From paralyzed to PhD: A robotics engineer’s road to academic success

- Share via

Ryan Williams is smiling, as he always seems to be, and cracking jokes as his wheelchair rolls into the Bovard Auditorium at USC.

He one of the more 100 students from USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering in red graduation caps and gowns waiting for the start of the PhD ceremony.

His father, Clay, and brother Keith help adjust his billowy robe, making sure it stays tucked into the sides of the wheelchair. Unable to shake hands when meeting a stranger, Williams raises his right arm and extends his partially clenched hand in greeting.

“It’s a fist bump,” he says, laughing. “It’s all I’ve got.”

As the event, known as a hooding ceremony, begins, Williams waits patiently until near the end, when it’s his turn to get in line for his big moment on stage. This is only his second visit to USC since the accident more than six years ago that left him mostly paralyzed from the neck down and nearly derailed his dreams of a career in undersea robotics research.

But Viterbi’s Distance Education Network, along with the growing ease of connecting virtually, enabled Williams to steer himself back on to a path toward fulfilling that goal. Although such an accident might have left him isolated a decade or more ago, Williams has instead amassed a research and publishing track record that is already making waves in the field and has him on track for a likely academic appointment sometime in the next year.

Just as important as the technology, though, was what friends and family say is Williams’ remarkable will. All his life, Williams has had an ability to see the positive even in catastrophic moments that might crush the spirits of most people.

“I never really felt that bad about it,” Ryan says now of his life-changing accident. “I never felt depressed or really worried. I never had thoughts like, ‘I’m never going to do engineering again.’ It just felt like a switch had turned on and now I had this new life.”

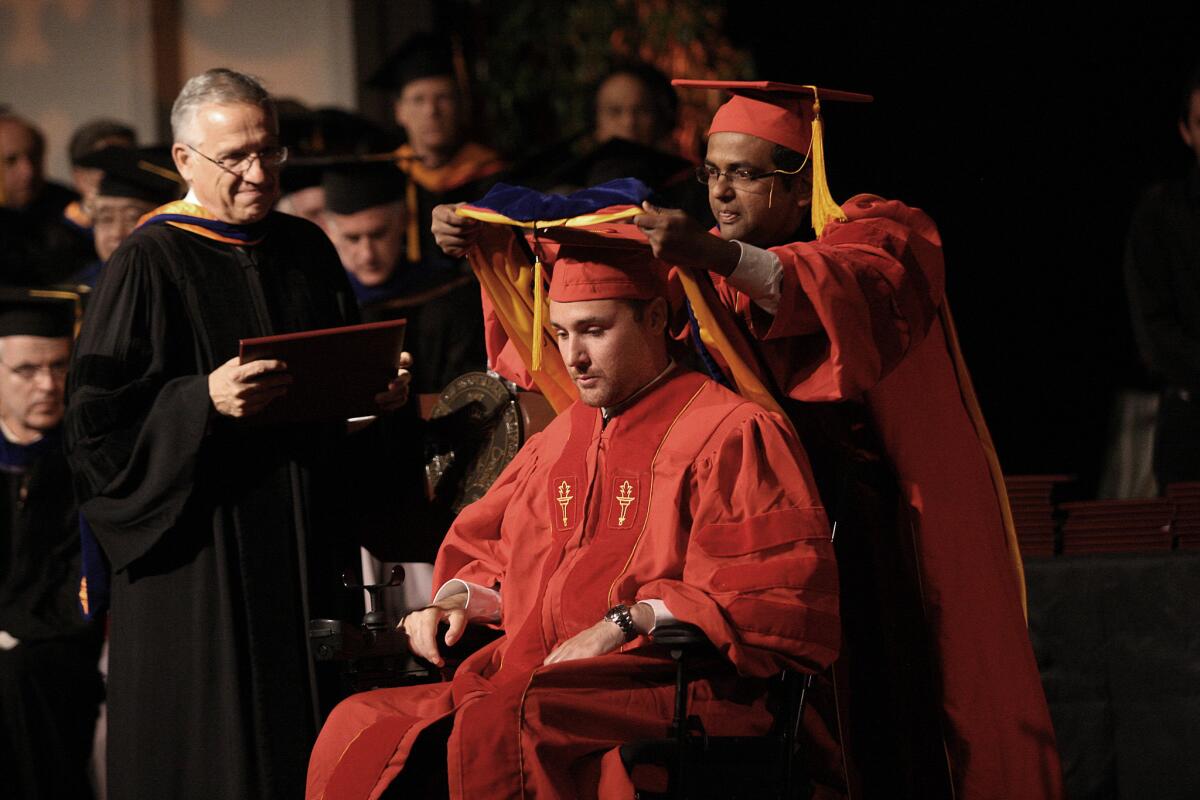

Finally, Williams’ name is called. He nudges a controller forward, moving his electric wheelchair to the center of the stage. He swivels to face the audience. The polite applause that greeted each candidate before him now swells in appreciation as the blue hood is draped around his neck.

Probably only a few people in the auditorium know the whole story of Williams and what it took to arrive at this moment.

“It’s very exciting,” said his father, surveying the sea of red robes stretching across the auditorium. “All the physical challenges he’s had every day. I’m so proud of him. The best part is that I’m really excited about what the future holds for him.”

In the beginning

Growing up in Roanoke in the southwest corner of Virginia, Ryan Williams was the oldest of three brothers.

He was pitcher for the high school baseball team. Star basketball player. Handsome, just over 6 feet tall and brown haired. Popular with girls. Scary smart. Impossibly blessed.

Although those qualities may have defined him in the eyes of others, they didn’t capture what made him truly special. His youngest brother, Keith, felt his unique presence growing up. The boy would turn to him for inspiration and advice of all kinds.

“When we were kids, he was an amazing brother,” Keith Williams said. “It was very easy to look up to him. He’s always had this ability to take bad things that might affect other people and be so positive. There’s never been a time when I’ve heard him complaining about anything that happened to him.”

After high school, Ryan Williams enrolled at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (a.k.a. Virginia Tech) in Blacksburg in 2001, 45 miles from his hometown.

He had already shown an intuitive sense for technical subjects, even as a child spending hours alone building fantastic creations out of Legos and Lincoln Logs.

At Virginia Tech, he gravitated toward the school’s Bradley Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, where he became fascinated with the research being done into autonomous underwater vehicles -- that is, underwater robots.

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, more than 300 miles from the ocean, Virginia Tech is an unlikely place for pioneers of underwater robotics. But the school is one of a handful under contract with the U.S. Navy to build and test such devices.

Dan Stilwell, a Virginia Tech engineering professor, said he and a team of graduate students built various prototypes and then would drive 30 minutes southwest of campus to test them in Claytor Lake, a sprawling 4,500-acre body of water.

Williams became an important part of the research team even though he was only an undergraduate. Although less experienced, he wasn’t one to sit around and wait for instruction. He saw what needed to be done, and he did it.

“What was really neat was that he was able to do that without a lot prompting,” Stilwell recalled. “There’s all sorts of smart. Some smart isn’t very useful. He was always very useful, on top of things. He was a very hard worker.”

Williams contributed ideas to the robots, helped design the experiments and analyze data. He also embraced the physical aspect of the field research.

He had long loved the water, and testing the underwater robots allowed him to spend hours on a boat deploying them. Williams would hold a slender, 3-foot-long robot over the side and fire it into the water like a missile. Later, he’d dive in to observe and retrieve it.

“That was the impetus for getting into scuba diving,” Williams said. “If anything goes wrong, it’s your job to get in there and make it right.”

The recovery

The accident in January 2008 caused Williams to break cervical vertebra 5 on his spinal column. He lost all movement from his chest down.

A couple of weeks later, Geordan Winners, a childhood friend from Roanoke, visited him in the hospital for the first time. Winners steeled himself for what he would see before finally entering the hospital room.

“I walked in and he was making jokes and had everyone in the room laughing,” Winners said. “He was mentally lifting the rest of us up.”

In typical fashion, Williams says: “In a lot of ways, you could consider me lucky.” Because, he says, some people with the injury spend their life on a ventilator and need care 24 hours a day. He wouldn’t. But there was also no fixing it. So he would move forward, as always.

“It’s one of those things where the universe is spun in a certain way, and you have what you have,” Williams said. “That helps me deal with it.”

Williams made an immediate, practical decision. The kind of physical work he had done, building and testing robots, was out of the question. He would focus on the theoretical aspects of robotics of how groups of undersea robots interact with one another.

Even as physical rehab was beginning, when Williams was just practicing blowing air through a straw, he started discussing logistics of continuing his studies with colleagues at Viterbi.

For several years, the school had been developing its Distance Education Network, known as DEN@Viterbi. By the time Williams arrived, the system had grown quite sophisticated, moving beyond its roots as a system to broadcast recordings of lectures to become an immersive, fully interactive experience.

DEN has become a vehicle primarily for enabling corporate students to earn a master’s degree from the prestigious Viterbi school. But for Williams, it proved to be a lifeline back to his old life.

Binh Tran, executive director of DEN, said the focus of the system is not to maximize the number of participants, but rather to simulate as closely as possible the human interactions that would take place if the person was sitting in the classroom.

“There can’t be a reason the technology is inhibiting any of the interactions,” Tran said. “The focus is on making it really engaging and interactive. It should be just like that person is right there in the room with everyone else.”

DEN limits the number of participants, not for technical reasons but rather to enhance the interactivity. Inside the classroom, an array of high-definition video cameras stream the classroom from multiple angles. Monitors on the professor’s desk and around the classroom show the faces of the remote students, enabling the conversation to flow between students near and far.

From the garage at his parents’ home in Roanoke -- which they gutted and converted into a work space -- Williams could access these sessions through his Web browser and a Web cam.

“There’s no excuse not to be able to do this,” Williams said. “It’s made no difference being at home, with all the communication tools I have. I don’t really feel that disconnected.”

Still, progress was frustrating and slow.

Williams’ injury caused extreme fatigue. Getting out of bed can take him as long as 90 minutes. Williams eventually regained some limited use of his arms. He can put his hand in a brace with a pencil attached, which enables him to tap one letter at time on a keyboard.

The pain can still be intense, but he avoids painkillers that might cloud his focus.

Easily exhausted, he could take only one class each year until he finally completed his coursework. Two years ago, he flew to USC for the first time since his accident to take his oral qualifying exams.

Meanwhile, he also made strides in his research. He runs computer simulations at home on his computer to explore the way groups of robots interact. And he talks via Skype with a team of Italian researchers who test his theories in the field.

Gaurav Sukhatme, chairman of Viterbi’s department of computer science and a world-renowned roboticist, has been William’s PhD advisor. He said Williams’ effect on the field has already been remarkable, and that his reputation among his peers is growing.

Williams has had four papers accepted into conferences, and in the last year he has been asked to present at conferences in Germany, Italy and Hong Kong.

“He’s able, even in the greatest moments of challenge, to grab the opportunities that are available,” Sukhatme said. “He’s intellectually gifted, but so are most students here. What’s exemplary about Ryan is ability to focus on his work and run with it.”

Preparing to head west

That Williams had this kind of intellectual potential was never in question to those who knew him at Virginia Tech. And that he had the drive was never in doubt.

As Williams neared undergraduate graduation in 2005, the future seemed limitless.

“We knew he was going to do well no matter where he went,” said Stilwell, the engineering professor.

Then came a setback. Williams wasn’t accepted into any of the graduate programs where he’d applied. It surprised most everyone at Virginia Tech.

So Williams stuck around the university for another year, got another year of research under his belt, and reapplied. This time, he was accepted by USC’s Viterbi school.

In the fall of 2006, Williams moved to California, driving across country with Winners and his brother Keith.

“I met him when he first got to campus,” said Sukhatme, one of the biggest academic names in robotics. “I was quite impressed with everything he had done as an undergraduate.”

Williams began his coursework and, later, his research. The field was moving fast. Big advances were being made as researchers found ways to build artificial intelligence and more sophisticated computing into underwater robotic vehicles.

It was an exciting moment. And Williams was right in the middle of it.

Williams also found that Southern California life suited him. The weather, the sunshine. He golfed. He skied.

Best of all, the boy from the Blue Ridge Mountains was excited to be living so close to the beach.

“A lot the research we do involves being in the water,” Williams said. “I loved the idea that I would be living near the ocean.”

The accident

On the day of the accident, Jan. 27, 2008, Williams stood on Santa Monica Beach with some friends.

The California water was chilly as always that Sunday afternoon. Williams was wearing his wet suit. Ready for a session of body surfing.

Williams dived in. His head slipped beneath the surface. Then his chin struck something hard, hidden in a sand bar perhaps.

“It’s just a freak thing,” Williams said. “I cannot tell you how many times I’ve done that. I’d done it the day before. It’s just one of those things. It’s a lightning strike.”

His neck snapped. His body went limp. Had a couple of nearby surfers not pulled him from the water immediately, he probably would have drowned.

Williams was rushed to a hospital, where surgeons operated on him for 10 hours. Keith Williams received a call that night and began making travel plans.

Keith, who had followed his brother to Virginia Tech and was enrolled in his same major, arrived three days later. Ryan was still in the intensive care unit, but he was off his temporary ventilator.

This would be a life changer, Keith realized, although it would be several days and many tests before doctors gave official news about the extent and permanence of his brother’s condition.

Sitting next to his brother’s bedside and broken body, he worried that this burden would prove too great, even for him.

Then Ryan woke up, and Keith looked into his eyes and saw it was still there. That spark, that optimism. The thing that would enable his brother to make the long journey back

“We didn’t talk too much,” Keith said. “We kind of just looked at each other. Even from that first day when I saw him in the hospital, I could just tell. He was going to do whatever he wanted to do.”