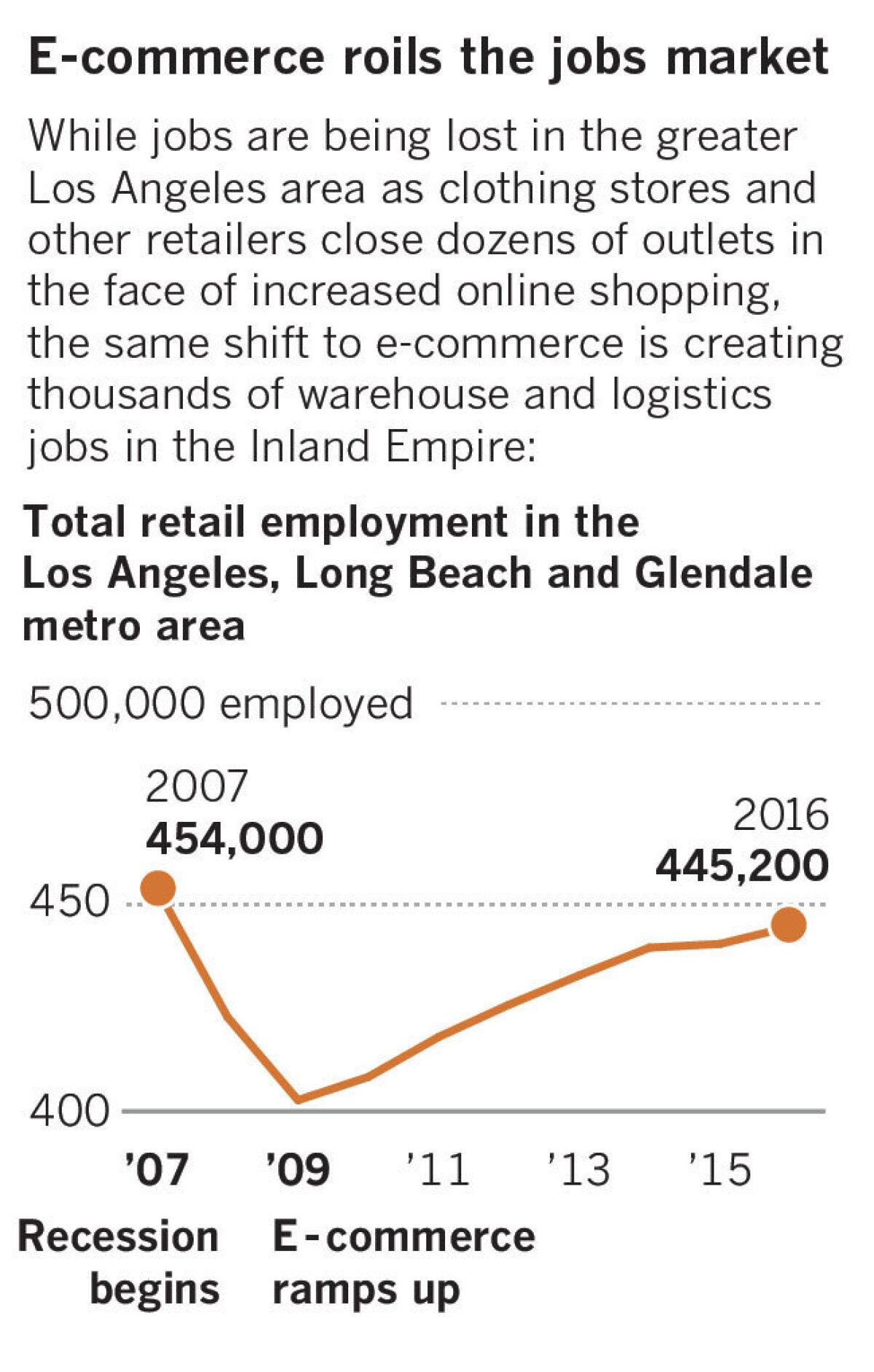

Employment at clothing and accessories stores in the Los Angeles area dropped to 57,800 at the end of last year, down from 63,200 at year-end 2007, before the recession — a loss of 5,400 jobs. In March, retail employment fell to 48,700, down 1,300 jobs from the 50,000 employed in March 2016.

Those losses have helped keep a lid on overall retail job growth in Los Angeles. Total retail employment was 445,200 at the end of 2016, below the pre-recession level of 454,400 nearly a decade ago. It dropped nearly 30,000 more jobs in the first three months of this year to 415,500 in March.

(California’s overall unemployment rate stood at 4.9% in March compared with the 4.5% rate nationwide.)

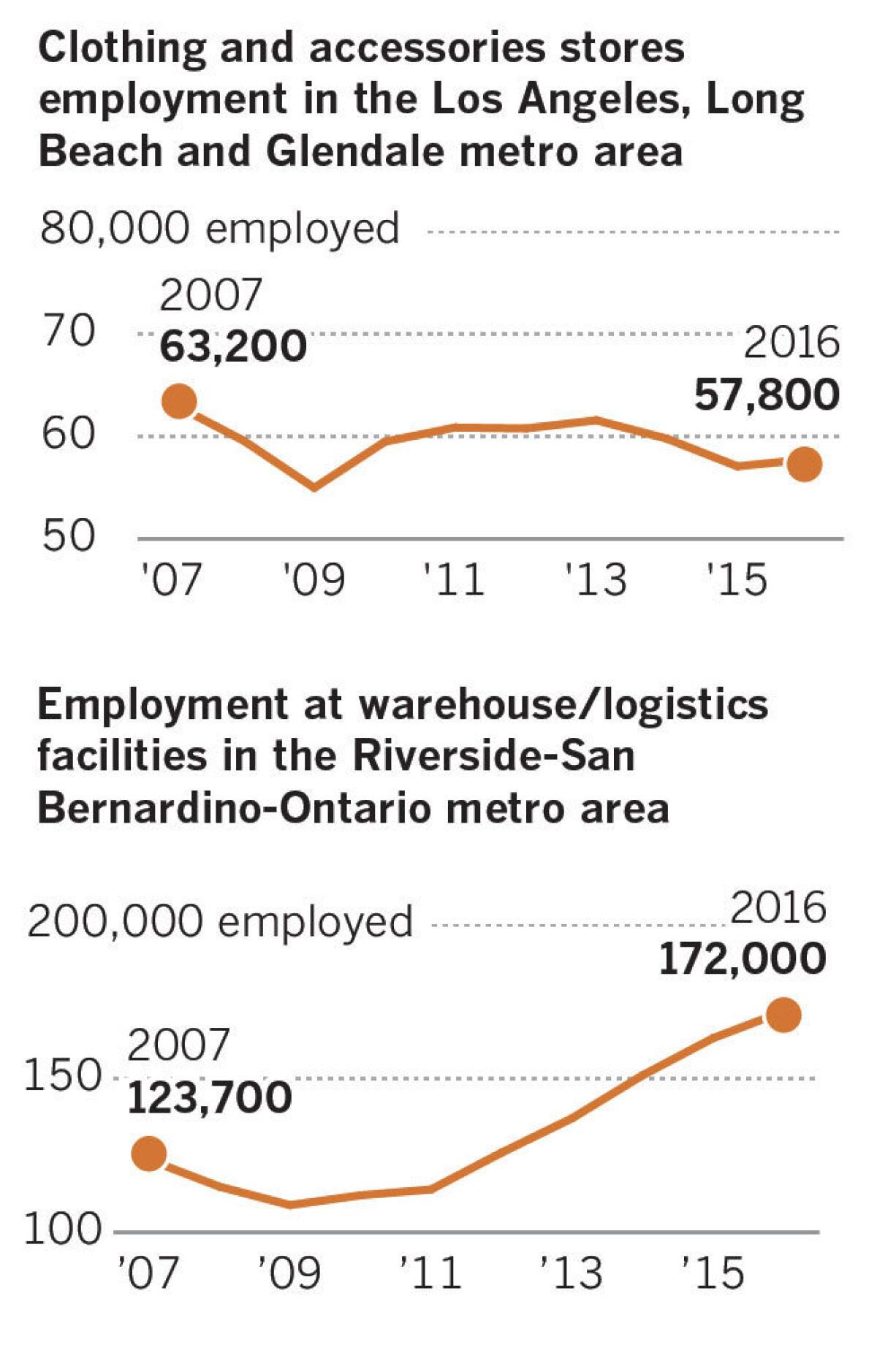

But it’s a far different story in the Inland Empire — which includes Ontario, Redlands, Riverside and San Bernardino — because of the surge in online shopping.

Employment at warehouse and logistics facilities in that region soared to 172,000 by the end of last year, a gain of 48,300 jobs since 2007, EDD figures show.

“For the Inland Empire, it’s 23% of all the job growth in this region,” Husing said.

Amazon already has five fulfillment centers in the Inland Empire and nine in California overall, employing 15,000 people who select, pack and ship the products ordered online.

Amazon’s two new centers are planned for Redlands and Eastvale near Riverside. Amazon recently began taking applications for the 1,000 jobs at the 750,000-square-foot Redlands plant.

New jobs in Redlands might be of little consolation to someone who lost a retail job in Hollywood or Santa Ana and can’t commute to the Inland Empire even if work is available.

Amazon and other warehouse operators also have critics who contend that wages and benefits sometimes don’t match those of comparable jobs in the same region. Amazon said its full-time workers receive “competitive hourly wages and a comprehensive benefits package” including healthcare insurance.

Overall, the jobs shift from retail stores to online distribution centers “is a plus because the jobs that are being lost in retail are, generally speaking, quite low-paid and usually not full-time,” said Michael Mandel, chief economist strategist at the Progressive Policy Institute. “The jobs being created in fulfillment centers are somewhat higher paid with more hours.”

Figuring out a strategy

For those losing jobs in retail, the key is figuring out where to shift or improve their skills to take advantage of the migration to online shopping or other retail sectors that remain on solid footing, said Lindsay Witcher, director of practice strategy at RiseSmart, which works with firms to help relocate their laid-off workers.

“The restaurant industry might be thriving and high-end malls are still growing; it’s about being smart about where the job market is growing,” she said. “You have to focus on identifying how your skills transfer to where the jobs are coming.”

“People have to take a step back, move away from the doom and gloom and see what is growing,” she said.

Twitter: @PeltzLATimes

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.