Wine country’s iconic Jimtown Store forced to close by fires and blackouts, owner says

- Share via

It had seemed like a bit of much-needed good news when the Kincade fire tore through Sonoma County’s Alexander Valley this fall.

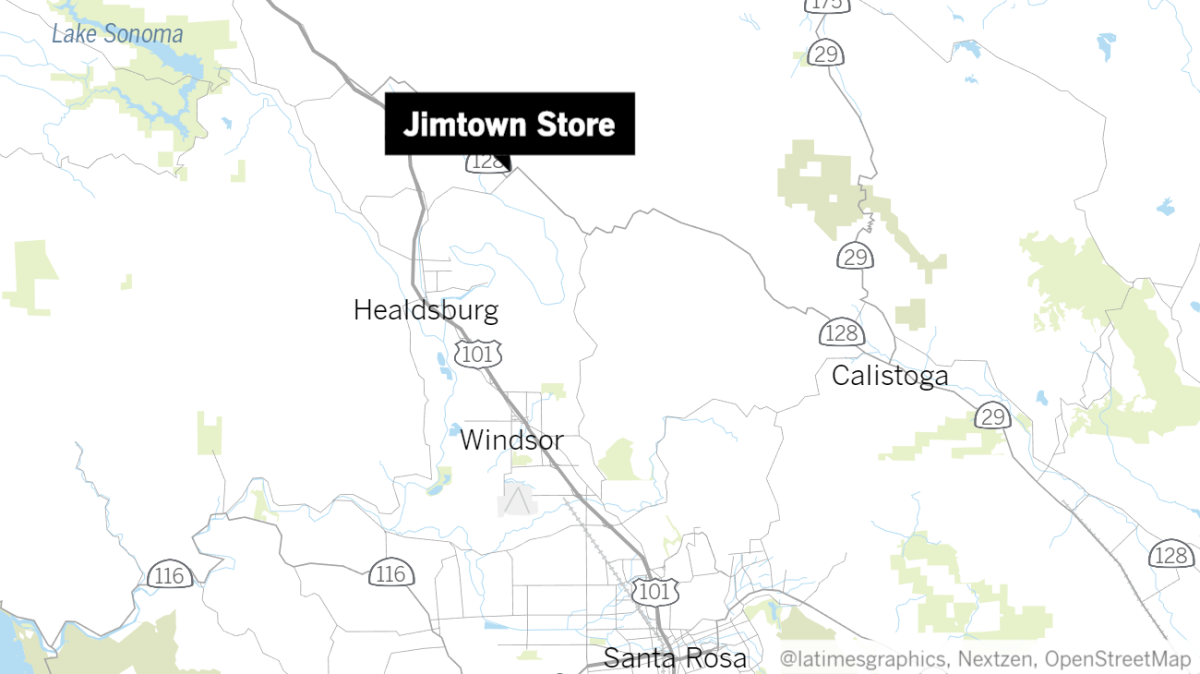

The beloved Jimtown Store, a cafe and old-time mercantile on rural Highway 128 that had been around, in some form or another, since the 1890s, had survived the late October flames. Just a mile and a half up the road, the historic Soda Rock Winery lay in ruins, its ashen image broadcast around the world.

“We’re still standing!” Jimtown Store owner Carrie Brown posted on an Instagram story as the fire still raged. Scores of messages from longtime customers were ecstatic.

But just over a month later, Brown made quite a different announcement: Jimtown Store was closing by year’s end. For good.

Three years of lost income because of wildfires during the autumn grape harvest — peak tourist season in wine country — had proven too much for the small business to handle, Brown said.

Plus, there were the lengthy Pacific Gas & Electric Co. power outages and a lack of affordable nearby housing that has made it “nearly impossible to hire and retain qualified people,” Brown wrote on her website last month.

“It was a great blow to people because they were so greatly relieved that we had been saved” from the Kincade fire, Brown said in an interview. “I knew it was going to come as a major disappointment.”

Jimtown Store closed Dec. 30, with an outdoor party that included plein air painters drawing the store on easels in the parking lot, Champagne toasts and salutary organized bike rides by cyclists who for years had planned long excursions around stops at the cafe.

“I feel that this expression of Jimtown is complete,” said Brown, 64, who has owned Jimtown for 28 years. “It’s a wonderful end to this chapter. I feel good about it. I feel sad for the community, but they shouldn’t be sad for me.”

The Kincade fire burned nearly 78,000 acres in Sonoma County and destroyed 374 structures, 174 of which were homes. While most vineyards survived the blaze, the economic impact of days of closures and canceled events will be felt well into the new year and beyond.

“One of the things that makes Sonoma County so special is the small, family-owned, entrepreneurial nature of many of our businesses. Unfortunately, during the blackouts and the fires, there is definitely an economic impact that is especially hard for these businesses,” Karissa Kruse, president of Sonoma County Winegrowers, an industry group, said in an email.

The region also has been challenged by the state’s affordable housing crisis, making it “hard to attract a workforce,” she said.

“The impact of the fires and blackouts just puts an exclamation point on the issues that have been facing us for the past decade,” she said.

Kruse lost her own Santa Rosa home in the 2017 Tubbs fire. The stress was so much that some of her hair fell out, she said.

Liz Johnson owns Thunderbird Ranch off Highway 128, which hosts events like weddings, family reunions and company picnics. While her buildings survived, the property was damaged by the flames — trees, the deck, the barbecue area — and she was besieged with event cancellations.

“People back away once it hits September, worried that their event will get canceled because of fires,” she said. “I am so much more fortunate than my neighbors who burned to the ground, but we don’t know what we’re going to do because insurance is so delayed with everything. We don’t anticipate much going on in 2020.”

Johnson, who declined to share her age, was born and raised in the Alexander Valley and has been going to Jimtown Store since she was a child tagging along with her grandmother.

When the previous owners called it a day in the early 1980s, she said, it was “such a sad deal for the valley.” Johnson was there the day Brown opened it back up in 1991.

Johnson took her daily breaks from running her own ranch down the street and always came to Jimtown for a cappuccino or perhaps a bowl of potato leek soup.

“Jimtown is the hub of the Alexander Valley,” she said. “It’s where you got all your information, your nice gossip, like who was having a baby and who got married.”

Carlos Perez, who owns Bike Monkey, a Santa Rosa cycling event production company, said bicyclists flocked to Jimtown during long rides on the remote roads of the Alexander Valley, where there aren’t many places to take a break.

So many Spandex-clad cyclists visited Jimtown that Bike Monkey last year bought the store a bigger bike rack, Perez said. It was always full.

“For us, it’s like, oh, my God, we’re losing a place that really was something that enabled us to do these long rides,” Perez said. “It’s more than just the loss of a cool place to stop along the way; it’s the kind of place that gave us a certain capacity to do some incredible rides in Sonoma County.”

On the store’s last day, Perez organized about 50 bicyclists in a ride from downtown Santa Rosa to Jimtown for a final sandwich.

Jimtown Store — and the hamlet that surrounds it — is named after James Patrick, who founded a general store and post office there in the 1890s. While the store itself has been remodeled, the original redwood barn remains, and the historic galvanized metal barn that was once used to sell hay, feed and farm supplies was a party barn in recent years.

When Brown, a Bay Area native, and her late husband John Werner, a former partner in New York’s famed Silver Palate gourmet takeout shop, stumbled onto the abandoned Jimtown Store in 1989, it still had an antique cash register, boxes of old fishing lures stacked on the floor and outhouse toilets.

They spent a year and a half restoring it, envisioning an elegant, modern bistro in a rural setting. They parked a faded red 1955 Ford pickup truck, once used as a country fire truck, out front and put up a sign with a red arrow and the words “GOOD FOOD.”

They published “The Jimtown Store Cookbook,” created a line of condiments and served dishes like Mom’s Potato Salad, Chain Gang Chili, and the Jimtown — a sandwich with prosciutto, blue cheese and olive tapenade on a French baguette.

Brown, who lives in a cottage on the property and is searching for new owners, said Jimtown grappled with problems now persistent throughout the region. If it’s going to be reopened someday, she said, it’s probably going to have to be taken off the grid.

The property’s water is pumped from a well, and “if you don’t have power, you don’t have water,” Brown said. That means no kitchen, no restrooms. The store has to close when the power’s off. Jimtown would need a massive generator to support the refrigerators, heating and multiple stoves, not a “little rinky-dink Home Depot generator,” she said.

“If you’re going to have a business here, it cannot be beholden to PG&E,” she said.

It’s been three years of disaster, she said. Before the Kincade fire, there was the 2017 Tubbs fire in Sonoma County that killed 22 people, then the 2018 Camp fire that obliterated the town of Paradise in Butte County.

Even though the Camp fire was 160 miles northeast, the smoke was so bad at Jimtown that Brown had to cancel multiple outdoor catered events.

In addition to the disasters, the store, which typically employs about 20 people, has been chronically understaffed, she said. She had five college students working there this summer. After they went to off to school, she has not been able to replace them.

“Things have to change in order to make it sustainable,” Brown said. “We have to be smart. We have to figure it out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.