Outdoor retailer Patagonia puts environment ahead of sales growth

- Share via

High-end outdoor clothier and gear maker Patagonia Inc. is out to prove that a company can generate strong sales while being nearly fanatical about environmental concerns.

The Ventura company was the first major clothier to make fleece jackets out of recycled bottles. Nearly a third of the power for its headquarters and adjoining child-care center comes from solar. And it donates 1% of its sales to environmental causes.

With Patagonia being a privately held company, its finances are not public, but it says it’s riding a growth curve. It opened 14 new stores last year, bringing to 88 its wholly owned retail outlets throughout the world. Executives said the company had $540 million in sales in the 12 months that ended in April, an increase of more than 30% over the same period a year earlier.

Furthermore, they said, Patagonia has doubled revenue and tripled profit since 2008.

But is it fair to say that the environmental dedication of the company is a key to its claimed success?

Patagonia executives say yes.

Chief Executive Casey Sheahan said customers were willing to pay $25 for a T-shirt, $20 for wool socks and $180 for a light jacket because they knew Patagonia inflicted less damage on the environment than other clothing makers did.

And, he said, other companies are catching on.

“I think a lot of big companies are doing things like this because it’s a better way of doing business,” he said as he strolled company headquarters where clothing designers shuffle around in flip-flops while other workers shape surfboards that they test off a nearby beach.

Patagonia co-founded the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, a group of retailers and clothiers, including Target, Wal-Mart and Levi Strauss, that is committed to slashing the environmental impact of their operations.

But analysts said Patagonia’s eco-friendly philosophy was probably only one factor in the company’s ability to grow.

More important, said Richard Jaffe, a retail and apparel analyst with investment firm Stifel, Nicolaus & Co., is that Patagonia has a reputation for making products a cut above much of the competition.

“They are doing things incrementally better,” Jaffe said.

Patagonia may also be benefiting from an overall increase in sales in outdoor goods across the country. During the recession, industry experts say, many Americans turned to outdoor recreation as a cheaper alternative to diversions such as foreign travel.

Outdoor product sales in the U.S. totaled $25.3 billion in 2011, representing an increase of nearly 11% compared with 2010, according to the Outdoor Industry Assn., a trade group for outdoor retailers. In the same period, overall retail sales grew only about 5%, according to the National Retail Federation.

“Sales numbers were insane over the past few years,” said Avery Stonich, a spokeswoman for the Outdoor Industry Assn. “The ‘stay-cations’ had a big impact on those sales numbers.”

Patagonia also benefited from some moves it made.

The company previously concentrated on rugged clothing and gear for endeavors such as hiking and rock climbing. But about eight years ago it introduced a line of surf-inspired clothing and beach products, including surfboards, that have proved popular.

Patagonia also cut overhead by consolidating some global factories and putting more focus on Internet sales.

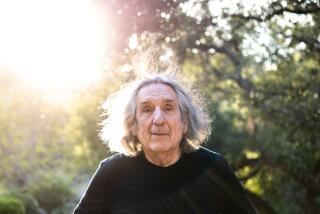

But even Patagonia’s founder and sole owner, Yvon Chouinard, 73, said the company was not likely to keep up its current growth pace.

Chouinard, who began forging his own climbing gear in the 1950s and turned that into an outdoor clothing business, called Patagonia’s recent jump in revenue an aberration, fueled partly by the recession.

Even though Patagonia is hardly a discount line, he said he believed consumers spent more in tough times on quality outdoor equipment and clothing that last longer. Also, Patagonia promises to repair or replace clothes that don’t meet customer satisfaction.

Chouinard predicted sales would grow steadily but at a more modest rate, about 15% annually, with only two or three new store openings per year.

He’ll continue to press for more emphasis on Internet sales because, he said, buying and retrofitting each brick-and-mortar store can cost as much as $2 million. “The return on investment on retail is much lower than on Internet sales,” he said.

But no matter how the business fares in the future, Chouinard wants the commitment to the environment to continue. In fact, he took a step to try to ensure that it does, even beyond his demise.

On Jan. 3, the first day of business this year, Chouinard marched into the office of the secretary of state in Sacramento to be the first head of a company in California to file “benefit corporation” papers.

Traditionally, for-profit companies are required to serve the interests of shareholders above all. But a law passed by the state Legislature last year created the category of “benefit corporation” to allow such companies to adopt policies that “create a material positive impact on society and the environment.” The law took effect this year.

It was designed to protect a company from shareholder lawsuits saying that environmental efforts dilute the value of stock.

Chouinard said he made the move so that if Patagonia became a public company after he and his wife passed on, it would continue to donate to environmental causes without fear of being sued by shareholders.

“Now I can say what our values are, and that forever the company must continue to donate 1% of sales,” he said.

His prediction of slowing sales growth for Patagonia was of less concern.

“It makes no difference to me,” Chouinard said, “as long as we stay out of debt.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.