Carmakers promised to cut emissions. Environmentalists haven’t forgotten what happened next

- Share via

The chief executives of the world’s biggest automakers gathered with President Obama at the Washington Convention Center in 2011 to announce they had agreed to double the average fuel economy of their vehicles to 54.5 miles per gallon — the largest increase in history.

Five years later, after Donald Trump was elected, the companies asked the president-elect to roll back the standards. He did.

That history was fresh in the mind of climate activists and others as President Biden on Thursday signed an executive order on the White House lawn, also flanked by Detroit auto executives, that set an ambitious though voluntary national goal of having half of all vehicles sold in the U.S. be emissions-free by the end of the decade.

“Trusting auto companies to comply with a voluntary pledge is like believing your New Year’s weight loss resolution is a binding contract,” said Dan Becker, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s Safe Climate Transport Campaign. “They violated their commitment by going to Trump.”

Keeping the lights on is getting harder as the American West grows hotter, drier and more flammable.

But this time the automakers point to investments and pronouncements they made about moving toward carbon neutrality even before Biden signed his executive order Thursday as evidence of their sincerity.

“Collectively, the auto industry has committed to investing more than $330 billion to bring exciting new electric vehicles to market, including plug-in hybrid, battery and fuel cell EVs,” John Bozzella, president and CEO of the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which lobbies for major automakers, said in a statement.

General Motors Co., for instance, said in June that it will spend $35 billion on more than 30 plug-in vehicles and a total of four battery plants by 2025. And Ford Motor Co. announced a month earlier that it would boost its bet on plug-in models by more than a third, to $30 billion, with the goal of having electric vehicles making up 40% of its sales by 2030.

Stellantis, formed by the merger of Fiat Chrysler and PSA Group, said last month that it has budgeted more than $35 billion for electrification and software. It will have five battery factories in Europe and North America by the end of the decade.

Biden’s announcement, coupled with new emission regulations also unveiled Thursday, will be key to achieving his ambitious climate goals of slashing U.S. emissions by 50% by 2030 and achieving a carbon-free economy by 2050. Neither target can be met without changes to the transportation sector, the largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

“The future of the American auto industry is electric,” Biden said Thursday with an array of electric and hybrid vehicles on the White House’s South Lawn as a backdrop. “It is electric; there’s no turning back.”

Mandatory regulations

The White House says it has confidence in the pledge because it will be coupled with the mandatory fuel economy regulations as well as public investments in infrastructure such as charging stations.

“Representatives from the automakers were literally at the White House standing with the president, shoulder to shoulder, when announcing this goal,” the White House said in a statement.

Reaching the goal in the next nine years will require a big change in consumer acceptance and the automakers say they will need government help.

Bozzella said the federal government is going to have to follow through on commitments made by the Biden administration to drastically ramp up the number of charging stations available on U.S. roads and expand the number of tax incentives for consumers to consider electric models.

“The U.S. needs to rapidly expand its charging and hydrogen fueling infrastructure, retool existing manufacturing facilities and build new ones, prepare and position our workforce to lead this transition, and provide consumer incentives to make these vehicles affordable and accessible to a wide range of customers,” Bozzella said.

Biden’s goal was paired with an announcement that his administration was crafting mandatory fuel economy and tailpipe emission standards.

First step

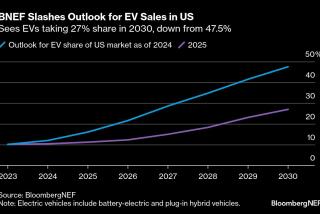

“The standards are a solid first step, but increasing EV adoption from 2020’s 2% to 50% is a daunting task, requiring more aggressive standards for model years 2027 onwards and a suite of EV policies like enhanced purchase incentives that require approval by Congress,” BloombergNEF analyst Corey Cantor wrote in a note.

Under the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposal, automakers would be required to pare their fleetwide emissions by 10% for model year 2023 cars and then a 5% greater emission reduction improvement for each model year after that through 2026.

But actual real-world emission reductions could be diminished under flexibilities cherished by automakers, including the double counting of electric vehicle sales and extra credit for technologies that make cars more fuel efficient but don’t necessarily show up in tailpipe readings.

“The key question here is: Is the auto industry going to live up to its promise,” said Simon Mui, deputy director of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s clean vehicles and fuels group. “You need to have that goal in place, but you need to solidify it.”

In all, the cumulative emission reductions that automakers have to achieve is 30% lower than the standards Obama proposed, in part because of the credits, Mui said.

“EPA going forward needs to fix that issue,” Mui said.

In a statement, the agency cautioned against making “an apples to oranges comparison” and said the additional flexibilities provided in the rule were temporary to support the transition to zero-emission vehicles.

“The Obama standards had greater cumulative [greenhouse gas] emissions reductions because the emissions reductions started earlier,” the EPA said. “By 2026, EPA’s proposed standards are more robust than where the Obama standards left off in 2025 and would be the most robust light-duty vehicle GHG standards ever established.”

Carmaker bankruptcies

Major automakers, including GM and Chrysler, went bankrupt during the Great Recession and survived after receiving government bailouts. That led to a series of agreements with the Obama administration on fuel efficiency standards, leading to the 2011 pledge to read an average of 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025.

But shortly after Trump was elected the industry through its trade association asked the EPA to withdraw a decision made in the Obama administration’s final days that upheld light-vehicle greenhouse gas emission standards through 2025, arguing a review of the rules had been unfairly cut short.

Several of the automakers even backed the Trump administration in a legal battle that could have neutered California’s longstanding authority to set its own more stringent carbon-emission rules.

Trump, in March 2020, finalized a plan which would have set a target of average fleetwide fuel economy of roughly 40 mpg for 2026 model-year cars, trucks and sport-utility vehicles.

California regulators brokered a compromise with five automakers in 2019 to boost the average fuel economy of their fleets toward an average of almost 50 mpg by 2026.

The proposals Biden announced Thursday would mandate fleetwide vehicle fuel economy of 52 mpg by 2026, up from 40 this year.

Environmentalists say in the years since Obama’s fuel economy rules were issued the pace of climate change has accelerated, adding to the urgency to enact stricter standards.

“I think we are in a different time period,” said the NRDC’s Mui. “Climate change was for many a vague concept, but it’s become personal with individuals being impacted from droughts to wildfires. Everyone is starting to see the impacts versus maybe a decade ago and the time to act is now and to rapidly deploy the technologies we have and do that quickly.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.