She vowed to upend the status quo. But voters chose a longtime City Hall aide for council

- Share via

Astrophysicist and college educator Loraine Lundquist ran for office with a promise to take on the status quo, saying she would shake up Los Angeles City Hall by ending “pay-to-play politics” and scrutinizing decisions with the eye of a scientist.

Lundquist’s bid for a seat on the City Council energized Democrats, environmentalists and progressive activists eager to win over a San Fernando Valley district long represented by Republicans.

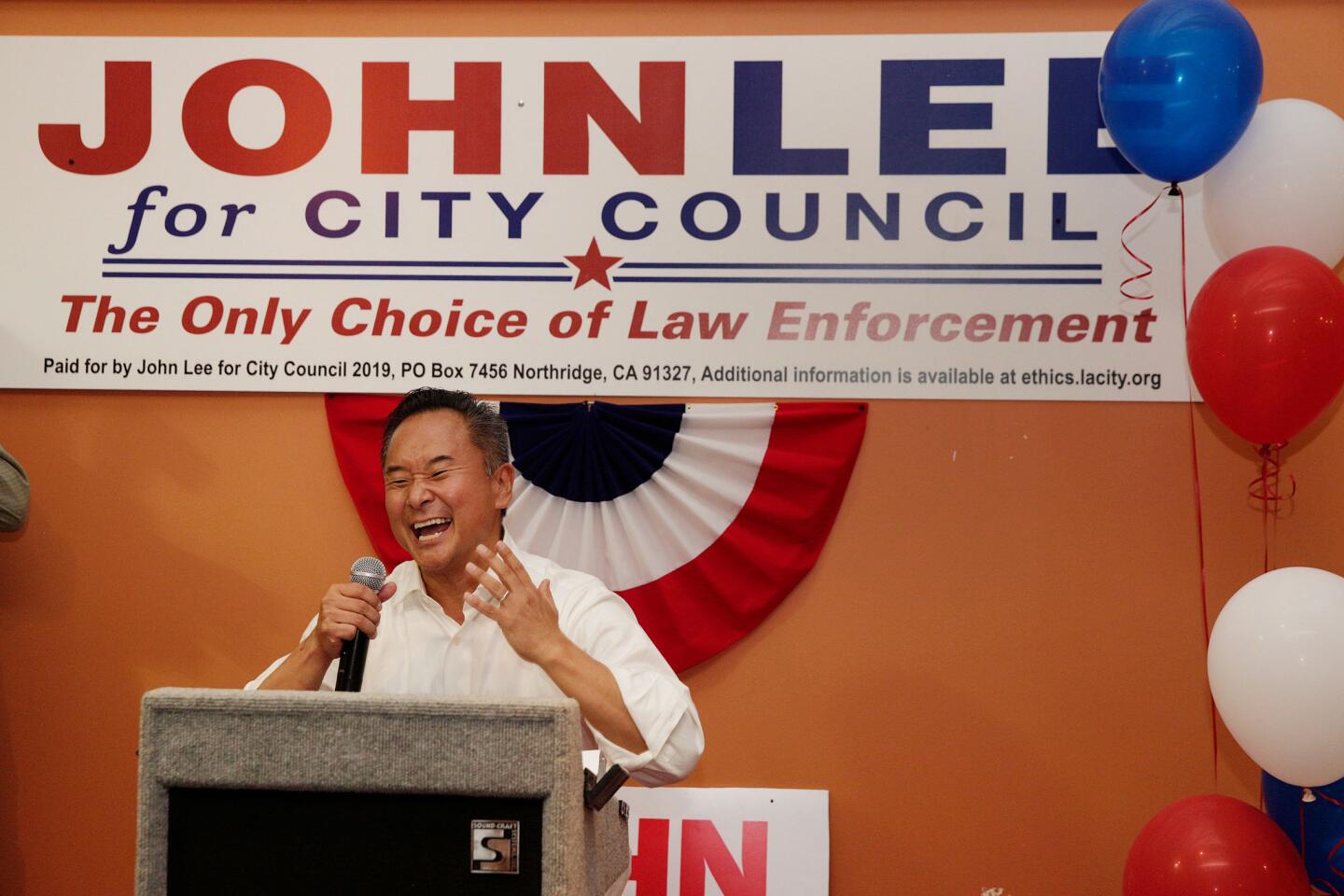

But Lundquist ran into a buzz saw of opposition from some of City Hall’s most experienced players, including business groups, the police officers’ union and former council members who represented the northwest Valley for generations. All lined up behind longtime City Hall aide John Lee, who emerged victorious Wednesday.

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 18, the combative union that represents most workers at the Department of Water and Power, ran an expensive campaign against Lundquist, calling her an “extremist” who would hike taxes, drive up electric rates and even force Angelenos to buy electric cars.

Lee, who worked at City Hall for two decades, attributed his success to his long history in Council District 12 and keen focus on neighborhood issues. His supporters argued that Lundquist had alienated voters by focusing on sweeping ideas like Mayor Eric Garcetti’s version of the Green New Deal, which is aimed at combating climate change and weaning the city off fossil fuels.

“He’s a community guy, and she’s too left-wing and too far out for this district,” said former Councilman Hal Bernson, who represented the district from 1979 to 2003 and supported Lee. “This new green thing, doing away with automobiles, this is all part of her mantra and I don’t think this district is ready for that.”

Lundquist supporters from across the city had argued that a victory for her campaign would represent a major win for political progressives, setting the stage for their candidates to compete in the March election, when seven seats on the council will be in play.

Many also argued that the Green New Deal and Lundquist’s environmentalist credentials were deeply relevant to the Valley district, the site of a massive methane leak at the Aliso Canyon storage facility.

Before Lundquist had even conceded, some of her supporters were calling for a rematch. Because this week’s contest was a special election, the winner will have to run for reelection seven months from now, when the presidential race is also on the ballot and a greater number of Democrats are expected to show up at the polls.

“We will have a chance to right this wrong in 2020,” Michael MacDonald, a Lundquist supporter and campaign volunteer, said on Twitter.

Lundquist said Wednesday that she has not decided whether she will make another run for the seat.

Lee, a Republican, had promised on the campaign trail to be a “different voice” on the council, someone who would not always side with the council’s politically liberal members. On Wednesday, he downplayed the partisan split in the race, saying he would be a model of “bipartisan representation” in a nonpartisan office and had already reached out to some of Lundquist’s supporters.

Lundquist campaign consultant Jesse Switzer accused Lee and his allies of campaigning on fear, saying they had made untrue claims about Lundquist and her political positions.

Many of those disputed claims revolved around Garcetti’s Green New Deal, which sets a goal for converting buildings to “clean power” and calls for 25% of the city’s motorists to drive electric or other zero-emission vehicles by 2025 and 80% by 2035.

Switzer said there was no factual basis for the claims, made repeatedly by the DWP union, that Lundquist would ban gas stoves or force people to buy electric cars. Garcetti’s plan envisions using incentives and rebate programs to nudge consumers to change their behavior.

“People were constantly asking us about baseless accusations,” Switzer said.

A representative of the DWP union did not comment. Lee, in an interview, disputed the idea that he or his supporters had engaged in fearmongering, saying he ran a “positive campaign about the community” that highlighted his years of work in the district.

Others argued Lee was more in sync with the district, pointing to his stances on homelessness and a planned bus rapid transit project that could potentially reduce car lanes. Lee opposed putting such a route on Nordhoff Street, one option being considered. Lundquist refused to rule out Nordhoff as a possibility, saying that she wanted more study of the issue.

Many homeowners feared that putting bus rapid transit on Nordhoff would clog the area with traffic and ultimately lead to upzoning of their single-family neighborhoods, either by the council or the state Legislature, said Lee supporter Steve Slutzah, vice president of the Sherwood Forest Homeowners Assn.

“We’ve lived in our home for 22 years,” Slutzah said. “The last thing we want to do is look out our backyard and see a four-story or five-story apartment building on what was an open space.”

Steve Ducey, a paid organizer who supported Lundquist, said the issue became so heated that he encountered voters who incorrectly believed that Lundquist would “eminent domain their home” for the bus project.

Lundquist also had a number of politically connected forces on her side, including the L.A. County Democratic Party, more than half of the members of the City Council, and Aaron Sosnick, a hedge fund manager who bankrolled mailers assailing Lee for his support from “dirty oil interests.”

Several council members rallied the crowd at Lundquist’s election night party in Chatsworth, saying they were eager to see a Democrat win the seat.

Lee registered as a Republican in 2015 and was listed in voting records as a Democrat as recently as 2013, according to a county election official.

He followed a familiar path to victory in the northwest Valley: He was the top aide to Councilman Mitchell Englander, who was in turn the top staffer to the previous councilman, who held the top job for the councilman before that.

Political experts say that Lee’s margin of victory — he had 52% of the vote, according to the unofficial results tallied Wednesday — shows that he could be vulnerable in the March election. But he will probably have a financial advantage as an incumbent in the next campaign, said Eric Hacopian, a political consultant who did not work with either candidate.

“And because so many more people are voting, the election becomes a hell of a lot more expensive,” Hacopian said.

Even though she did not face an incumbent, Lundquist was outspent in Tuesday’s race. One Lundquist supporter said he took heart that the contest was as close as it was in an area that is more conservative than other parts of the city on such issues as climate change and homelessness.

“If Loraine signs up for a rematch, we will rally,” said Walker Foley, a senior organizer with a political action committee that backed Lundquist.

Times staff writer Piper McDaniel contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.