- Share via

There’s no shortage of demand for beef.

Prices are up. Grocery stores are limiting how much each customer can buy. Last week more than 1,000 Wendy’s restaurants ran out of hamburgers.

There’s also no shortage of cattle earmarked to be turned into beef.

But prices for those animals have dropped. Sales are down. At a recent livestock auction in the San Joaquin Valley, just a handful of buyers bothered to make an appearance.

The problem is in the middle of this pipeline: the crisis at meat processing plants.

Employees at these factories work closely together, and thousands nationwide have become infected with the novel coronavirus. At least 20 have died. As their workers fall ill, the plants have lowered capacity or temporarily shut down.

The plants’ diminished capacity means some beef can’t get processed, and that has thrown cold water on the market for cattle: Why pay top dollar for the animals if you might not be able to sell them later?

That’s a problem for California, the nation’s fifth-largest cattle-producing state. In a good year, commercial ranchers could aim to get more than $1 per pound for a premium calf. Now, the expected price has dived 15% to 25%, said Mark Lacey, president of the trade group California Cattlemen’s Assn.

“We’ve had some major droughts, we have had some bad market years, but this is unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” said Megan Brown, a sixth-generation cattle rancher and manager of Brown Ranch in Plumas and Butte counties. “Even in the family history, nothing compares to this.”

The journey a hamburger takes from ranch to plate is long and winding.

During the coronavirus crisis, food producers, distributors and retailers in California, producer of much of the U.S. food supply, scramble to adapt.

Calf-producing ranchers, such as Brown and her family, are at the beginning of the chain. Calves are typically kept with their mothers until they weigh 500 to 600 pounds. Then they are sold to a stocker — a rancher who will continue to grow the cattle by feeding them grass until they reach about 900 pounds.

Then the cattle go to a feedlot to be fattened up before being sold for slaughter, butchered at a meat processing plant and sold to wholesalers, supermarkets and restaurant chains.

The entire process — from farm to fork — can be likened to an hourglass shape, said Dave Daley, administrator for the Paul L. Byrne Memorial University Farm at Cal State Chico. Processing plants are always the narrowest point; if one shuts down — particularly a large one — it can back up the entire system.

The bottleneck at the plants has always been tight, “but now it is really tight because of COVID-19,” he said. “We have the supply of cattle at the upper end. We’ve got to get it through the narrow constriction.”

The feedlots have been particularly slammed by the bottleneck. With slowdowns at the processing plants, feed yard operators are forced to keep the cattle longer. That means more feed and maintenance expenses.

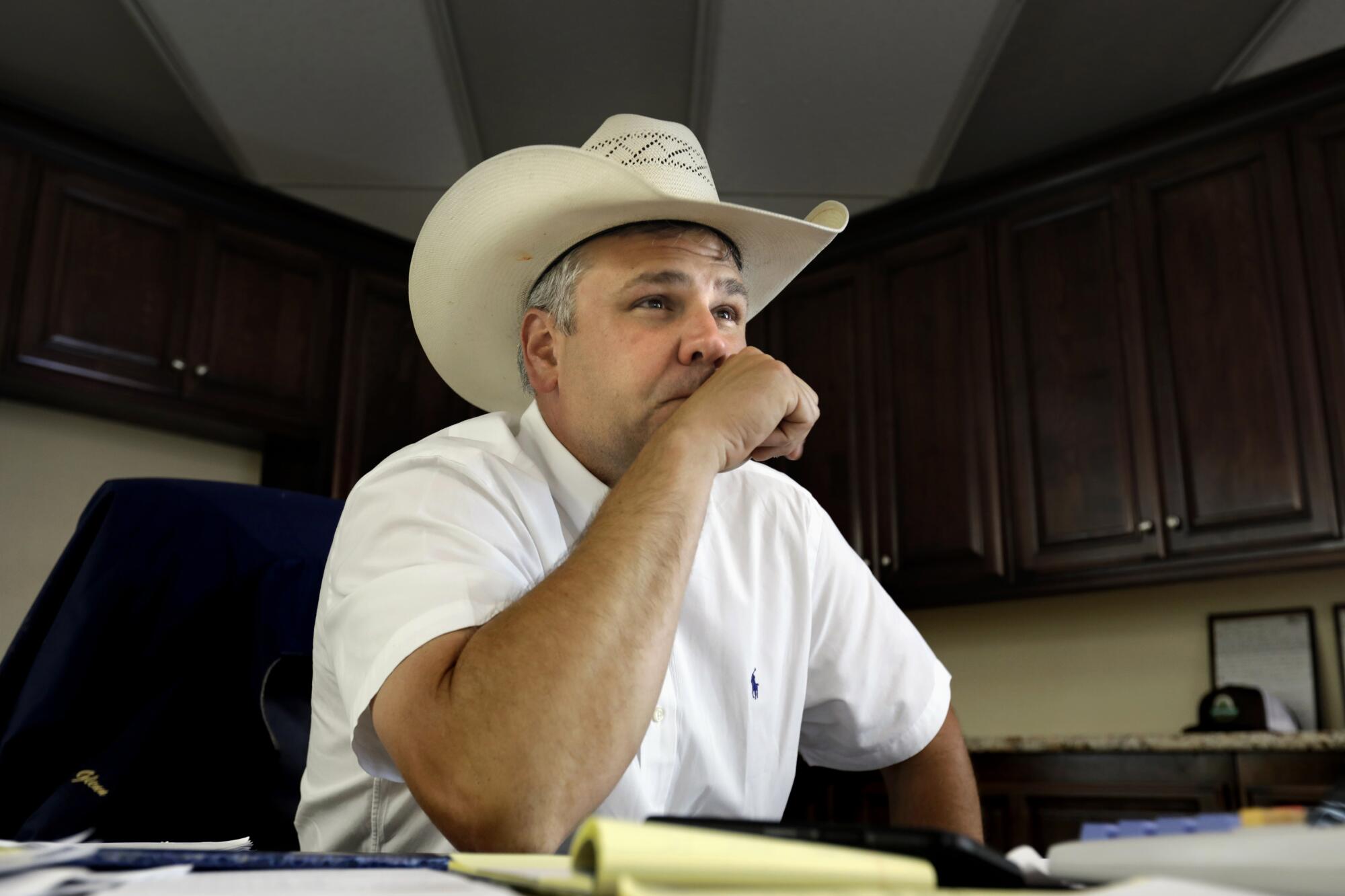

A few months ago, cattle prices were $1.19 per pound for livestock slated for May and June delivery to meat processing plants. The price has since dropped to 92 cents per pound, said Jesse Larios, who operates two feed yards in Imperial County.

Larios said his cows are now worth less than what he paid for them. Not taking into account what he has spent on feed and other expenses, he said he’s looking at a loss of $365 per cow — and he has thousands of them.

Larios said he’s not planning to buy any livestock in the next month. There’s just too much uncertainty in the market, especially because feeders typically buy cattle with an eye toward selling them to slaughter six months to a year later.

“We are trying to learn and understand where this virus will be in that time frame,” said Larios, who — following in the footsteps of his father and three uncles — has worked in feed yards for 22 years. “Will the restaurants reopen in six to 12 months? Will they serve the same amount of customers, or will they have social distancing? We cannot purchase animals at the same capacity if we aren’t sure what the production rate will be.”

As feed yard operators halted purchases, commercial ranchers saw cattle prices fall. That forced difficult choices: Keep cattle longer in hopes of a better market, racking up additional costs to feed the animals while waiting? Or sell immediately at a loss?

Lacey, the trade group president, didn’t have much of an option. Dry weather early this year at his family’s Lacey Livestock in Mono and Inyo counties meant less vegetation than usual grew in the pastures where his cattle graze.

During the drought in 2014, Lacey recalled, cattle prices were much higher, so ranchers could afford to rent pasture land in other states and move their cattle there.

“This time, that’s not the case,” said Lacey, who serves as manager of his family’s business. “The prices just aren’t there.” He managed to move some of his cattle to the Midwest and sold others, taking bigger losses than he expected.

Cattle are typically sold in a few ways: in a private treaty between seller and buyer or at auction.

On a recent Thursday at the Overland Stock Yard in the Kings County city of Hanford, the electric doors of a pen opened, and four calves scrambled onto a large floor scale, penned off from the rest of the room. They were ushered around by a man with a long pole that was tipped with a red, clicking paddle.

As the cattle moved in formation around the pen, Dustin Burkhart, Overland Stock Yard’s auctioneer and co-manager, started the bidding. Roughly 30 people sat in the indoor amphitheater — socially distanced — ready to make their bids. Scores of others watched online.

Eventually, 21,000 head of cattle were sold on the auction’s online platform.

“Those are great numbers,” said Jason Glenn, co-manager of the auction house, but there was a caveat: Those cattle won’t be ready for slaughter until 2021.

For cattle that were closer to slaughter, it was a different story. The auction house emptied out, with only seven buyers remaining. Only 85 head of slaughter-ready cattle were shown, compared with the usual 300 to 400.

Prices fluctuated between 46 cents and 55 cents per pound.

“We’ve never seen anything like this,” Glenn said. “Not after 9/11. Not after the last financial downturn. Not ever.”

During the same week last year, the auction house processed roughly 670,000 cattle, he said. This year, the weekly number was down to 425,000.

Even before the coronavirus outbreak hit, prices were distressed because there was a lot of cattle on the market. The pandemic created more volatility, said Kate Miller, owner of IMB Cattle Co. in Arkansas, who has been in beef marketing for 10 years.

Other meat producers are also having a difficult time.

As coronavirus-related restaurant shutdowns slashed demand for pork products, and as slaughterhouses closed temporarily to slow the spread of COVID-19 among workers, some U.S. hog farmers — faced with a declining market and no room to hold additional hogs — have resorted to killing piglets.

It’s possible to slow the growth of cattle by pulling them off grain diets and putting them on a maintenance plan, Miller said, but that doesn’t work with pigs. And once a hog reaches about 325 pounds, it is too large to be processed at a plant.

Pigs also tend to be slaughtered at a much younger age than cattle, meaning hog farmers have less time to manage the ongoing crisis. Pigs can be ready for slaughter by six months of age, when they weigh about 280 pounds, according to the National Pork Board marketing program. By contrast, most cattle are between 18 and 24 months old, said Wade Lacque, co-owner and manager of Orland Livestock Commission Yard in the Sacramento Valley.

Ranchers and feeders balked at the idea of killing cattle, noting that it would be a major financial loss since the animals are so expensive to raise.

As an alternative to selling at a loss at auction, Brown, the sixth-generation farmer, decided to try getting some of her animals slaughtered and selling the beef directly to people who want to eat it.

Recently, she advertised a “hamburger share” on social media for friends, family and nearby residents. Customers pay her directly via PayPal, and she delivers pounds of ground meat to their porches.

She gets the beef slaughtered and processed at a small U.S. Department of Agriculture facility that doesn’t handle the volume of meat that larger plants do.

The profit margins are “a drop in the bucket” compared to what her family usually makes at auction, and it takes a lot of time and work to deliver the cows for processing, she said. But it’s better than nothing at all, and she said she hopes it’ll lead to continued sales in the future. After all, the farm-to-table movement has grown in strength lately.

In the past, she’d done a few beef shares but had only ever slaughtered a handful of older calves that weren’t fit to go to auction, like the smallest or one with a bad eye. This is the first year she’s had access to the cream of the crop.

“I don’t always make a lot of money, but it’s goodwill for the community,” Brown said.

Like many other California cattle ranchers, Brown’s family has been in the business for a long time, about 100 years. Their two ranches cover 4,000 acres.

“It’s a lifestyle thing,” said Lacque of the Orland Livestock Commission Yard. “People enjoy ranching ... being out in the open, in the hills. Riding their horses and being with the cattle.”

The third-generation auction-yard manager said he can’t count the number of phone calls he has received in the last month from ranchers seeking advice about what to do. He says he doesn’t have any solid guidance because no one has been in this situation before, and it’s unclear what the future will bring.

Business has been tough for him, too. The auction yard makes its money from commissions on sales, and for the last month it has sold only about 30% to 40% of its normal volume of cattle.

“It’s going to be a hard year,” he said. As for his customers, “hopefully most of them will make it through and still be ranching next year. I’m sure some of them won’t be.”

Rust reported from Hanford, Calif., and Masunaga and Parvini from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.