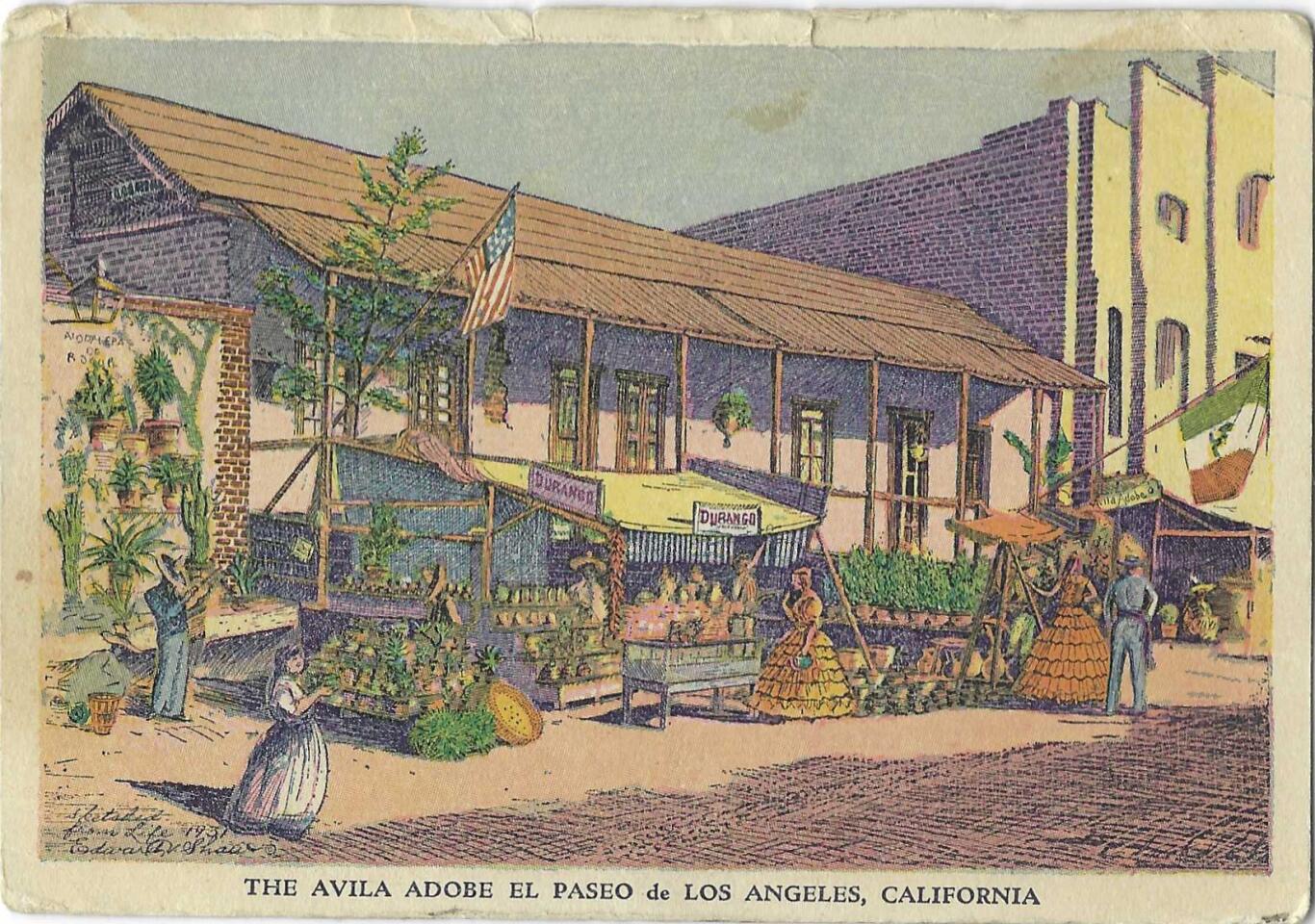

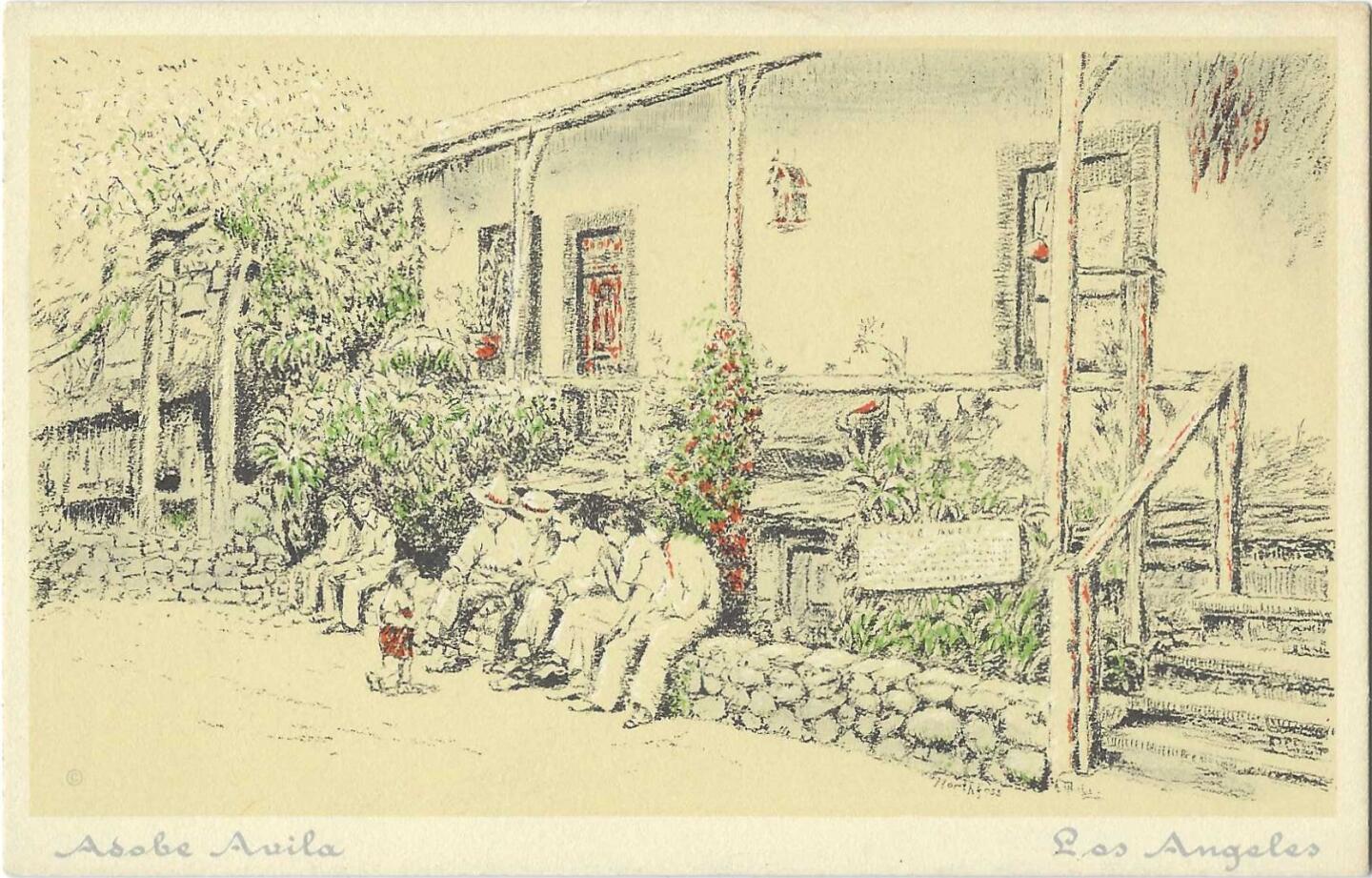

The reverse side of the previous postcard describes Olvera Street and includes a history of the Avila Adobe. The text concludes: “Truly it has been said, ‘here is all the picturesqueness of old Mexico plus the charm of historic interest.’” (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

The Avila Adobe was home to one of Los Angeles’ early mayors, Francisco Avila. The Avila patriarch came to Los Angeles in the 1780s and had five sons, one of whom was Francisco. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

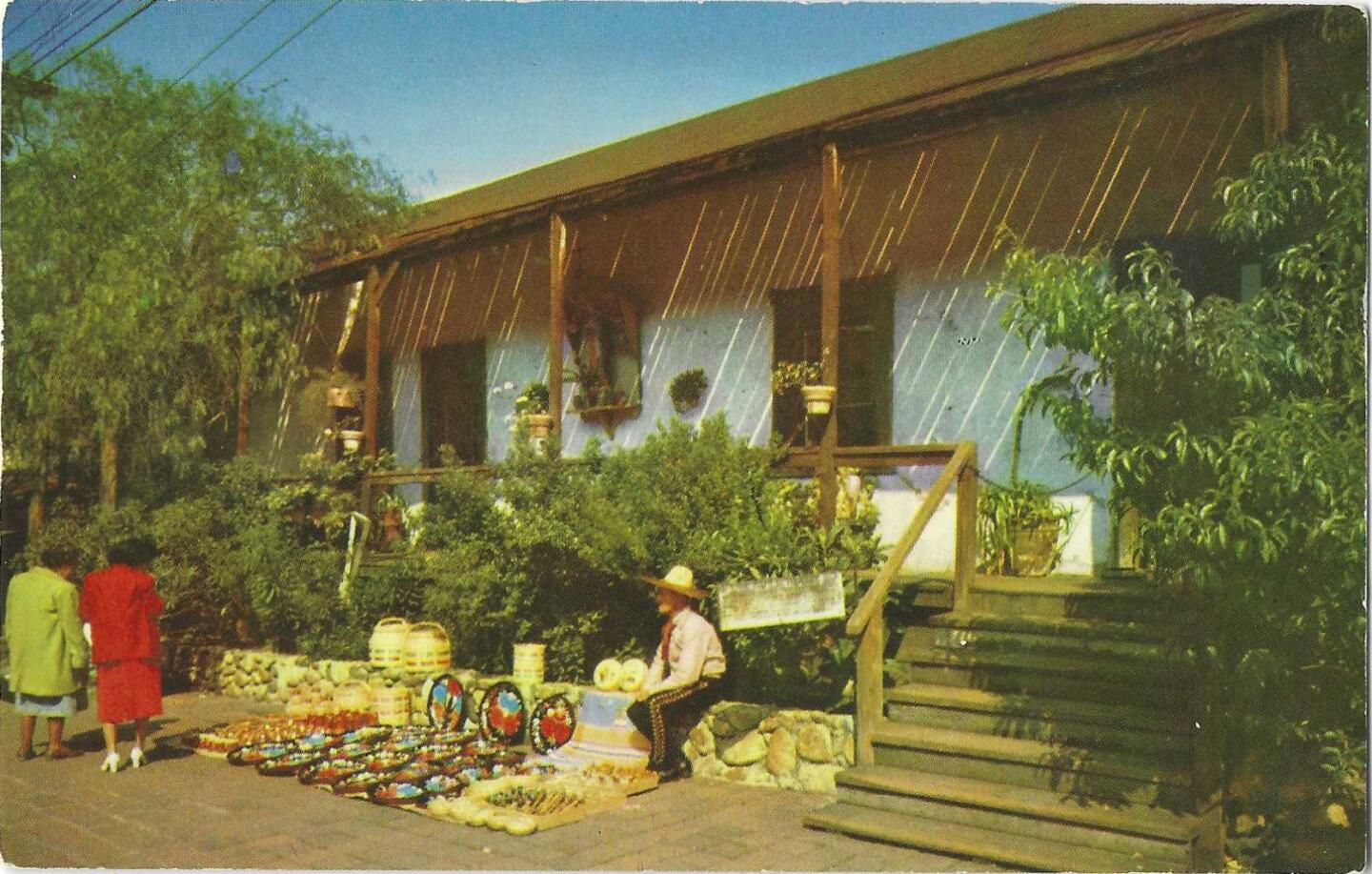

The reverse side of the previous postcard includes illustrations of L.A. landmarks. It reads: “Only one wing remains today of the 18-room mansion of Don Francisco Avila, early mayor of the pueblo of Los Angeles. This house was once used as headquarters of Commodore Robert Stockton when the American occupied California in 1847.” (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The Avila Adobe on Olvera Street is the oldest standing residence in Los Angeles. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

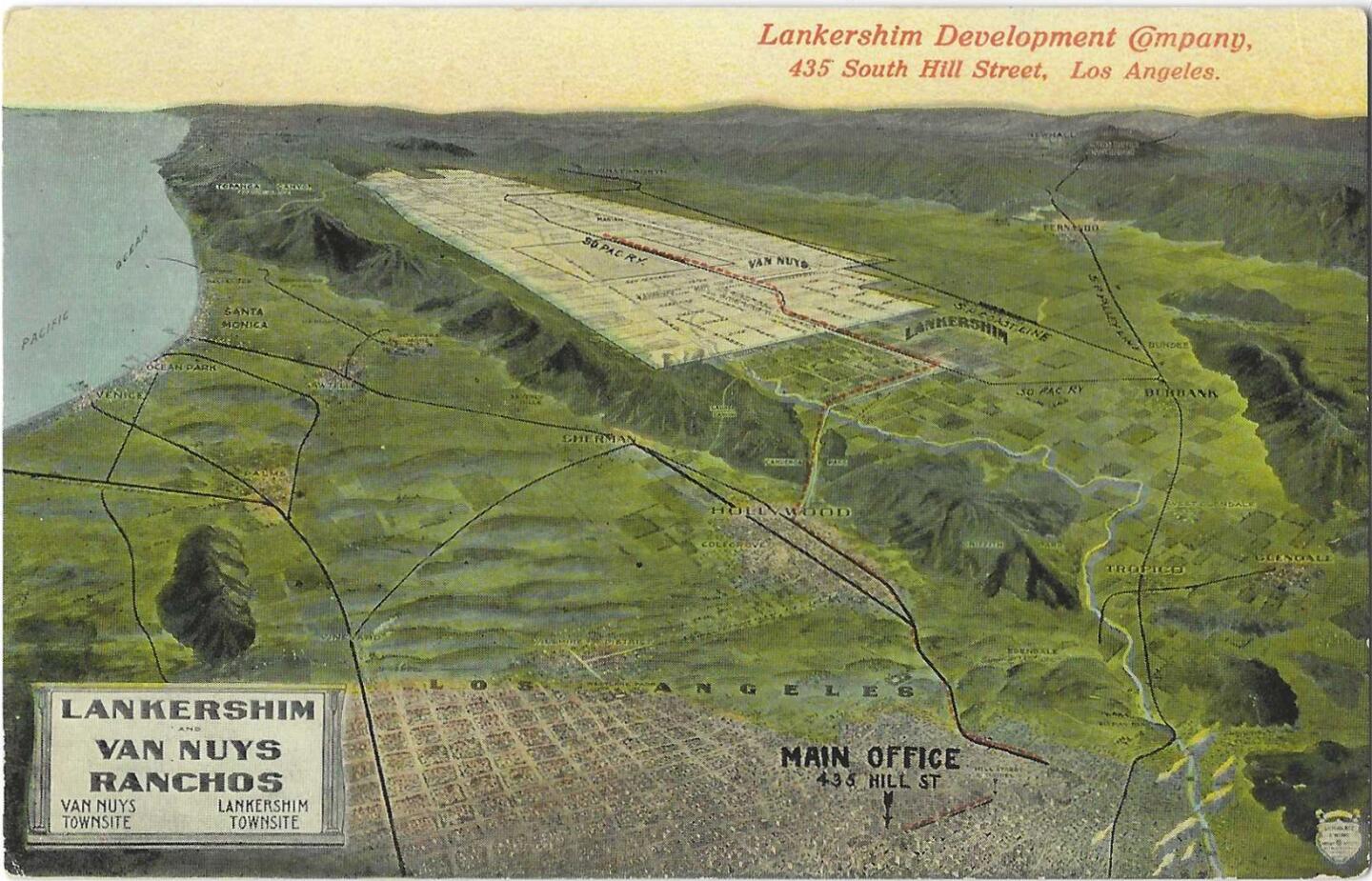

A realty promotion postcard from the Lankershim Development Co. shows the allure of L.A.’s lost history, with “Lankershim and Van Nuys Ranchos” for sale and a glimpse of the sites of now-vanished towns such as Tropico and Sherman. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

The “Balloon Route Excursion” advertised on the back of the Lankershim Development Co. postcard was a trolley car tour of far-flung places in Southern California. The one-day trip of marvels followed a balloon-like route and cost tourists $1. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

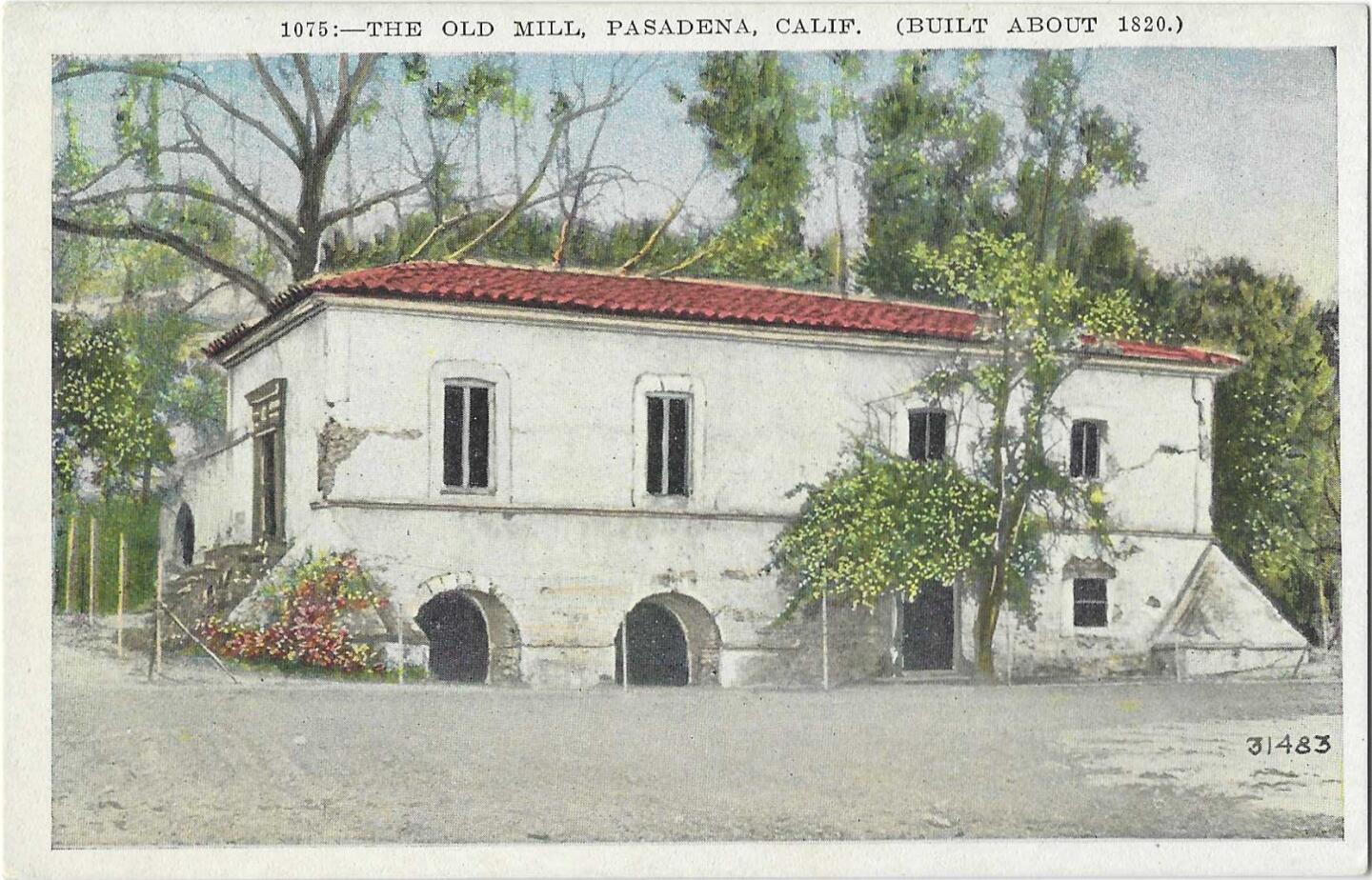

El Molino Viejo, or the Old Mill, in present-day San Marino was built about 1816 as a grist mill for the San Gabriel Mission. It’s now the oldest surviving commercial building in Southern California, and on the National Register of Historic Places. Its original millstones, lost for decades after the mill ceased operating, were discovered by none other than the future general George S. Patton. The Pattons were an early San Marino family, and young George, playing on the grounds of the Huntington estate, noticed a couple of unusual stones being used by riders as mounting blocks. They turned out to be the millstones.

(Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The reverse of the previous Old Mill postcard details the mill’s history, saying that its “operation was not a complete success due to the leakage of water used for power which made it impossible to store grain after it was ground.” (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

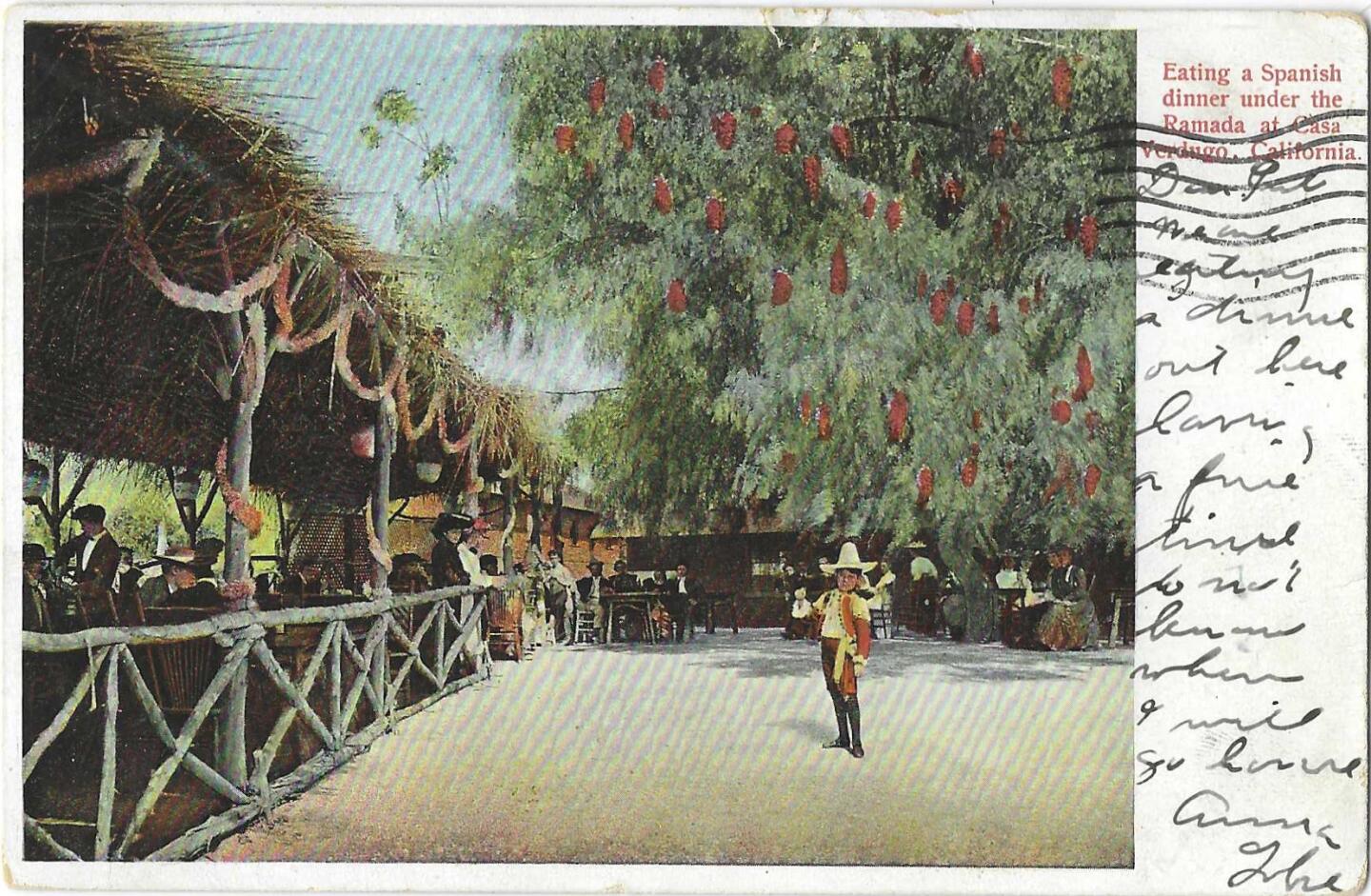

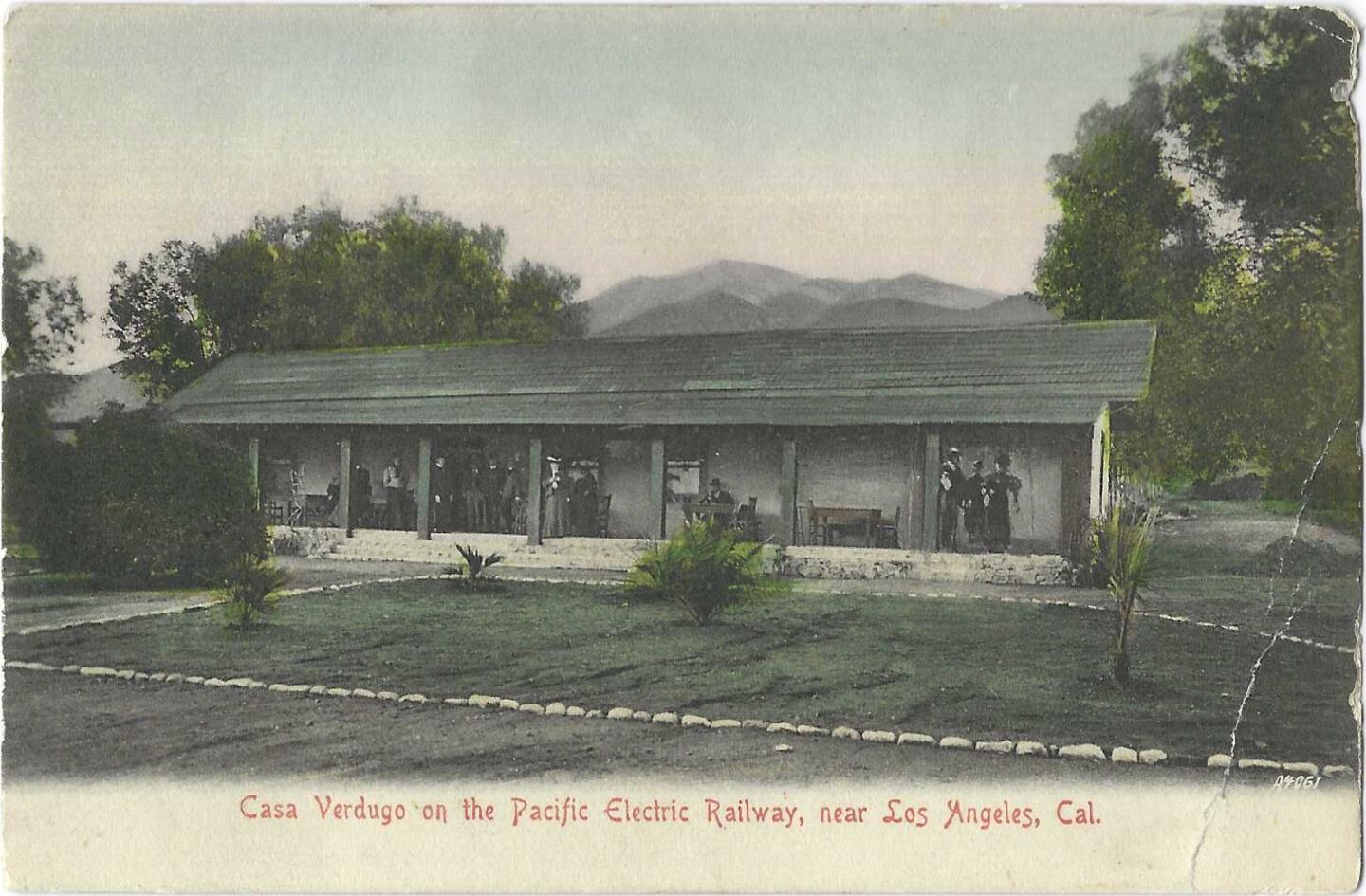

Around 1905, Pacific Electric built a line out to this 1860s adobe in what is now Glendale and opened a restaurant called Casa Verdugo. There, as the advertising text says, visitors could eat “a Spanish dinner.” (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Piedad Yorba Sowl, the restaurateur who ran Casa Verdugo and other eateries, was related by blood and marriage to several great rancho families. The adobe still stands on land that was granted in the 18th century as Rancho San Rafael. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

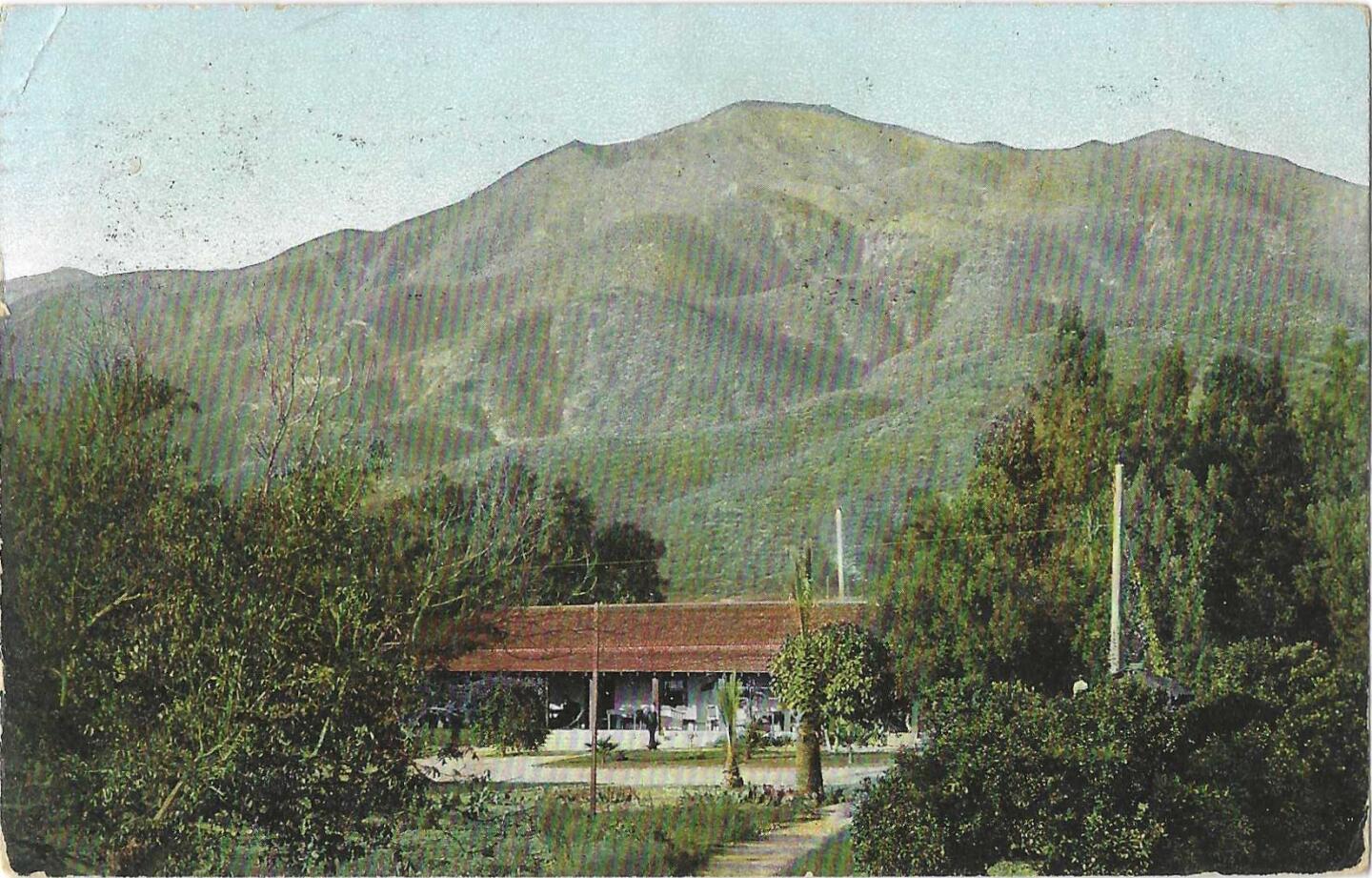

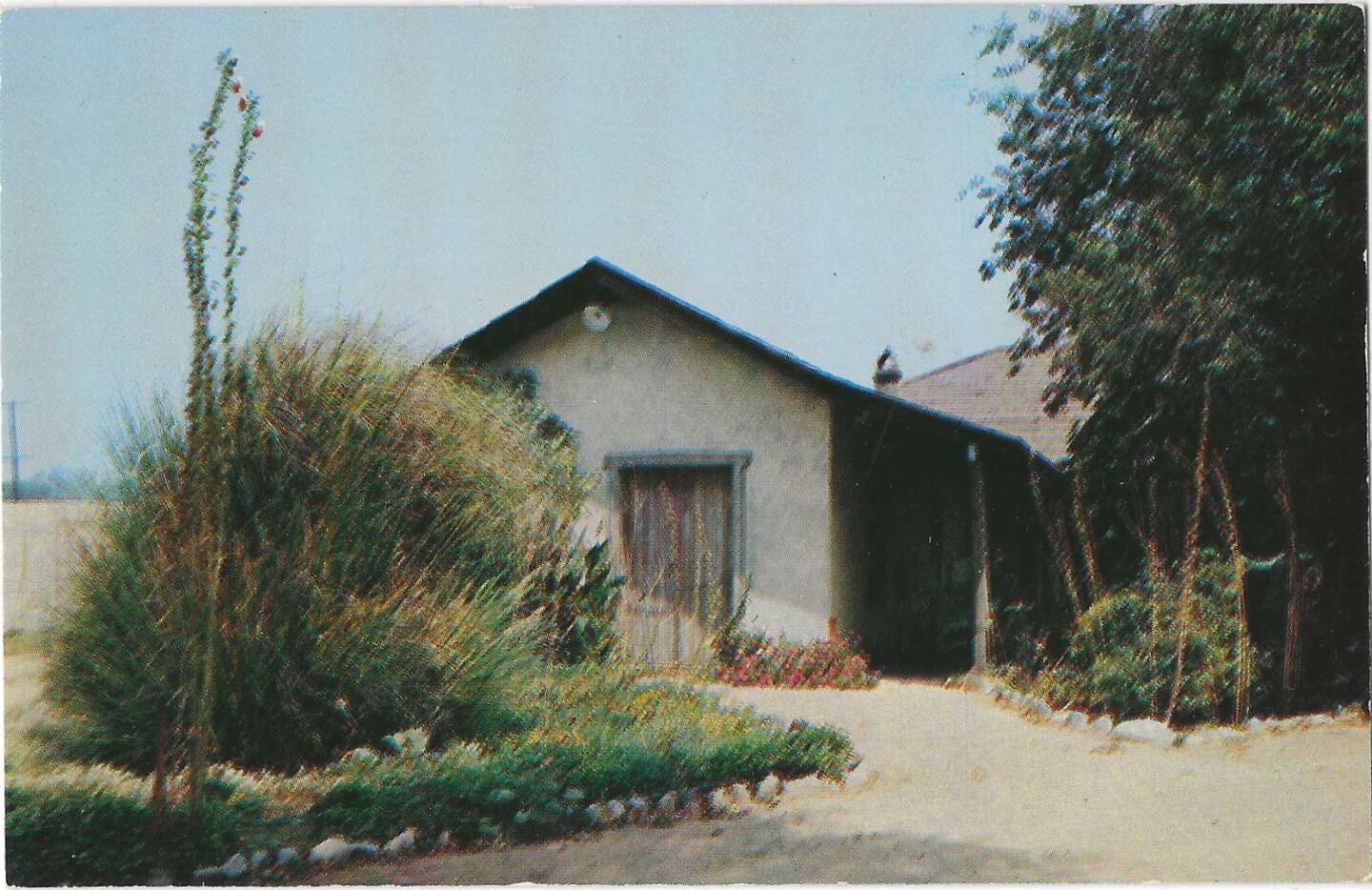

A landscape view of Casa Verdugo is depicted on this postcard. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

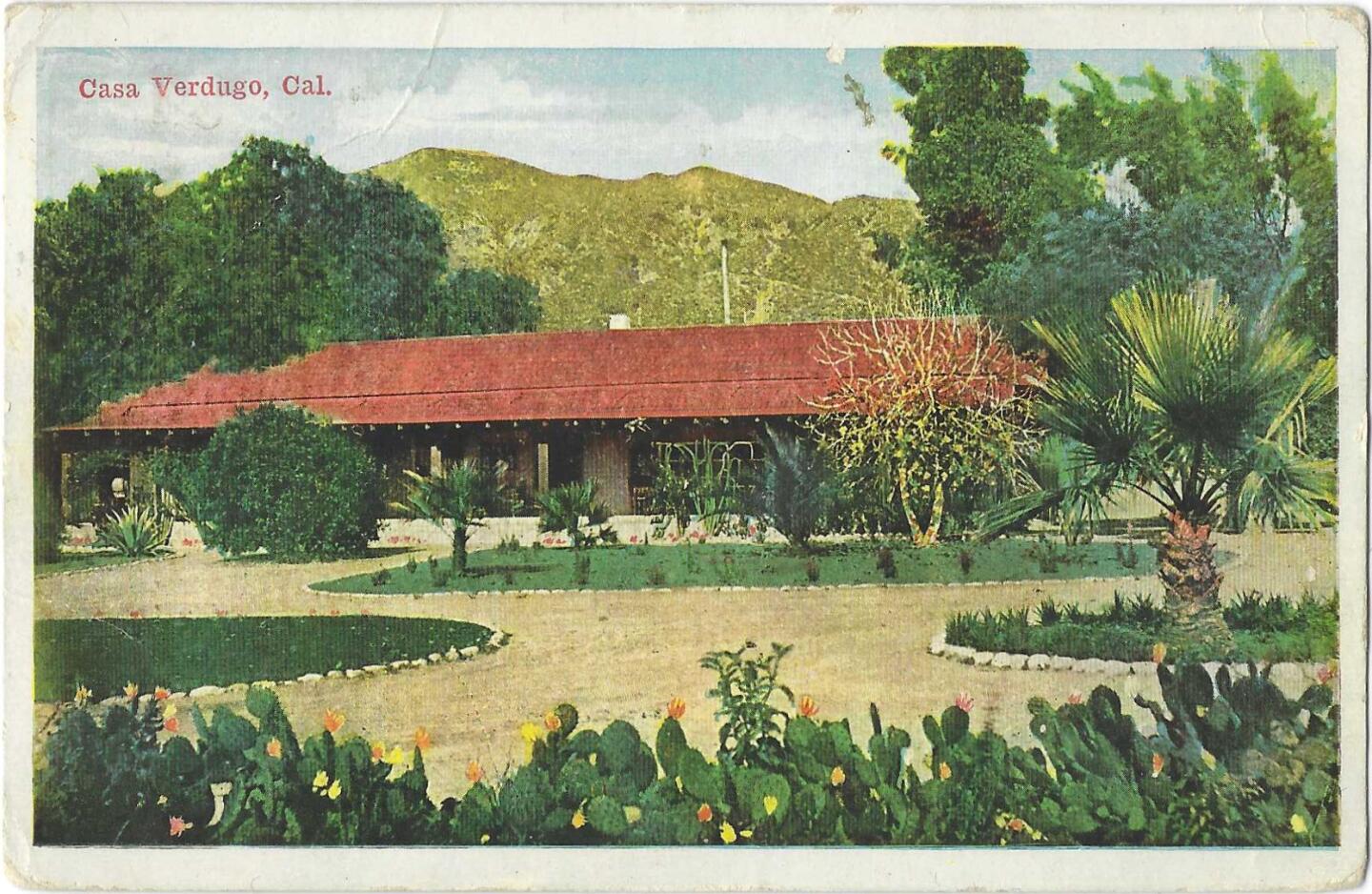

A vintage postcard depicts the cacti and other plants in the garden at Casa Verdugo, which is in present-day Glendale. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

In this vintage postcard, people can be seen standing on the Casa Verdugo porch. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Built between 1850 and 1855, the earliest years of California statehood, the Palomares Adobe stood on land that was part of Rancho San Jose, which was granted to the Palomares and Vejar families after the new Mexican nation dissolved the missions that had once owned the land. The adobe was the Palomares family’s second home on the property. Like so many pioneer adobes, it crumbled away to a ghost of itself before the city of Pomona took it over in the 1930s and began restoration work. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

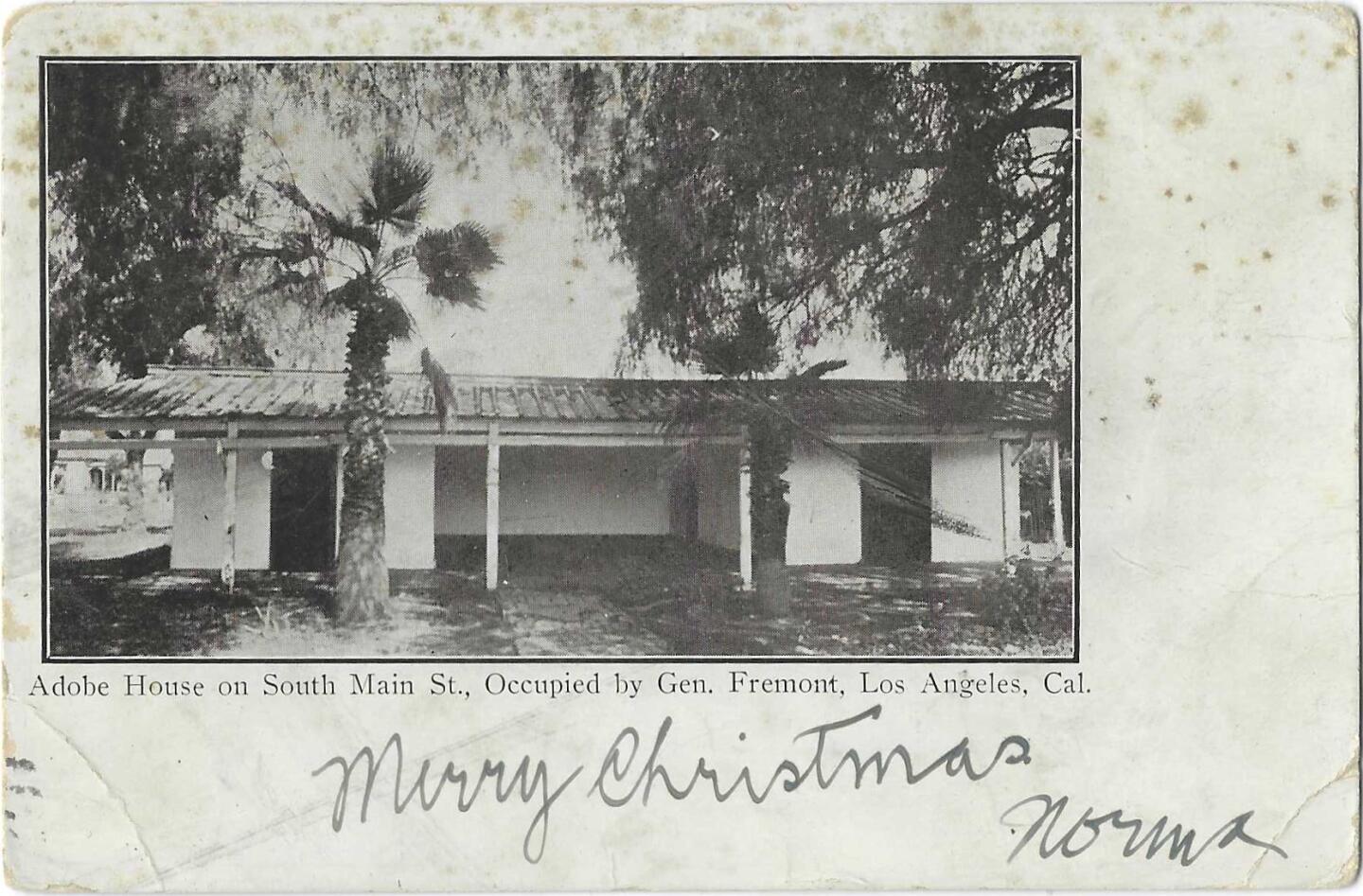

This tourist postcard touts a legend, not fact. Gen. John C. Fremont, the ardent self-promoting Army officer, politician and explorer of the West, did not live or keep his headquarters in this adobe on South Main Street. It was built in 1856 by future Civil War Union officer Henry Hancock. Before the war, Hancock was the surveyor for a number of rancheros establishing their legal claim to the land. Hancock became a ranchero himself, holding Rancho La Brea, site of the tar pits and much of future Hollywood and Hancock Park, and co-owning Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, now modern-day Beverly Hills. The adobe is no longer standing and is believed to have been near the corner of Main Street and what is now 14th Street. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Flores Adobe in South Pasadena was built between 1838 and 1845 on land that was part of Rancho San Pasqual. In 1847, it was where Californio general Jose Maria Flores gathered his military staff to discuss the language of the surrender treaty. The house thereafter was named for him. In the decades that followed, the adobe became a boarding house, fell into disrepair, was restored by a Pasadena socialite and is now on the National Register of Historic Places. (Patt Morrison / Los Angeles Times)