California cracks down on fishing in protected areas, but anglers slip under the radar

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Cory Pukini wasn’t surprised when he spotted a pair of kayakers on a recent Friday morning illegally fishing inside a marine protected area off La Jolla Cove.

He’s been working with the nonprofit Wildcoast for three years and grew up fishing in Southern California — long before California’s network of marine protected areas, or MPAs, was dramatically expanded in 2012.

“You guys are inside of the MPA here,” Pukini said from the deck of a Boston Whaler that the conservation group routinely uses to monitor the protected areas. “We’ve got a wildlife and recreation guide to help you stay in compliance.”

Trina Williams of Tierrasanta happily accepted a laminated map of the state’s coast and its MPAs. “I thought I could just drop some line and catch the little Spanish mackerel,” said the 31-year-old from her kayak.

“I knew that it was protected because my husband, who’s teaching me fishing, said there’s this invisible line,” she added, “but you have to kind of guess where it’s at.”

In recent years, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has increasingly cracked down on commercial boat operators who escort passengers into MPAs to illegally catch everything from rockfish to bass to yellowtail.

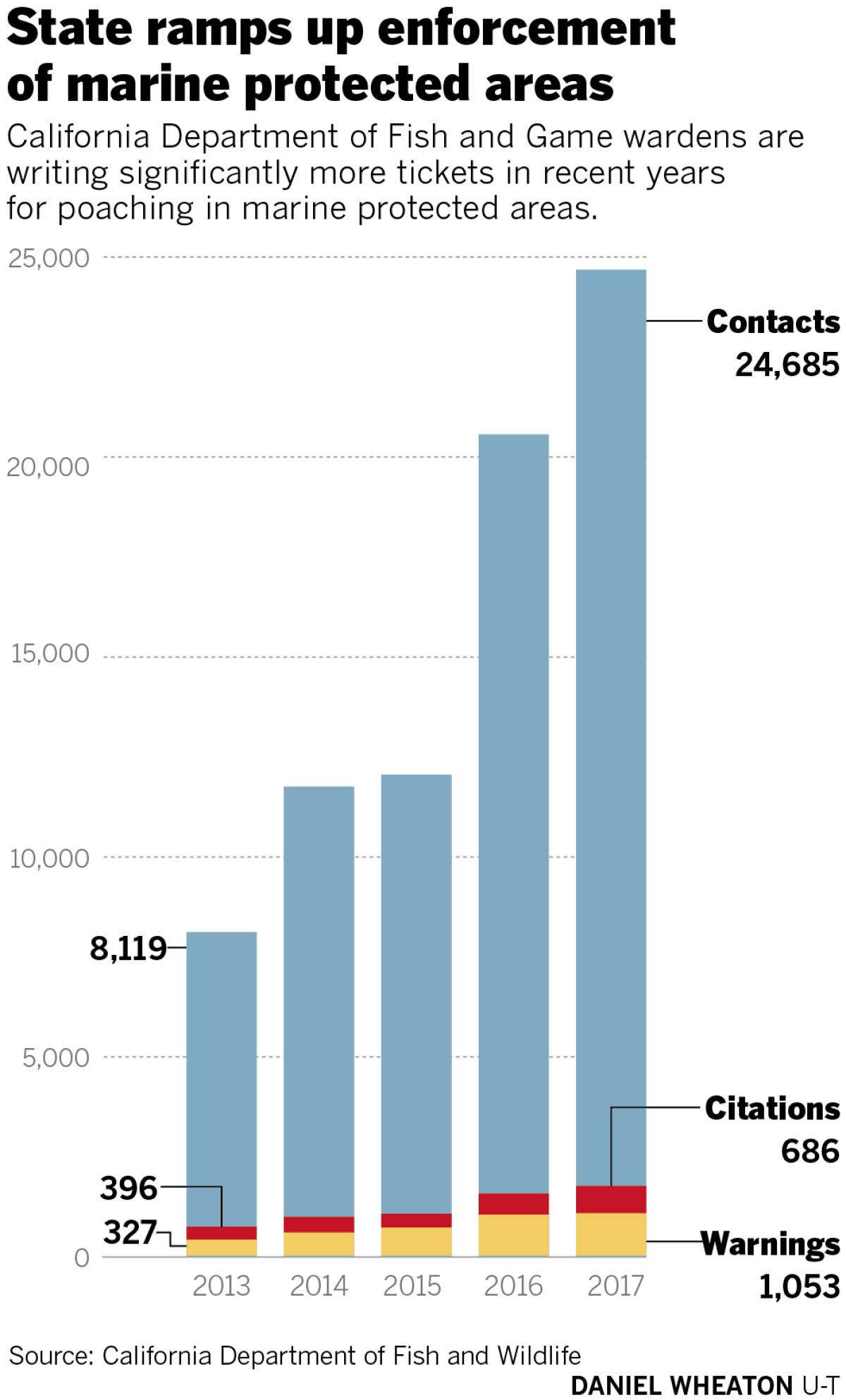

Wardens issued 1,053 warnings and 686 citations for illegal fishing in the protected areas in 2017, according to the agency’s most recently available data. That’s up dramatically from 2013, when wardens gave out just 396 warnings and issued 327 citations.

Advocates say authorities have over the last year continued to get even tougher on poaching in the state’s 124 MPAs, which cover about 16% of coastal waters or roughly 5,200 square miles.

Most notably, the Pacific Star Sportfishing charter boat had its license suspended for five years in February 2018 after a protracted legal process that started when undercover wardens caught the boat’s operator leading fishing trips into an MPA off the Channel Islands several years ago.

“It’s pretty simple. The sportfishing community doesn’t go in there anymore, and that’s that.”

— Ken Franke, president of the Sportfishing Assn. of California

Then in January, the state dramatically increased the fines for commercial poaching in an MPA, under a bill authored by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego). Charter boat captains and others turning a profit off fishing now face penalties of between $5,000 and $40,000 for a first offense — up from just $100 to $1,000. A second offense can result in a suspended license and a commercial operator owing the state up to $50,000.

“It’s pretty simple,” said Ken Franke, president of the Sportfishing Assn. of California, which represents charter boat operators. “The sportfishing community doesn’t go in there anymore, and that’s that.”

However, MPA advocates say a lot of illegal activity is slipping under the radar when it comes to recreational fishing. Folks casually angling from a kayak can still face fines of up to $1,000 for a single offense, but such tickets appear to be rare.

Pukini with Wildcoast said he regularly reports illegal activity, unwitting and otherwise, using Fish and Wildlife’s tip line: (888) 334-CALTIP. But, he said, wardens rarely respond.

It’s not hard to see why. In San Diego and Orange counties, for example, there are 18 separate MPAs, and the department has just one patrol boat and five marine-focused wardens to cover them all.

On any given day those wardens could also be responding to a boating accident, helping out with an oil spill, repairing agency vessels, filling out paperwork or any other number of tasks, said Mike Stefanak, assistant chief of marine enforcement with the department.

“Offshore enforcement of the MPAs is tough because it requires that you to be out there and you run a large patrol boat or a skiff fleet, which creates a lot of maintenance,” he said. “Can we be out there every day? No. Not right now.”

While it might not seem like a big deal to quickly drop a line into a protected area while heading away from shore, scientists are worried it’s having a collective impact on the health of the marine ecosystems.

The idea behind the MPA network was to create protected spawning grounds that help marine life rebound and eventually repopulate fishable areas. However, the more the protected areas thrive, the more alluring they are to anglers.

“It doesn’t take much illegal fishing to reduce the effectiveness of the reserves,” said Ed Parnell, a researcher at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography who studies the marine protected areas. “The jury’s out on [the success of] many of them, particularly in places like south La Jolla where there’s a lot of illegal fishing activity.”

Advocates for recreational fishing have acknowledged the situation but said that it’s been hard to adequately inform the public, especially in places such as San Diego, where a lot of tourists aren’t aware of the local rules.

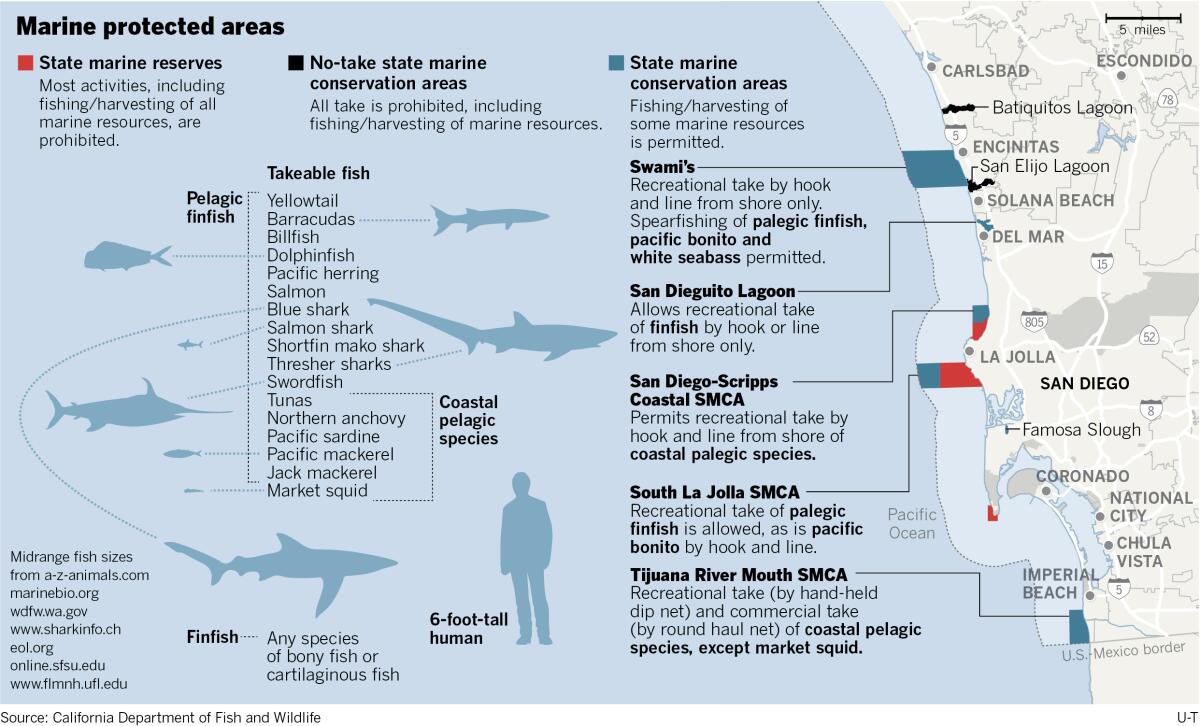

Part of the issue is that the restrictions can be complicated. Rules vary among MPAs, ranging from prohibiting any removal of marine life to the recreational take of only designated fish species, such as salmon, sardine, mackerel and tuna.

At the same time, the lines of any given MPA can be tricky to determine when boaters are on the water, especially for those just getting into fishing. Commercial operators can track their location using an electronic tablet, but those in a kayak may not have that luxury.

“We’re working on getting the word out to our guys, but how do you do that?” said Wayne Kotow, executive director of California Conservation Assn., a San Diego-based advocacy group for the recreational fishing community. “How do you know where the MPA is when you’re on the water? It’s an imaginary line. We are a tourist destination. People don’t know.”

One tool that’s helping the leisure fishing community is an app called Fish Legal. It shows a user’s location on a map of the coast that includes the MPAs and the rules for each protected area.

Another thing that could help crack down on the casual poacher is enlisting other agencies to help with enforcement, such as the Coast Guard, sheriff’s departments and local lifeguards.

That’s what Calla Allison has been working on. She’s the founder and director of the Marine Protected Area Collaborative Network, a group established with help from the state to bring together the fishing community, tribal representatives, government officials, nonprofits, scientist and others.

Allison was on the boat with Pukini that Friday snapping pictures of the MPAs from the water. She said the images would be posted online to help the fishing community more easily identify where the protected areas start and stop.

The photographs, she said, would also be useful in an enforcement training for local agencies scheduled for spring. She said she plans do the same for all the MPAs throughout the state in an effort to encourage more agencies to get involved.

“At the very least, we want them to be able to recognize, even if they’re not citing [someone], an egregious violation, so they can make contact and try to gain compliance,” she explained.

Just then, a couple of lifeguards on a patrol boat floated by. Allison quickly took the opportunity to ask them if they were aware of the MPAs and gauged their interest in being involved with enforcement of the protected areas.

After a quick exchange shouting over the rumble of the ocean, she asked them if they understood what she was talking about.

“It’s clear as mud, like everything else the city does,” one of them said smiling.

“Hopefully we’ll make it simpler and clearer soon,” Allison called back. “We’re looking forward to working with you guys.”

Smith writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.