Black TV executives split on FCC’s proposed set-top box disruption

- Share via

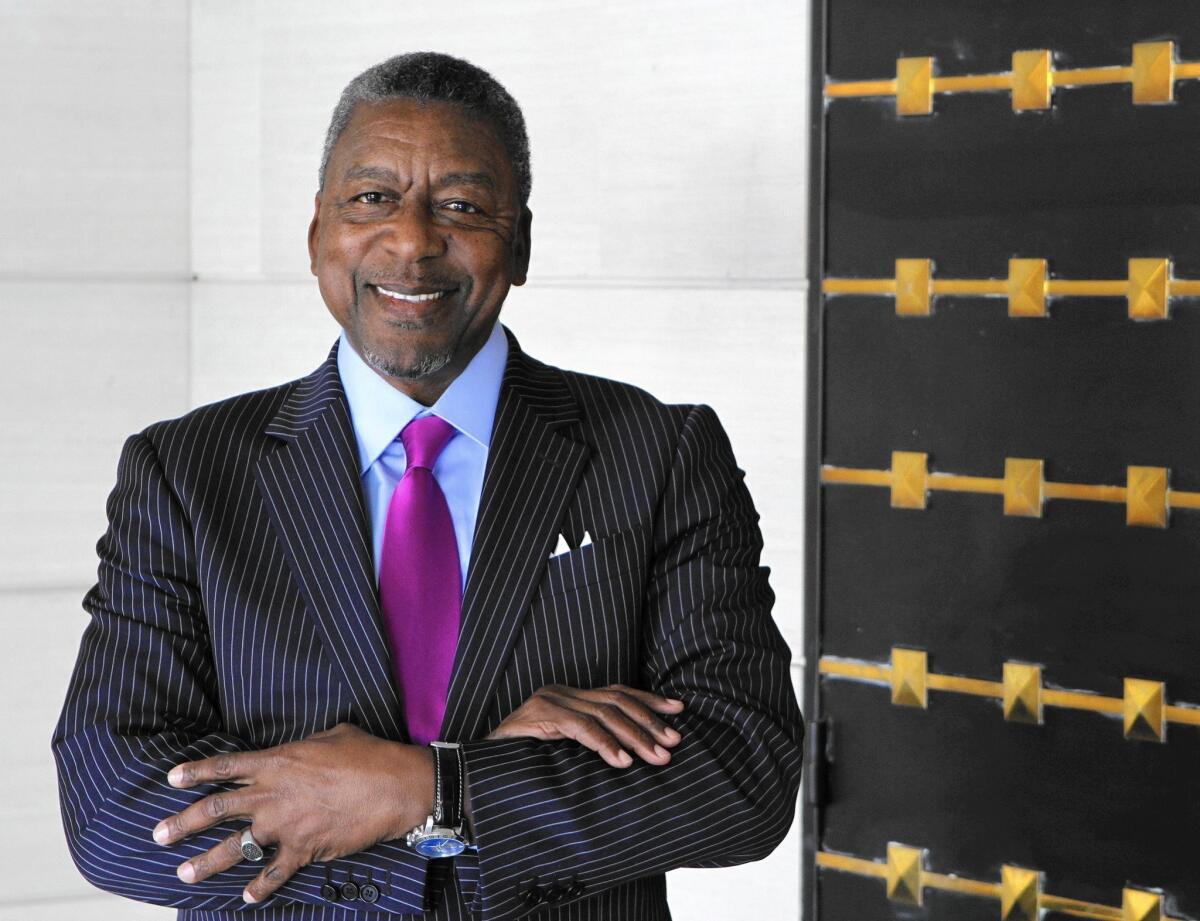

WASHINGTON — Robert Johnson and Alfred Liggins are good friends who share a unique bond: Each launched a successful cable TV network targeting African Americans, a rare achievement that makes them influential voices in the world of minority programming.

But as federal regulators consider new regulations for pay-TV set-top boxes that could dramatically reshape that world, the two black media titans have staked out polar opposite positions.

The fight between Johnson, the founder of BET, and Liggins, chairman of TV One, highlights the major role of black, Latino and other minority groups in a high-stakes debate playing out before the Federal Communications Commission that could rattle the cable and satellite industry. The sparring has intensified since the agency voted Feb. 18 to begin drafting rules to spur competition in the market for the decoding boxes that most pay-TV subscribers rent from their provider.

The proposal from FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler promises to rattle the industry. It would allow technology firms, such as Google, easier access to pay-TV programs that they could package into new multipurpose devices that Americans could buy to watch those shows along with streaming Internet shows.

The result, depending on who you talk to, could be a new model that allows more diverse content to reach Americans’ TV screens — or one that short-circuits hard-won gains by black, Latino and other minority programmers and leads to fewer quality shows.

“There’s no question this is a potential paradigm shift in how service is delivered in the industry, so there’s a lot of nervousness,” Rep. Tony Cardenas (D-Los Angeles) said. Last month, he joined with 24 other House members in writing to Wheeler raising concerns about the effects of the plan on minority-owned and independent content creators.

Wheeler’s plan pits pay-TV providers and major content producers, such as the top Hollywood studios, against high-tech firms and consumer groups. And in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, the minority programming issue is a key battleground in the broader debate over the future of the set-top box.

Johnson and Liggins, two of the most respected African Americans in the TV programming universe, are leading the charge from opposite sides — and taking some personal shots at each other in the process.

Wheeler’s plan would disrupt the relatively closed pay-TV ecosystem. Liggins benefits from that ecosystem because his network has a coveted slot in most cable and satellite programming packages.

For more than two decades, Johnson also was one of those insiders. But he sold BET to Viacom Inc. in 2003 and now chairs an online streaming company. As an outsider, he backs Wheeler’s plan.

“The universal set-top box pumps you straight to the big TV screen, where most African Americans, most Americans in general, want to watch their TV,” said Johnson, chairman of RLJ Entertainment. “The universal set-top box would open up tremendous opportunity for minority programming.”

But Liggins said the FCC plan risks the progress in recent years by cable and satellite companies in offering more diverse content.

Opening up the set-top box business to technology companies such as Google would threaten copyright and licensing payments that fuel program development, Liggins said. Those firms could mine viewer data and insert targeted ads in and around TV One shows and listings in program guides that would reduce the network’s revenue, Liggins warned.

“It costs millions and millions of dollars to create quality content,” said Liggins, whose network is home to the annual NAACP Image Awards show and the only daily newscast targeted at African Americans.

“If an advertiser can get our audience for a lot less money with a lot more data … then that devalues our business and devalues our content and puts us in a really precarious situation,” he said.

Minority organizations are taking positions, with most so far siding with the pay-TV industry. And lawmakers, such as members of the Congressional Black Caucus, have been lobbied for their backing.

Wheeler said his proposal would not alter licensing and copyright agreements with cable and satellite providers. And he promised that the final rules would prohibit third parties from placing ads in or around pay-TV shows when viewers watch them so that “the sanctity of the content” would be preserved.

“Nothing changes minority programmer relations with the cable company,” Wheeler said. “But it sure does create more opportunities for minority programmers to reach consumers over the Internet.”

But Wheeler’s vow was not included in the draft rules and he did not address the question of ads in program guides. The proposal says there was no evidence that the new devices would “replace or alter advertising, or improperly manipulate content,” although the FCC is asking for public comment on those points.

Both sides agree there needs to be more minority programming available to American viewers. The FCC has launched a formal inquiry into “the state of independent and diverse programming.”

“There are so few creators of content of color,” said Kim M. Keenan, president of the Multicultural Media, Telecom and Internet Council, which advocates for minority advances in communications.

But Keenan said the FCC proposal pits “the few successful minority programmers against each other.” And she and other opponents of the plan are skeptical that Silicon Valley high-tech companies, which have a poor record on diverse hiring, will produce devices that help elevate minority programming.

“Why choose a model that blows up the ecosystem with not even a promise that it will be better in the new ecosystem?” Keenan said. “We’re going to trade one gatekeeper for a diversity-worse gatekeeper.”

Victor Cerda, senior vice president of corporate strategy at Vme TV, a Spanish-language network on pay TV and PBS, said the number of Latino-focused channels slowly is increasing. Vme TV, which has been on pay TV for about five years, is the third-most-viewed Latino-focused network, behind Univision and Telemundo. Four years ago, Cerda’s company launched Vme Kids, airing Spanish-language children programming.

“Improving the offerings of minority, independent programmers in the world of TV in the U.S. is evolving and there’s still a ways to go,” said Cerda, who opposes the FCC’s plan.

“There’s a serious risk of undercutting the advancements we have made with the cable and satellite companies to get carriage and get content that is good content.”

Liggins said streaming services are hoping to use the new devices as shortcuts to reaching a broader audience. Pairing online offerings, such as Johnson’s Urban Movie Channel, next to TV One in new program guides would allow universal set-top-box makers to sell advertising in those guides to companies looking to reach Liggins’ viewers.

“Johnson has to do it like Netflix: Acquire content that people want and that they’re willing to pay for,” Liggins said. “He’d rather be paired up next to TV One and try to draft off of my audience and let me spend all the money.”

Liggins and Johnson each criticize the other as more concerned with narrow self-interests than the greater good.

“Alfred goes around saying, ‘Protect me and keep out all of those other minority programmers who would have a shot in the universal set-top-box world,’” Johnson said.

But he said minority pay-TV subscribers are targeted by only a handful of networks, out of the hundreds they pay for with subscription fees as well as set-top-box rentals. About 99% of the nation’s 100 million pay-TV subscribers rent at least one set-top box, with the average household paying $231 a year in fees, according to the FCC. Supporters of Wheeler’s proposal said competition would reduce the costs of those devices.

“The argument that by keeping minority Americans, who have one of the lowest median incomes in the country, paying $231 [a year] so they can get four cable programming channels doesn’t make any sense,” Johnson said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.