Gov. Newsom, you can be a coastal access hero. Meet me in Gaviota, and we’ll kayak to Hollister Ranch

- Share via

When Gavin Newsom was elected governor, he became chief steward of the most spectacular coastline in the world.

Now he’s about to take his first big test, on a coastal access bill, and I can help him study.

For the record:

9:05 p.m. Sept. 11, 2019A previous version of this column misspelled Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard’s last name as Chouniard.

As I told his chief spokesman Tuesday, all Newsom has to do is meet me at Gaviota State Park and we’ll paddle up to Hollister Ranch in a couple of kayaks. The trek can be dangerous, as I learned last year, but that’s the point.

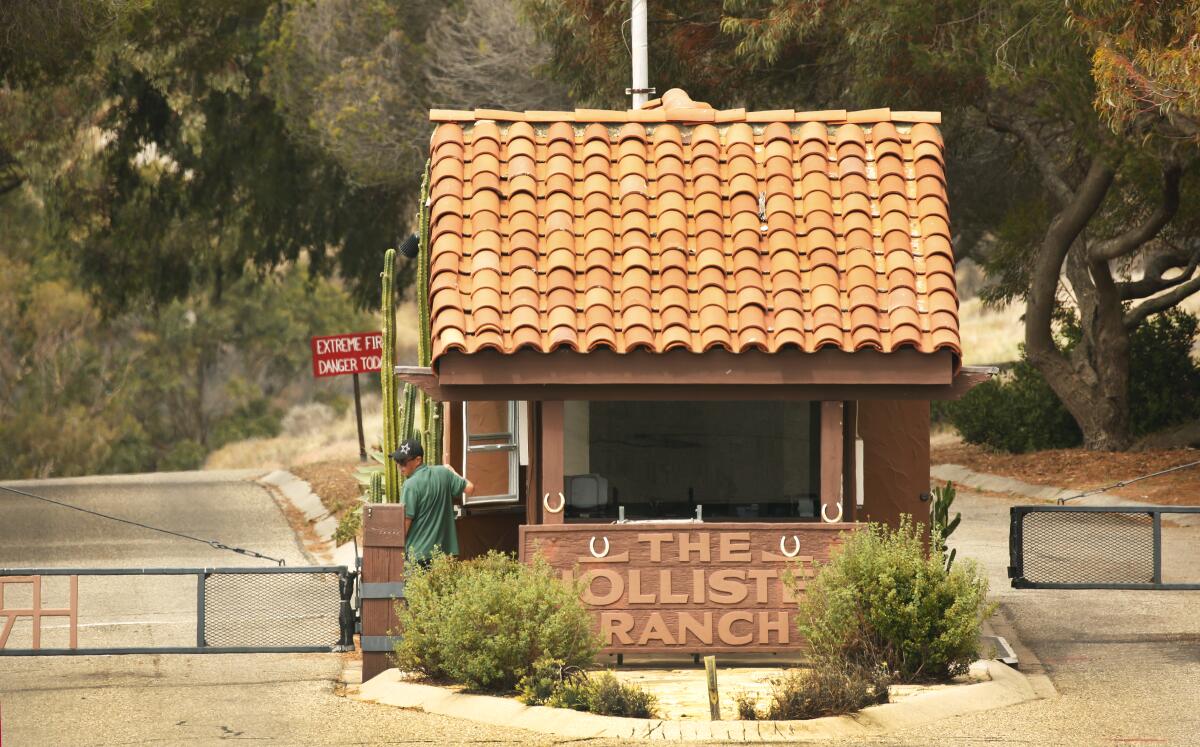

For about four decades, residents of the exclusive ranch above Santa Barbara have done everything in their power to keep you and me off the beach. And when the state slapped us in the face last year by striking a rotten deal to allow strictly limited access, including by kayak, the public fumed.

After more than 2,000 Californians blasted the agreement in emails to the California Coastal Commission, a judge put a hold on the deal. Assemblywoman Monique Limón (D-Santa Barbara) then crafted a bill — AB 1680 — that has sailed through the Assembly and Senate with nearly unanimous, bipartisan support, as reported by my colleague Rosanna Xia.

The bill would allow access by land to a small portion of the ranch and some of the 8½ miles of beaches, and on Wednesday the Coastal Commission voted unanimously to reiterate its support for the bill.

But nobody seems to know whether Newsom will sign it, even though his spokesman told me coastal access has been a high priority for the governor ever since he served on the state Lands Commission while he was lieutenant governor.

Let’s hope his commitment is high, since he’s likely to get a lot of pressure to keep the public out.

There’s been some buzz in Sacramento about the Hollister Ranch Owners Assn. hiring a lobbying firm — Axiom Advisors — earlier this year. Why the buzz? Because Axiom has two principals who worked with Newsom before he was governor.

An attorney for Hollister told me the lobbyists were hired “to give some advice” about Limón’s bill, but the job was done and the lobbyists “are not working for Hollister right now.”

OK, but there’s a long history of Hollister using cash, clout and connections to keep the hoi polloi at a distance. And to hear one resident tell it, the fight is far from over, new legislation or not.

“Apparently Ms. Limón thinks that with this bill she can somehow open the gate and get people into the ranch just by a legislative act,” said Kim Kimbell, a lawyer and longtime Hollister resident who serves on a legal committee at the ranch.

Kimbell said forcing access would constitute a “taking” of private property, and that would require the state to buy the land.

“So if this is basically an effort to start an eminent domain proceeding, so be it,” said Kimbell. “But that’s what it’s going to take to get possession of any sort of our private property.”

When I shared Kimbell’s take with Limón, she said she was neither surprised nor deterred. The dispute has existed for decades, she said, but the public outcry last year resulted in a bill that was hammered out with input from community groups and four state agencies under Newsom’s control.

“I was born and raised in Santa Barbara and always heard about Hollister Ranch but never had a chance to go there,” said Limón. “I didn’t know anyone who lived there that could invite me in.”

Every time I’ve written about Hollister, I’ve heard from people who wonder what I don’t understand about the words “private property,” or from those who say the state has plenty of easily accessible beaches for the public to enjoy, so why harp on Hollister?

First of all, California has long recognized that the coast is a natural treasure, and that it should be accessible to everyone rather than only to those who can afford to buy beach property.

The state Legislature, the state Constitution and the landmark Coastal Act — which resulted from a citizen uprising after attempts to privatize the Sonoma coast and plop a nuclear power plant at Bodega Head — have all codified the public’s right to get to the beach.

That doesn’t mean we can trample all private property rights. It means a balance must be found, and that the right to develop coastal property comes with a requirement to allow limited public access. Hollister residents have not held up their end of the bargain, even though, as Ben Welsh and I reported last year, they reap huge property tax breaks under an agricultural preservation law because a cattle ranch operates on the land.

Speaking of which, another argument from Hollister residents is that, thanks to them and their locked gate, this one stretch of coastal property is environmentally pristine and must be kept that way, so stay out.

Never has the term “B.S.” been more apt.

The residents have been known to drive vehicles on the beach, one or more high-rolling resident has used the ranch as a heliport, and running a poop ranch doesn’t sound to me like the best way to protect the environment.

When the first rains wash the manure into the sea, I’d like for residents James Cameron, Jackson Browne and Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard to take water samples and call me with the results.

“The ‘pristine’ argument is frankly ridiculous and elitist,” said Marce Gutiérrez-Graudiņš of Azul, a nonprofit organization focused on coastal conservation and access. “It purports that the public is too unwilling or uneducated to [care for] the coast. Only people with access to multimillion-dollar homes are able to.”

Hollister was required to provide beach access as early as 1979, said Susan Jordan of the California Coastal Protection Network. In 1982, in response to residents’ foot-dragging, the Legislature stepped in again, but met with more resistance.

“So for four decades, the Legislature has been clear, but what we’re dealing with is a very recalcitrant entity,” said Jordan.

“I believe some people in Hollister Ranch will continue to hold out as long as they can afford to fight, but there might be some others in Hollister who believe maybe it’s time to move forward,” Jordan said. “I’m looking to those people to step up, and for the governor to be the governor of all the people … and not just some.”

There you go.

Newsom has a chance to do what his predecessor Jerry Brown couldn’t.

He can be the patsy of a few or a hero of the many.

And if he’d like to talk it over, I’ll have the kayaks geared up and ready to go.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.