5 years after financial crash, many losers — and some big winners

- Share via

Never let a crisis go to waste, says an old rule of politics.

For some major players in the economy, the financial crisis that began five years ago this month with Lehman Bros.’ collapse turned out to be as much an opportunity as a calamity.

Although the memories that the anniversary evoke are overwhelmingly grim — cascading home foreclosures, bank failures, massive layoffs, diving stock prices — five years later some spectacular winners have emerged from the maelstrom, along with a more familiar list of pitiable losers.

PHOTOS: Key players in the financial crisis

Not surprisingly, many of those who reaped gains from the disaster were able to make use of the incredibly cheap money flowing from the Federal Reserve.

That also means the final chapter of the 2008 meltdown has yet to be written: As the Fed debates cutting back on its trillions of dollars of support for the financial system, it could threaten the health of some of the biggest beneficiaries of that largess.

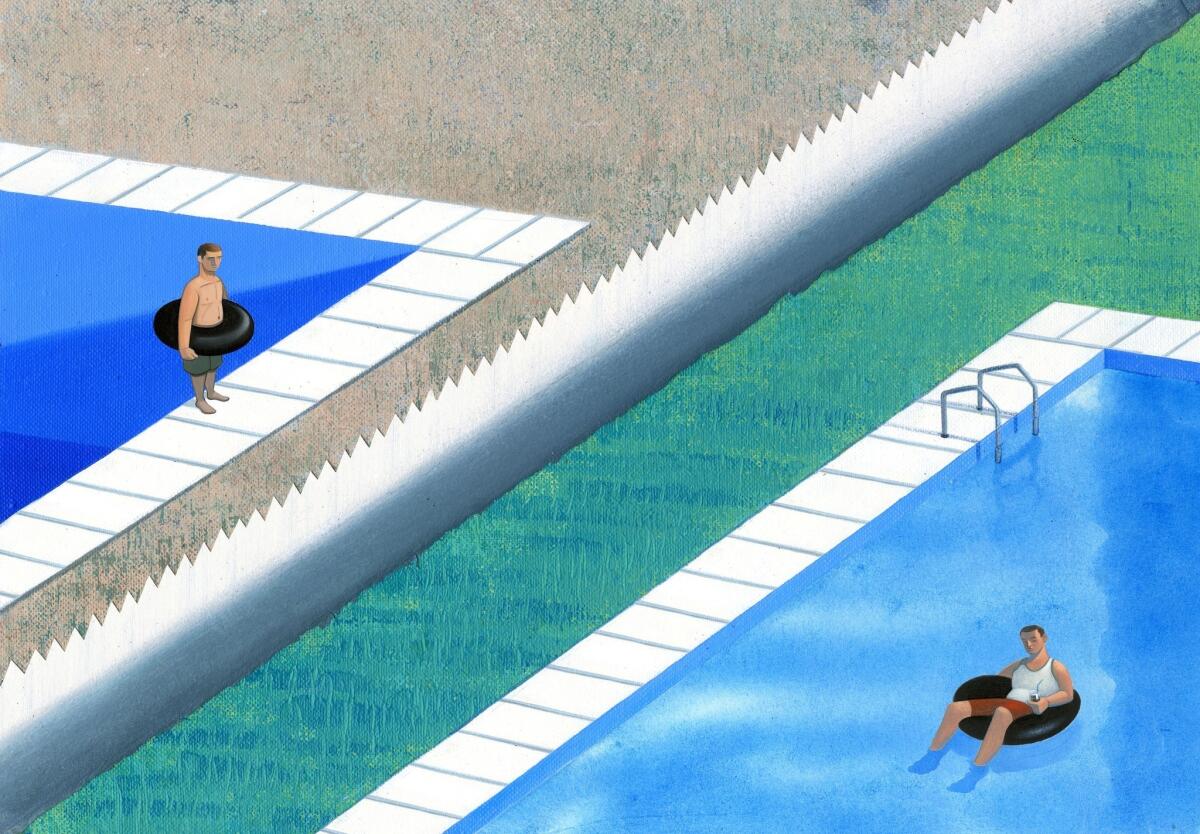

Still, the gulf between the post-crisis haves and have-nots isn’t likely to narrow significantly soon.

Here’s a look at four major winners and four major losers from the 2008 catastrophe and its aftermath:

WINNER: The banks. In the second quarter of this year U.S. banks earned a total of $42.2 billion — the biggest industry profit in history, and double the earnings of the same period in 2010.

It’s no accident that the banks have prospered mightily since the crash, said Neil Barofsky, who was the watchdog over the U.S. bank bailout program launched in September 2008.

“We turned the entire resources of the nation toward one goal: setting up a situation where the banks could earn their way out of this,” said Barofsky, now an attorney at Jenner & Block in New York. The plan was not, he lamented, “about holding institutions accountable” for the debacle.

After brokerage giant Lehman failed Sept. 15, 2008, credit seized up and the financial system became a place of titanic falling dominoes: Merrill Lynch & Co., Wachovia Corp., American International Group Inc., Washington Mutual Inc. Rotten home loans were at the core of it all.

The Bush administration scrambled for a plan to restore confidence in the system. The $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, was created to buy bad loans from banks. But the government quickly switched course and instead used the money to make investments in hundreds of banks, bolstering their capital cushions.

Yet in the longer run, TARP was less significant for many banks than the aid of the Federal Reserve under Chairman Ben S. Bernanke.

By hacking short-term interest rates to near zero and holding them there since the end of 2008, the Fed has slashed bankers’ cost of money — particularly deposits — to well below what they earn on loans and investments. Hence, record profits.

Meanwhile, “too big to fail” remains a huge risk to the financial system. The five biggest U.S. banks, led by JPMorgan Chase & Co., controlled 38.4% of total bank assets in 2007. Now they control 43.9%, according to research firm SNL Securities.

“‘Too big to fail’ has become ‘too ginormous to fail,’” said Barry Ritholtz, who wrote “Bailout Nation” in 2009.

LOSER: Savers. The Fed’s decision to keep short-term interest rates near rock bottom for nearly five years has devastated the income of tens of millions of Americans.

In the mid-2000s, savers in banks were routinely earning 4% or more on one-year bank certificates of deposit, or $2,000 in annual interest on a $50,000 nest egg.

The average rate now: 0.23%, according to Bankrate.com. The same $50,000 nest egg earns just $115 a year in interest at that rate. “And after inflation they’re actually losing ground,” said Andrew Lo, a finance professor at MIT in Cambridge, Mass.

The Fed has argued that the wounded economy’s need for cheap credit superseded savers’ need for income. Bernanke also has been blunt about encouraging savers to hunt for higher returns by shifting cash to bonds or other assets.

But many Americans have refused to budge. The result: $7 trillion sits in bank passbook and money-market accounts earning close to nothing. That sum was $4 trillion five years ago.

James Bianco, head of Bianco Research in Chicago, thinks that the cash hoard points up another casualty of the crash: the willingness to take risks.

“People think too much of this stuff is manipulated,” Bianco said of markets since 2008. “Their conclusion is ‘It’s not a fair game.’”

WINNER: Corporate America. Record bank profits are a slice of a much bigger pie — a stunning profit boom at major U.S. corporations.

The government’s broadest measure of corporate earnings reached an annualized rate of $2.1 trillion in the second quarter, an all-time high and more than double the rate at the end of 2008.

The dramatic rebound in earnings has occurred despite a slow-growing U.S. economy and continued weakness abroad, particularly in Europe.

Corporations’ profit success stems in part from the layoffs and other deep cost-cutting many firms undertook in the 2008-09 recession — and their relative lack of domestic hiring since. And, like the banks, companies have reaped the benefits of the Fed’s super-low interest rates by refinancing debt.

The surge in earnings has helped buttress stock prices, which are near record highs. That has lifted the retirement accounts of millions of Americans who own shares, notes Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Sen. John McCain’s economic advisor in 2008 and now head of the free-market-oriented American Action Forum in Washington.

In that sense, the profit boom “doesn’t go exclusively to the rich,” Holtz-Eakin said. “It also goes to union pension funds, for example.”

Still, corporations’ enhanced financial power now is coupled with the greater political power they gained from the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling in 2010, which vastly expanded their ability to lobby politicians.

For big business, “it’s a golden age for sure,” said economist Ed Yardeni, head of Yardeni Research in New York.

LOSER: Low-skilled workers. Five years after the crash, perhaps the greatest disappointment worldwide has been the lack of job creation.

In the U.S. the official unemployment rate has fallen from a high of 10% in 2009 to 7.3%. But the decline has come in part because many dejected jobless have simply dropped out of the labor force. A broader unemployment rate, including so-called discouraged workers, stands at a painful 13.7%.

What the 2008 crash exposed is the deepening predicament faced by low-skilled and unskilled workers everywhere: A slow-growing world economy means many companies can’t justify hiring. At the same time, automation continues to replace human labor.

“The globe is awash in humans willing to do mundane, low-skilled types of work,” said Edward Leamer, a UCLA economics professor. “That share of labor is going to continue to be left out” of any economic recovery.

Even for the employed, the labor glut gives companies more leverage to hold down wages and benefits for workers who don’t command skills that are in demand.

Some workers are fighting back: Fast-food employees staged strikes in dozens of U.S. cities last month, demanding a boost in the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour from $7.25.

The California Legislature last week voted to boost the state’s minimum wage from $8 an hour to $10 by 2016.

But in the long run, the surest path to higher wages is learning new skills that match what businesses need most, MIT’s Lo said.

“We need to retrain our labor force,” he said. “But that takes time.”

WINNER: The super-rich. It takes money to make money. And many of the extraordinarily well-off who managed to keep their wealth after the 2008 crash have seen their fortunes balloon once again.

The Fed’s low interest rates have driven up two favorite assets of the super-rich: real estate and stocks.

A new report by research firm Wealth-X pegs the number of “ultra-high net worth” individuals — those with at least $30 million in net worth — at a record high of nearly 200,000 worldwide this year, up from 186,000 in 2011.

Their total wealth has surged to $27.8 trillion from $25 trillion two years ago, Wealth-X estimated.

To put the numbers in perspective, those 200,000 people control wealth equivalent to the combined gross domestic products of the U.S., Japan, Brazil and India.

The riches at the very top have helped widen the income-inequality gap here and abroad.

A new study by Emmanuel Saez, an economics professor at UC Berkeley, found that the top 10% of U.S. earners captured 50.4% of total income in 2012, a level higher than any other year since 1917.

“We need to decide as a society whether this increase in income inequality is efficient and acceptable and, if not, what mix of institutional and tax reforms should be developed to counter it,” Saez said.

But with Washington deadlocked on nearly everything, that debate still seems DOA.

LOSER: Foreclosed and underwater homeowners. The foreclosed homeowner will always be the face of the 2008 crisis.

The bursting of the housing bubble has cost 4.5 million families their homes via foreclosure over the last five years, according to data firm CoreLogic Inc. In many hard-hit communities the total cost has been incalculable: lives disrupted, neighborhoods degraded, tax revenue slashed, credit ruined.

What’s more, millions of Americans remain trapped in homes whose value is below the mortgage balance. The number of homes with negative equity totaled 7.1 million at the end of June, or 14.5% of all homes with mortgages, CoreLogic estimates.

Yet the losers’ ranks here are thinning as home prices rebound. The S&P;/Case-Shiller index of home prices in 20 major cities has risen 19% since March 2012 after diving 35% from its 2006 peak.

The number of homes in some stage of foreclosure plunged to 949,000 in July, down one-third from a year earlier, CoreLogic said. And the negative-equity mortgage share has shrunk by about half since the end of 2009, when it hit 26%.

With mortgage rates rising, however, the fear is that home prices could resume their slide and reignite the crisis. But Sam Khater, deputy chief economist at CoreLogic, said the housing market is more likely to just lose momentum.

“We see a slowdown in the rate of price appreciation, but not a decline,” Khater said. With new construction depressed, foreclosures falling and the number of homes for sale relatively limited, supply won’t soon overwhelm demand even if buying interest weakens, he said.

Still, TARP watchdog Barofsky said his biggest regret was that he couldn’t divert more money away from aiding the banks and toward stemming the wave of foreclosures. The political will wasn’t there, he said.

“We had our foot on the throat of these institutions, but we just weren’t able to get the necessary traction to get help for homeowners,” Barofsky said. “It slipped away.”

WINNER: The index-investing concept. For decades, many experts have preached the wisdom of investing in low-cost “index” funds that simply replicate average market performance, rather than trying to beat the market via high-fee “active” management.

It took the 2008 market crash to bring that message home for many Americans.

Vanguard Group, the dominant index-fund company, has been the standout winner of fund companies since the crash. The firm’s total stock and bond fund assets have rocketed to $2 trillion from $1.1 trillion at the end of 2007.

In the first eight months of this year the company took in $51 billion in net new cash to its conventional stock and bond funds, according to Morningstar Inc. That trounced the competition: The next-biggest gainer was JPMorgan Chase, with $15.6 billion in net inflows.

Vanguard also has been a leader in offering exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, which are designed to replicate broad or narrow market indexes, with minimal management fees. ETF industry assets have soared since 2007 to $1.5 trillion.

Investors’ rush toward index funds stems from “the perceived failure of active management,” said John Rekenthaler, vice president of research at Morningstar in Chicago. Rightly or wrongly, investors may have expected their actively managed funds to protect them from the 2008-09 market collapse, he said.

“They’re now saying, ‘I’m not going down that road again,’” Rekenthaler said.

Shifting to index investing essentially is deciding that if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em: Just own the entire market, and for a lot cheaper than a stock-picking fund manager would charge you.

LOSER: Stock exchanges. For the last 10 years or more the media have written reams about the end of the traditional stock broker.

And going with them, now, are the stock exchanges.

U.S. stock trading volume has shrunk dramatically since 2008, in part as many small investors have abandoned equities. That has accelerated the pace of mergers in the trading business, as exchanges partner up with stronger players or consolidate to grab more share of a disappearing market.

NYSE Euronext, parent of the once-iconic New York Stock Exchange, is selling out to commodities trader IntercontinentalExchange. And two large electronic stock trading networks, Bats Global Markets and Direct Edge Holdings, announced merger plans last month.

As trading systems have become ever faster and more complicated, they’ve also been victimized by their own technology. Some high-profile snafus in recent years — including the “flash crash” in 2010 and Nasdaq’s sudden shutdown last month — have further soured average investors on stocks.

Bianco of Bianco Research believes the exchanges made a crucial mistake years ago by courting high-frequency traders, or HFTs, which many individual investors see as villains in the market. Now, even high-speed trading volume is declining.

“The exchanges look at it and say, ‘If we get rid of the HFT guys, we got nobody,’” Bianco said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.