More than 400 UCLA medical school students get a free education thanks to major donation

- Share via

Medical school had put Allen Rodriguez in debt before he was even accepted.

The testing, applications and interviews alone cost Rodriguez thousands that he’s still paying off on his credit cards. So it was a relief — and a deciding factor — when his 2014 UCLA medical school acceptance came with more good news: a full scholarship, funded by a $100-million gift from billionaire David Geffen.

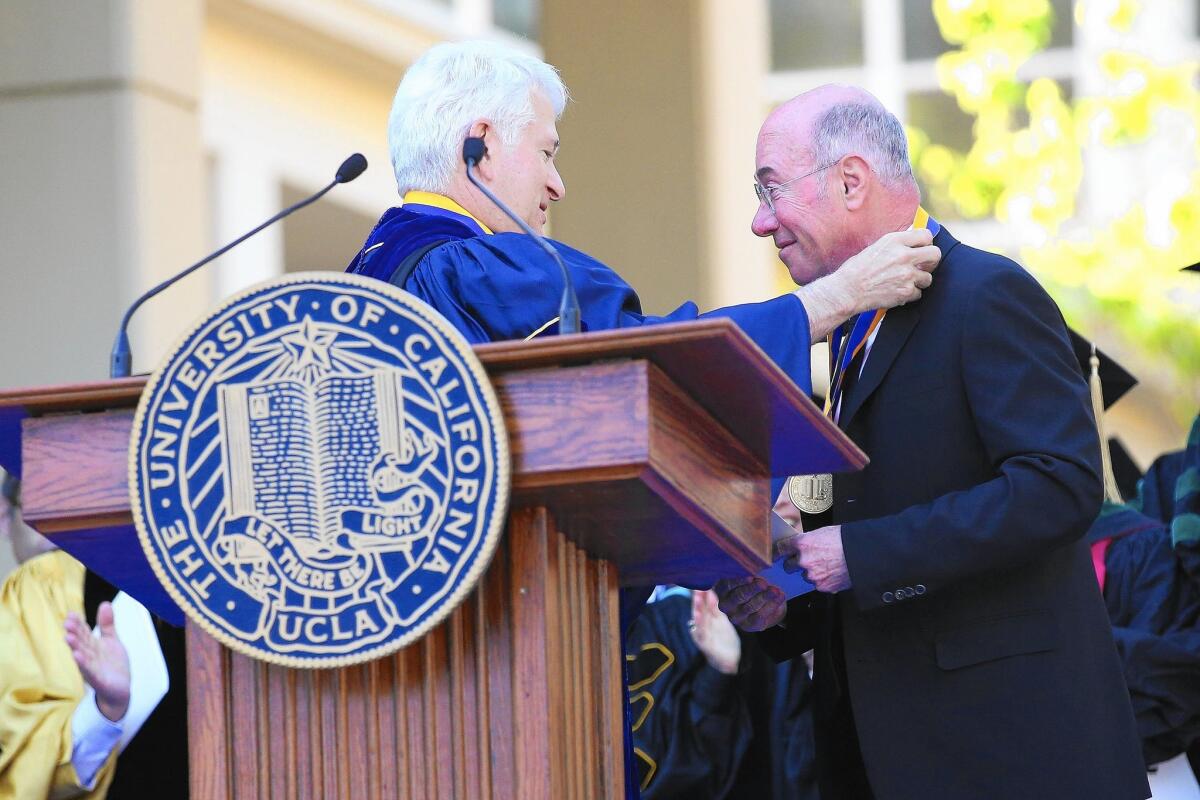

The UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine announced Monday that the DreamWorks co-founder, who gave the school $100 million in 2012, has donated an additional $46 million to continue to fund merit-based scholarships so medical students do not have to take on weighty loads of debt. His UCLA donations total nearly half a billion dollars in the last two decades, much of it to the medical school.

The scholarships cover tuition and expenses, and students are told of the award when accepted to the medical school. The school expects that the $146 million will fund 414 scholarships — 20% to 30% of each class for a decade, ending with the class of 2026.

For Rodriguez, the scholarship meant he could focus his time in medical school on finding “what’s going to make me happy, not necessarily what’s going to make me money,” though he realizes he will earn more than his parents ever did regardless of specialty. The 32-year-old doctor, who graduated last year, is in his second year of residency at Scripps Mercy San Diego, in a family medicine program that offers training for doctors in both English and Spanish.

Last year, 75% of U.S. medical school graduates had accrued debt that averaged almost $200,000, according to an Assn. of American Medical Colleges survey of graduates from 150 medical schools. For California residents, tuition and fees alone at UCLA’s four-year program cost upward of $42,000 annually.

Free from the financial burden of his education, Rodriguez said, he helped raise money to fund scholarships for undocumented medical students at UCLA and advocated for statewide policy changes that would make undocumented medical students eligible for loan forgiveness.

He still has some debt, though — about $20,000 from his undergraduate years at UC Berkeley, plus about $10,000 in credit card debt and loans accumulated mostly from applying to medical school and residency programs.

“It takes so much money and time to apply that many people are priced out of it,” Rodriguez said. Medical students do tend to have higher-income parents who are more likely to have college degrees, according to surveys from the Assn. of American Medical Colleges.

Rodriguez’s parents did not attend college. Now retired, his mother owned a sign company and his father worked his way up from a warehouse job to middle management at Raytheon Co. They had some savings to help fund college, but Rodriguez and his three siblings were largely on their own. He believes diverse life experiences like his help create a workforce that can better understand and treat patient needs.

“The Geffen Scholars program is life-altering for our students and their future patients,” Dr. Kelsey Martin, dean of the Geffen School of Medicine, said in a news release. “Mr. Geffen’s generosity has remarkable ripple effects.”

Although many recipients like Rodriguez do need the financial aid, Geffen’s gift could be more socially beneficial if scholarships were based on need rather than merit or if they encouraged recipients to treat underserved communities for a period of time, said Phil Buchanan, president of the nonprofit Center for Effective Philanthropy and author of the book “Giving Done Right: Effective Philanthropy and Making Every Dollar Count,” which offers advice on donating.

“The competitive pressures among institutions of higher education have led them to emphasize merit aid, because they’re trying to win in a competition against each other rather than thinking about what is best” for society from an equity and opportunity standpoint, Buchanan said.

Geffen declined to comment on the donation via a university spokesman. The medical school bears his name after a $200-million gift in 2002, and in addition to this scholarship he donated $100 million in 2015 to start a private school meant in part to serve the children of UCLA faculty members.

UCLA is not the only school to seek out large donations for its medical students. Last year New York University’s School of Medicine announced that it was raising $600 million from private donors to cover tuition for all students.

Most medical school students who gain acceptance have one to three schools to choose from, said Geoffrey Young, senior director of student affairs and programs for AAMC. As a former admissions committee member at three schools, including the Medical College of Georgia, he said, “If we could use scholarship money to entice someone to come to that school, I would. That’s a free market.”

Geffen was clear that he wanted to use merit-based scholarships to attract the best potential doctors to the school, said UCLA Health Sciences Vice Chancellor Dr. John Mazziotta. Other students do have access to need-based scholarships, and Mazziotta said his ultimate goal is to start an endowment that would fund UCLA medical school for all students “forever” — an endeavor that would take upward of $1 billion, he said.

Rodriguez said he would still have pursued medical school without the scholarship — but probably not at UCLA. He might have found a program in a city with a lower cost of living, or would have chosen a M.D.-PhD program, which takes double the time to complete but offers more funding for students.

And although family medicine is among the less lucrative specialties, Rodriguez feels he has made the right choice.

“I just want to go where the need is high and where my work will make a difference,” he said, “where if I wasn’t there, it wouldn’t be as good.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.