Trump’s trade deal with China turned out to be a huge, costly bust

- Share via

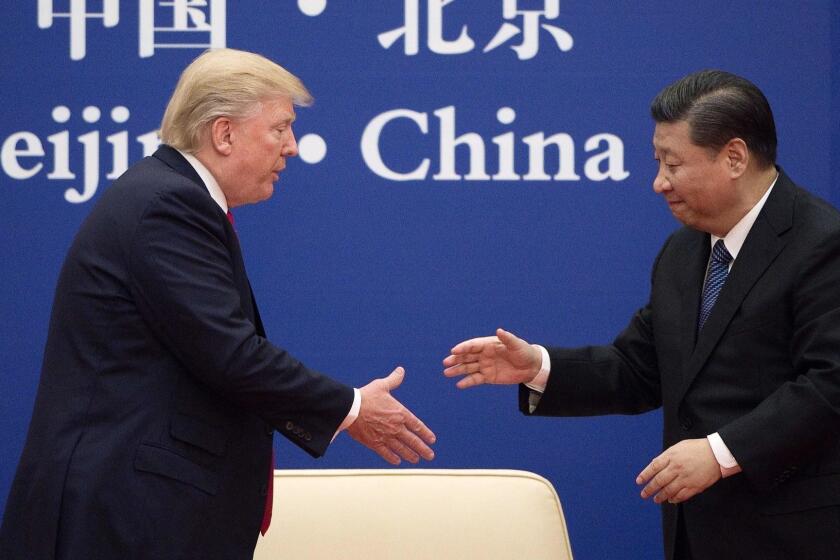

The final tally is in, and the numbers are grim: Donald Trump’s huge trade deal with China — the deal he trumpeted as a “transformative” victory for the U.S. — turned out to be a massive bust.

The deal, it may be remembered, required China to make $200 billion in new purchases of agricultural and manufactured goods, services and crude oil and other energy.

The idea floated by Trump was that the deal would end the trade war he had started with China, while producing a massive infusion of new income for American manufacturers and growers.

Today the only undisputed ‘historical’ aspect of that agreement is its failure.

— Chad P. Bown, Peterson Institute for International Economics

None of those outcomes happened. Although the trade war stopped escalating, most of the tariffs Trump had imposed on Chinese goods remained in place, as did retaliatory tariffs China imposed.

More to the point, “China bought none of the additional $200 billion of exports Trump’s deal had promised.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That’s the finding of a study just published by Chad P. Bown of the Peterson Institute of International Economics, who has assiduously tracked China trade since the deal was reached.

Trump called the deal a “historical” agreement — and even bragged that China would buy not $200 billion in new goods and services but $300 billion. As Bown writes, however: “Today the only undisputed ‘historical’ aspect of that agreement is its failure.”

In the end, Bown calculates, China bought only 57% of all the exported goods and services it had committed to purchase under the deal, “not even enough to reach its import levels from before the trade war.”

If you’re looking for more evidence that Trump’s vaunted negotiating skills were a sham from the start, there you have it.

It’s proper to look back at the trade atmosphere that prevailed when the deal was announced, and the skepticism that met the deal from the start.

Hiltzik: Trump’s China trade deal doesn’t even get us back to square one, despite immense cost

President Trump has declared victory in the trade war with China -- but America has paid all the price.

Trump launched his trade war under the influence of Peter Navarro, an intensely anti-Chinese economist on the White House staff. He consistently proclaimed that the tariffs would cost China billions, but that notion was ridiculed by trade experts, who were virtually unanimous in concluding that they’ve been paid entirely by Americans.

A paper issued in 2019 by trade economists from the Federal Reserve and Columbia and Princeton universities reported that the trade war was costing the U.S. economy $1.4 billion a month by the end of 2018.

That was the consequence of higher prices for U.S. consumers, lower manufacturing growth and the cratering of agricultural exports, all driven by Trump policies.

American exports to China fell because of retaliatory tariffs imposed by Beijing on more than $110 billion in goods, such as steel, aluminum and agricultural products.

The farm economy was profoundly harmed; for example, purchases of soybeans by China, formerly the leading export partner of U.S. soybean farmers, fell to zero in November 2018. The Trump administration announced roughly $28 billion in emergency aid to farmers affected by the trade war — another bill falling on U.S. taxpayers.

The tariffs covered Chinese-made parts needed by U.S. auto manufacturers, which increased the price of the vehicles exported to China. To circumvent the costs, manufacturers including Tesla and BMW moved production out of the U.S. and into China.

Even after the agreement, the average U.S. tariff on China imports remained at about 19.3%, more than six times its level of 3% before Trump launched the tariff war.

China hasn’t come close to meeting the commitments on trade it gave Trump in January

There were always doubts that China could absorb imports on the scale that the deal called for. The arrangement required China to import $52 billion in oil over two years. But the country was then importing about $8 billion a year in crude oil, liquefied natural gas and other energy products from the U.S. Experts were dubious that Chinese energy imports could more than triple, considering that the country has other import sources and was trying to develop domestic exploration. In any event, soon after the deal’s announcement, oil industry leaders told Trump’s aides they couldn’t provide products at the level the deal required.

An unanticipated factor contributed to the deal’s failure, Bown writes: the pandemic, which struck both countries about the time it was announced, shutting down both economies and cross-border trade. The pandemic shuttered the tourist trade, a major component of China’s pledge to step up service purchases. Business travel fell by 90%.

“The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic undermined any chance of success,” Bown acknowledges.

It was not the only factor. Others included the relocation of U.S. auto manufacturing to China and elsewhere to avoid the tariffs. The collapse of U.S. aircraft sales in the wake of the 2018 and 2019 crashes of Boeing’s 737 Max airliner also contributed.

But China was never on track to meet its commitment — a fact that both countries probably knew at the time of the deal.

In the end, however, it turned out worse than even some of its doubters expected. Trump’s trade war was disastrous for the U.S. almost any way one calculates.

Bown reckons that the trade war caused export losses of $119 billion from 2018 through 2021. That’s not counting the higher prices American consumers had to pay for imported goods, parts and raw materials, along with the farm subsidies.

In the final analysis, Bown writes, Trump did succeed in setting the U.S.-China trade relationship “on a new path.” But not the right path. “Nearly four years later,” he concludes, “different terms for the trade relationship are still needed.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.