What Jeff Bezos’ intimate-message breach teaches us about digital security

- Share via

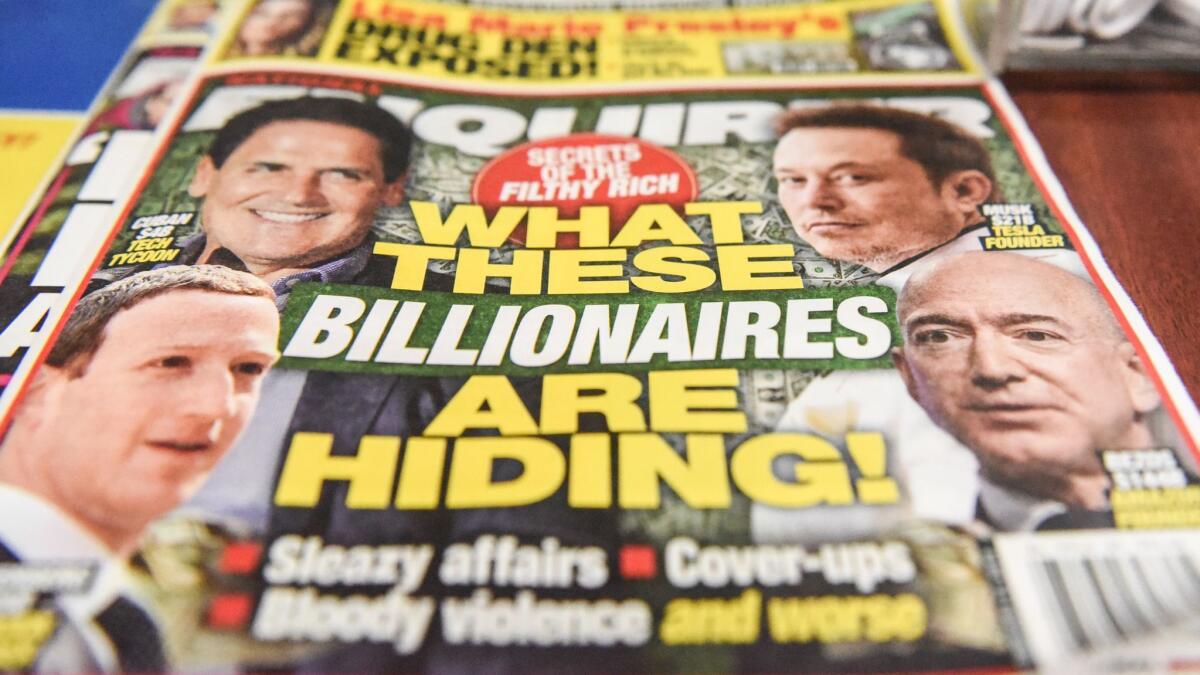

Last month, the National Enquirer shared the intimate texts that Jeff Bezos — Amazon founder, Washington Post owner and richest man in the world — had sent to Lauren Sanchez, a former television host, over the course of their months-long extramarital affair.

“I love you, alive girl,” the tabloid claims Bezos texted. “I will show you with my body, and my lips and my eyes, very soon.”

On Thursday, Bezos published a stunning accusation against the Enquirer’s parent company, American Media Inc., saying it threatened to publish compromising photographs, including a naked bathroom selfie, in order to coerce the billionaire into calling off an investigation into how the tabloid acquired his private communications in the first place.

Theories abound.

Gavin de Becker, who is leading Bezos’ investigation into the leaks, has said that he is looking into Sanchez’s brother Michael as a possible source of the “politically motivated” leak. Michael Sanchez — who has personal and professional relationships with Roger Stone and Carter Page, associates of President Trump — has fired back with a theory that De Becker himself worked to leak the information in an attempt to end the affair.

De Becker later told the Washington Post that Bezos was not hacked, but that a “government entity might have gotten hold of his text messages.” Bezos’ online post Thursday stopped short of alleging outright government involvement in the leaks, but it frequently mentioned American Media’s links to the Saudi government and the White House.

The Hollywood Reporter and gossip site Page Six, meanwhile, cited anonymous sources to suggest that the communications were simply leaked by friends of Lauren Sanchez.

The debacle has raised a more pressing question even for people who aren’t tech executives with professional security teams at their disposal: If Bezos can’t keep his texts and photos private, what chance do we have?

A determined assailant could take a number of higher-tech routes to extract private information from a phone. But the low-tech approach to invading someone’s privacy remains the simplest.

“I suspect that the most common way this happens is people send nude pictures or embarrassing text messages to other people, and those people save the pictures and send them to yet other people,” said Cooper Quintin, a senior staff technologist at the privacy nonprofit the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

No matter the method, though, there are some easy countermeasures people can take to ensure their personal communications remain personal.

One set of hacking tactics relies on accessing the device itself and installing snooping software that provides a way to remotely track what happens on the phone.

Quintin said the most common threat in this realm comes from “stalkerware” or “spouseware,” which is often marketed to suspicious spouses or concerned parents as a way to monitor a partner’s or child’s activity. These programs can take and send screenshots to snoopers, track and record calls and even turn on the camera and microphone to record what’s happening nearby (and are illegal in most circumstances in the U.S.).

Installing these programs requires physical access, and once they’re downloaded, they’re intentionally difficult to detect. The best defense is keeping phones nearby and password-protected.

Seemingly innocent apps downloaded via official channels can also serve as vehicles for malware, which could potentially be as invasive as any stalkerware. Quintin says most phone malware is more likely to be deployed to make a quick buck, whether that means stealing login info for banking apps, selling data to marketing firms or hijacking phones to mine cryptocurrency.

Stick to well-known apps, Quintin said, and keep phones updated with the newest version of their operating systems, which often contain patches to protect against new bugs.

A phone’s connection to the wider network can also serve as a point of entry for stealing private communication. Hackers can set up malignant Wi-Fi networks to snoop on data traffic. Mock cell towers — often referred to as Stingrays, the name of the most common commercial model — can intercept ingoing and outgoing messages and calls.

Luckily, the fix for this problem is baked into the most popular messaging apps: encryption. “Signal, WhatsApp, iMessage and a number of other messaging apps are all end-to-end encrypted,” Quintin said. “Even if you’re on a malicious Wi-Fi network or a highly advanced cell site simulator, they still can’t break good encryption.”

But the odds that anyone is trying that hard to steal your private messages is low, Quintin said — “99% of people don’t have to worry about this.”

Quintin also recommends using strong passwords and changing them regularly. If hackers can guess your cloud storage or email password (or find them in a past data breach), they don’t even need to interact with your phone to access your photos and messages. The hundreds of nude celebrity photos leaked in 2014’s massive hack were accessed with spear phishing attacks, in which hackers tricked celebrities into sharing their iCloud passwords.

Because the weakest link in any communication system — no matter how many zeroes you have in your bank account — is always the humans at each end.

“The person at the other end could always be screen-shotting, or writing down your text messages, or recording your call,” Quintin said. “Encryption is only as trustworthy as the person that you’re talking to.”

Follow me on Twitter: @samaugustdean